So one thing I am thankful for this time of worldwide pