A phantom, a specter, a ghost, a spirit, or what Heidegger termed as “ontological obscurity, (Derrida, p461)” is closely linked with cinema. Seeing flickering moving images projected on the screen, one must connect the question of technicity with that of faith. A phenomenon of belief, of “pretend as if,” is an inherent quality of the narrative film. The spectral dimension is neither the living nor the dead, neither hallucination nor perception. According to Jacques Derrida, “Cinema is the image grafted from the past, a spectral memory, a magnificent mourning. (Baeque, Thierry, and Kamuf, p27)”

It’s that mourning part of Derrida’s discussion that I want to examine and draw the correlations to the idea of phantoms in the capitalist society in which we live in, in three different films, Germany Year 90 Nine zero (Godard), Vagabond (Varda) and Personal Shopper (Assayas). Each director has a vastly different approach to cinema. But they have some common threads running through all their films; changes in society, advancement of technology and its effects and the exploration of cinema/personal history. But moreover, I believe there are sharp critiques of capitalism in these three films and similarities in their calls for the need of spirituality in our society.

A phantom, a specter, a ghost, a spirit, or what Heidegger termed as “ontological obscurity, (Derrida, p461)” is closely linked with cinema. Seeing flickering moving images projected on the screen, one must connect the question of technicity with that of faith. A phenomenon of belief, of “pretend as if,” is an inherent quality of the narrative film. The spectral dimension is neither the living nor the dead, neither hallucination nor perception. According to Jacques Derrida, “Cinema is the image grafted from the past, a spectral memory, a magnificent mourning. (Baeque, Thierry, and Kamuf, p27)”

It’s that mourning part of Derrida’s discussion that I want to examine and draw the correlations to the idea of phantoms in the capitalist society in which we live in, in three different films, Germany Year 90 Nine zero (Godard), Vagabond (Varda) and Personal Shopper (Assayas). Each director has a vastly different approach to cinema. But they have some common threads running through all their films; changes in society, advancement of technology and its effects and the exploration of cinema/personal history. But moreover, I believe there are sharp critiques of capitalism in these three films and similarities in their calls for the need of spirituality in our society.

After his Dziga Vertov Group/political film days and his collaborative period with Anne Marie-Mieville where he exclusively made political documentaries and experimental video works in most of the 70s Godard returned to feature filmmaking with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980). During the 80s and 90s, one striking feature of his style was the presence of nature punctuating the rhythm of his films. I view Godard’s output during this period as more spiritual than his earlier works. Nature is presented, not with characters or weaved into the narrative, but rather used in opposition to, and for criticizing a morally bankrupt, rampant capitalist society. It’s the use of nature that counterbalances capitalism and its effect on people, whether it’s a close up of setting sun or an empty windswept field in Je vous salue Marie (1985), shots of waves rolling into shore in Prenom Carmen (1983), a cloud obscuring the sun or swaying reeds in Nouvelle vague (1990), the sun in a woman’s mouth in Hellas pour moi (1993), or the foggy lakeside in For Ever Mozart (1997).

The first example from this period, and that showcases nature as something divine, is Germany Year 90 Nine zero/Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro (1991), an hour long film made for French TV, with its title mimicking Godard’s idol Roberto Rossellini’s neorealist, post-WWII drama, Germany Year Zero/Germania anno zero (1948). Godard’s take on post-Wall Germany, after the collapse of Soviet Union, shows the onslaught of earth-churning machines and advertisements for material goods.

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero features the return of Lemmy Caution (played once again by Eddie Constantine), from the hard-boiled detective serial, and also featured in his sci-fi film, Alphaville, 25 years prior. Caution walks through the uninhabited fields and marshland of the German countryside as the morning mists roll over them, the existence of god in a voice over when he reaches abandoned church overgrown with vegetation, “This god of nature speaks to us, educates us and gives himself to us. And if we make our beloved into such a divinity, then this is putting religion into practice. (Godard, 1991)”

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero features the return of Lemmy Caution (played once again by Eddie Constantine), from the hard-boiled detective serial, and also featured in his sci-fi film, Alphaville, 25 years prior. Caution walks through the uninhabited fields and marshland of the German countryside as the morning mists roll over them, the existence of god in a voice over when he reaches abandoned church overgrown with vegetation, “This god of nature speaks to us, educates us and gives himself to us. And if we make our beloved into such a divinity, then this is putting religion into practice. (Godard, 1991)”

Lost in time and place, the last ‘secret agent’ has one last assignment; he must travel through Germany on foot, from East to West. We first find Caution living above a hair salon in East Germany under a different name. While there, he is contacted by a former government official whose identity or allegiance is unknown. Caution is ordered to go to the west in a fool’s errand. Godard makes literary references to Cervantes, putting Caution in a Quixotic quest as he narrates in voice-over quoting Rilke, “The dragons in our lives are only princesses who are waiting for us to act with beauty and courage. (Godard, 1991)” It was Caution, who defeated Alpha 60, the supercomputer in charge of the technocratic totalitarian world, with poetry and the irrationality of love in Alphaville. And the dragon turned into Anna Karina.

Godard uses Don Quixote to emphasize the failure of the heroic individual, as if to suggest that there is only so much that individual belief and desire can do to transform the world. Unfettered capitalism is swooping in to fill the vacuum and people are facing the prospects of wage slavery. The spirit of the 68’ was dead. Caution, a fictional character, is the perfect specter, a relic from the past, sleepwalking through now the unified Germany. Unable to change the world like he once thought he did, but only to witness what’s to come from the sidelines, like a ghost from the past.

Caution encounters the same woman he met in the hair salon now working as a maid at a hotel in West Berlin. He tells her, “So you chose the freedom too, eh?” She repeats the same Nazi slogan that adorned the gates of Auschwitz concentration camp, “Arbeit macht frei/Work Makes You Free.” In not-so-subtle terms, Godard reminds us that Germany’s atrocious war past should not be forgotten, and that in the year 1990, almost a half decades after the end of WWII, Germany is still haunted by its past, only this time, the ghosts are not the war deaths, but a different kind of ghosts, the ghost of the capital.

Caution encounters the same woman he met in the hair salon now working as a maid at a hotel in West Berlin. He tells her, “So you chose the freedom too, eh?” She repeats the same Nazi slogan that adorned the gates of Auschwitz concentration camp, “Arbeit macht frei/Work Makes You Free.” In not-so-subtle terms, Godard reminds us that Germany’s atrocious war past should not be forgotten, and that in the year 1990, almost a half decades after the end of WWII, Germany is still haunted by its past, only this time, the ghosts are not the war deaths, but a different kind of ghosts, the ghost of the capital.

If the onslaught of advertisements for material goods and the prospects of wage slavery were haunting the newly united Germany in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero, the same capitalistic inclination is at work in Agnes Varda’s scathing criticism of the developed world, Vagabond. Varda wasn’t didactic in her films. Nor was she brazenly literal in her political point of view like Godard was in his Marxist period. But her criticism of capitalism appears in her 2000 documentary, The Gleaners and I. With its focus on sustainability and its denunciation of colossal food waste, the lovely portrait of the people living in the margins, nevertheless, remains a sharp criticism of the capitalist system.

If the onslaught of advertisements for material goods and the prospects of wage slavery were haunting the newly united Germany in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero, the same capitalistic inclination is at work in Agnes Varda’s scathing criticism of the developed world, Vagabond. Varda wasn’t didactic in her films. Nor was she brazenly literal in her political point of view like Godard was in his Marxist period. But her criticism of capitalism appears in her 2000 documentary, The Gleaners and I. With its focus on sustainability and its denunciation of colossal food waste, the lovely portrait of the people living in the margins, nevertheless, remains a sharp criticism of the capitalist system.

In Vagabond (1985), the free-spirited hippie woman who dies so unceremoniously in the beginning of the film, always struck me as a phantom. She is a manifestation of what the idea of a vagabond is, in various people’s imaginations- an idea of a rebellious free spirit literally conjured up out of the sea, into the minds of cold-hearted citizens of the global economy. Told in documentary style it interviews with the townsfolk of Nîmes (many who were real residents), who encounter Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), Vagabond sketches out the picture of an enigmatic young drifter who comes into town in the middle of winter. There are people who see Mona with sympathetic eyes and those who don’t. There are people who lend her helping hands and those who take advantage of her. There are some who are disappointed by her antics and some who are envious of her freedom. She is an object upon which they can project their wishes, envy and hatred.

In Vagabond (1985), the free-spirited hippie woman who dies so unceremoniously in the beginning of the film, always struck me as a phantom. She is a manifestation of what the idea of a vagabond is, in various people’s imaginations- an idea of a rebellious free spirit literally conjured up out of the sea, into the minds of cold-hearted citizens of the global economy. Told in documentary style it interviews with the townsfolk of Nîmes (many who were real residents), who encounter Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), Vagabond sketches out the picture of an enigmatic young drifter who comes into town in the middle of winter. There are people who see Mona with sympathetic eyes and those who don’t. There are people who lend her helping hands and those who take advantage of her. There are some who are disappointed by her antics and some who are envious of her freedom. She is an object upon which they can project their wishes, envy and hatred. In one scene Mona and her fellow vagrant traveling companion take refuge in a boarded up, abandoned mansion. The sleeping pair is discovered by a maid who imagines a romantic notion of the free souls in love. The sight resembles almost a religious renaissance painting. Just like Godard’s quoting Rilke over divine landscapes, I think this shot represents Varda’s inclinations to bring in the spirituality to otherwise bleak assessment of humanity in a capitalist system where one can die of exposure without people turning heads.

For me, more than anything, Mona’s death is symbolic of the death of the Flower Power generation of the 60s. Born out of the resistance movement against the Vietnam War, they soon became synonymous with the hippie movement, counterculture, and drugs. Even though she was a decade or two older, the movement wasn’t lost on Varda, who experienced it firsthand when she moved to San Francisco in 67’, when her husband Jacques Demy landed a contract with a Hollywood studio. She subsequently made three films in California - Uncle Yanco, Black Panthers and The Lion's Love (...and Lies). “It was a shower of freedom," she recalled in a 2009 interview. “Suddenly, everything was different. It was a peace and love time. They were trying to have sexual revolutions and colors were daring. They were eating different. I had to learn the language and we threw ourselves into the generation and we loved it so much. (King, 2009)” In this sense, Mona in Vagabond was an image grafted from the past, a spectral memory.

For me, more than anything, Mona’s death is symbolic of the death of the Flower Power generation of the 60s. Born out of the resistance movement against the Vietnam War, they soon became synonymous with the hippie movement, counterculture, and drugs. Even though she was a decade or two older, the movement wasn’t lost on Varda, who experienced it firsthand when she moved to San Francisco in 67’, when her husband Jacques Demy landed a contract with a Hollywood studio. She subsequently made three films in California - Uncle Yanco, Black Panthers and The Lion's Love (...and Lies). “It was a shower of freedom," she recalled in a 2009 interview. “Suddenly, everything was different. It was a peace and love time. They were trying to have sexual revolutions and colors were daring. They were eating different. I had to learn the language and we threw ourselves into the generation and we loved it so much. (King, 2009)” In this sense, Mona in Vagabond was an image grafted from the past, a spectral memory. Vagabond is a formal, rigorous work, concentrating more on the tapestry of movement, sound and image and less on character psychology. But the project was born out of Varda’s dismay that people were still dying of exposure in the civilized modern world. Therefore it’s important to examine what was happening in France in the mid 80s’, when the film was made. The robust post-war economy of the last three decades was slowing down. The promises of François Mitterrand and his Socialist government went largely unfulfilled. After the promising start of “regularization” of migrant workers (most of them North Africans from the former French Colonial African nations), due to economic pressure, the friendlier immigration policies were mooted by 1983. There was general discontent and high unemployment. And the height of American economic and cultural hegemony was epitomized by the Euro-Disney breaking its ground in Paris, in 1985. Mona, who manifested out of the sea, like Venus in a renaissance painting, who refused to conform by refusing to be a secretary and dropping out of the grid, had no place in the cold hearted capitalist system in France in the 80s.

Godard and Varda were from the same pre-WWII generation and grouped together as French New Wave, both starting to make films in the 1950s, Olivier Assayas, a post-war generation filmmaker, moved away from the radical politics of the French New Wave of the 60s. He has been in pursuit of something different, something newer. His films divert from conventional narratives. He mixes different genres and thematic tones to reflect our increasingly complicated hyper capitalist society. His films are seen as postmodern, not only because he portrays modern phenomena, such as the internet porn, industrial espionage, and celebrity culture, but he is interested in the friction in storytelling devices, in casting and between satire and reality. He has been the chronicler of hyper capitalist, celebrity addicted society like no other, with Irma Vep (1996), Demonlover (2002), Boarding Gate (2007), Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), Personal Shopper (2016), Nonfiction (2018), Wasp Network (2019), and Irma Vep the TV Series (2022).

A good example of a disorienting yet discernable modern world is portrayed in Demonlover. It’s a formless, lucid fever dream, a corporate espionage intrigue that reflects a borderless, transient world in which the internet, globalization, and corporate mergers and takeovers have obliterated any sense of continuity or personal loyalty. In it, people are endlessly talking in business jargons while backstabbing each other in the confines of private jets, luxury hotel rooms and the antiseptic glass towers of their corporate headquarters. Sex is a commodity and a spectacle in Demonlover. The film is so over the top, convoluted in its narrative, and devoid of humanity, you can’t not think of it as an unfunny parody of the late capitalist system on steroids.

A good example of a disorienting yet discernable modern world is portrayed in Demonlover. It’s a formless, lucid fever dream, a corporate espionage intrigue that reflects a borderless, transient world in which the internet, globalization, and corporate mergers and takeovers have obliterated any sense of continuity or personal loyalty. In it, people are endlessly talking in business jargons while backstabbing each other in the confines of private jets, luxury hotel rooms and the antiseptic glass towers of their corporate headquarters. Sex is a commodity and a spectacle in Demonlover. The film is so over the top, convoluted in its narrative, and devoid of humanity, you can’t not think of it as an unfunny parody of the late capitalist system on steroids. Personal Shopper marks Assayas’s second collaboration with American Actress Kristen Stewart, who at the time was a main subject of tabloid and celebrity gossip. In it, she plays Maureen, a young American woman living in Europe who has a very modern job, shopping for a celebrity who doesn’t have time to do it herself. It’s a fantasy world (yet real) of the rich and famous. And it’s a vacuous world. The job is a concept majority of people can’t relate to, yet know that it exists in our consumerist, celebrity obsessed society. But ironically, with the stroke of genius in casting, it’s the presence of Stewart that provides much needed humanity in the film. Assayas said about Personal Shopper, “I think the film is totally over the top ridiculous about the fashion world or celebrity worshiping culture, but I wouldn’t say I am satirizing them. I am presenting them as reality. That there is that side of the world that actually exists. (Chang, 2016)”

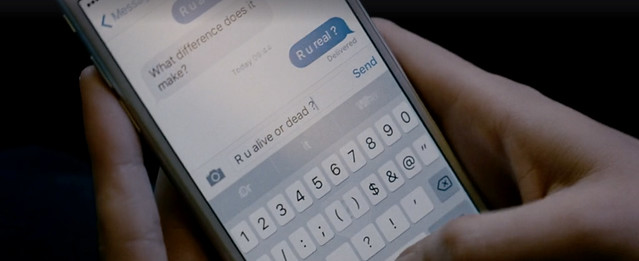

Maureen is also a medium, trying to connect with her twin brother who died suddenly, from a heart condition they both share. She starts getting text messages from someone she doesn’t know. At first, she thinks it’s a sign that her dead brother is making contact with her from the other side. But increasingly, the text messages become more sinister and voyeuristic. Then someone murders her employer and unexplained things start happening; objects move around by themselves, an invisible being detected at an automatic sliding doors and an ectoplasm vomiting translucent being. Is it the creepy ex-boyfriend of her dead employer who is a murderer and texting Maureen? Is he orchestrating the elaborate hoax on her? The film plays out like a thriller with some supernatural elements.

Maureen is also a medium, trying to connect with her twin brother who died suddenly, from a heart condition they both share. She starts getting text messages from someone she doesn’t know. At first, she thinks it’s a sign that her dead brother is making contact with her from the other side. But increasingly, the text messages become more sinister and voyeuristic. Then someone murders her employer and unexplained things start happening; objects move around by themselves, an invisible being detected at an automatic sliding doors and an ectoplasm vomiting translucent being. Is it the creepy ex-boyfriend of her dead employer who is a murderer and texting Maureen? Is he orchestrating the elaborate hoax on her? The film plays out like a thriller with some supernatural elements.

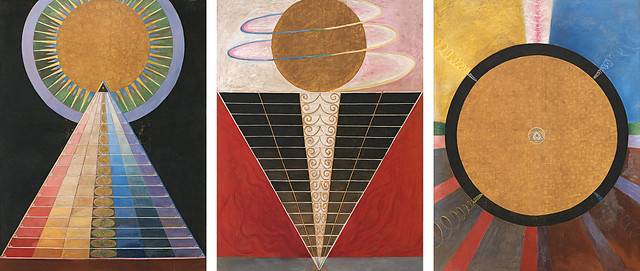

Personal Shopper features Maureen reading about the turn of the century Swedish painter and spiritualist, Hilma af Klint, first on her smartphone and then in a book on the pioneer abstract painter. Klint, after losing her younger sister at a young age, joined a circle of women spiritualists known as “the five” and dedicated herself to connect the spirits of the dead with her abstract art. Again, like Godard and Varda, Assayas uses art to represent spirituality. af Klint’s powerful large scale, colorful paintings counter that of the shallow and decadent world that Assayas presents in Personal Shopper. Maureen is desperate to hold on to something that is missing from her surroundings.

Phantoms in Assayas - Irma Vep and Personal Shopper, are quite literal in cinematic sense. They are fantasy elements from the cinema’s past. Irma Vep draws its inspirations from the character from Feuillade’s silent serials Les Vampires. Personal shopper’s rather shoddy, simple ghost effects resemble spirit photography of the 19th century, and a floating glass cup in mid-air is from House on a Haunted Hill variety.

Phantoms in Assayas - Irma Vep and Personal Shopper, are quite literal in cinematic sense. They are fantasy elements from the cinema’s past. Irma Vep draws its inspirations from the character from Feuillade’s silent serials Les Vampires. Personal shopper’s rather shoddy, simple ghost effects resemble spirit photography of the 19th century, and a floating glass cup in mid-air is from House on a Haunted Hill variety. No films are ever not political political and I see Personal Shopper, however superficial it seems, touching upon a yearning for spirituality in a soulless hyper-capitalist society. Assayas said, “We live in a world that is very materialistic and we all have some sort of spiritual longing. To me it was very much of a portrait of a contemporary character with some universality to her. I went to extremes that her day job was working as a proletarian of the fashion industry. She does a superficial job that she dislikes where she doesn't find satisfaction. There is spiritual longing, trying to connect with an invisible world. (Crummy, 2016)”

In all three of these films, the directors invoke phantoms in three distinctly different ways. Lemmy Caution, a spy whose job is rendered useless in post-wall Germany, is now a tired, incapable old man, a lost spirit, mourning the death of idealism of the 60s, and of the dream of unrealized communist utopia, in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero. Based on a news article about a homeless man being frozen to death, Vagabond finds Mona, an embodiment of the Flower Power generation, whose anti-conformist ideals, dead in a frozen ditch. Maureen desperately hangs on to the idea of an invisible world while living in an absurdly materialistic, superficial world in Personal Shopper.

In all three of these films, the directors invoke phantoms in three distinctly different ways. Lemmy Caution, a spy whose job is rendered useless in post-wall Germany, is now a tired, incapable old man, a lost spirit, mourning the death of idealism of the 60s, and of the dream of unrealized communist utopia, in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero. Based on a news article about a homeless man being frozen to death, Vagabond finds Mona, an embodiment of the Flower Power generation, whose anti-conformist ideals, dead in a frozen ditch. Maureen desperately hangs on to the idea of an invisible world while living in an absurdly materialistic, superficial world in Personal Shopper. With the choking death of Jordan Neely lingering in the news, I can’t help connecting the dots. Times have changed. People were on the road like Mona in Vagabond by choice, not by systematic economic injustices suffered by today’s homeless population. Christian Petzold, a German filmmaker who constantly portrays people on the road in his work, responded to a question about the differences in his characters who are on the road and the characters from the New German cinema of the 70s: “...in the 70s, everyone was rich in West Germany. We thought that we'd won 68' and we thought we could change society…. Films by directors like Wenders- when they (characters) are on the road; they are on the road not because of economic reasons or pressure. They are like Novalis or Hölderlin. They are on the road because they are romantics. (Chang, 2012)”

In the shadow of material wealth brought on by capitalist system in global economy, grew a glaring discontent in those left behind. In Petzold’s films, people are on the road not by their choice, but because of economic situations that made them uprooted and spat out onto the road, left directionless, haunting the world as living ghosts. The accelerations of the wealth gap saw explosions in homeless populations across the US. According to Housing and Urban Development (HUD), 580,000 people experienced homelessness in 2020. According to Gothamist, 1 out of 120 New Yorkers are living in the streets. But the similarities are in the general indifferences on their death. Varda’s deliberate, matter-of-fact presentation of Mona’s death in the beginning of the film is just as inhuman as the news headlines on Neely- “Shocking video shows NYC subway passenger putting unhinged man in deadly chokehold.” (NY Post, 2023) It is equally disturbing that the choking death was filmed by onlookers and posted up on social media. Everyone cheered even for a “good Samaritan” who killed Neely for being loud and asking for food and water by putting Neely on a chokehold for 15 minutes.

The Communist Manifesto starts with “A specter is haunting Europe.” The specter in this case was communism. But idealism lost out to the capital in the end. Maybe the real specter isn’t Lemmy Caution or Mona or some malevolent entity that might or might not be Maureen’s dead brother, but capitalism itself. And the phantoms in these films are mourning the society we are living in. A specter haunting the World.

Bibliography:

Baecque, Antoine de, Jousse, Thierry and Peggy Kamuf. “Cinema and Its Ghosts: An Interview with Jacques Derrida.” Discourse 37, no. 1–2 (2015): 22–39.

Chang, Dustin. “Interview: Olivier Assayas Talks Kristen Stewart and Breaking the Boundaries of Narrative Filmmaking.” Screen Anarchy. March 11, 2017

https://screenanarchy.com/2017/03/interview-olivier-assayas-talks-kristen-stewart-and-breaking the-boundaries-of-narrative-filmmaking.html

Chang, Dustin. “I Envision All These Great Small Movies in the Ruins of Hollywood: Christian Petzold Interview.” Screen Anarchy. December 12, 2012

https://screenanarchy.com/2012/12/i-envision-all-these-great-small-movies-in-the-ruins-of-hollywood-christian-petzold-interview.html

Crummy, Colin. “The Spiritual Inspirations Behind ‘Personal Shopper.’” i-D, March 17, 2017

https://i-d.vice.com/en/article/papy99/the-spiritual-inspirations-behind-personal-shopper

Derrida, Jacques, Geoff Bennington, and Rachel Bowlby. “Of Spirit.” Critical Inquiry 15, no. 2 (1989): 457–74.

Kelly, Alexandra. “HUD says homelessness in the US has exploded, before and during pandemic.” The Hill. March 18, 2021

https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/poverty/543868-hud-says-homelessness-in-us-has-exploded-before-and-during/

King, Susan. “Varda looks back at her life loves.” Los Angeles Times. July 3, 2009

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2009-jul-03-et-agnes3-story.html

Morgan, Daniel. “The place of nature in Godard’s late films.” Critical Quarterly 51. 3 (2009): 1-24.

Stewart. Justin. “Vagabond.” Reverse Shot. October 17, 2016

https://reverseshot.org/archive/entry/2269/vagabond

No comments:

Post a Comment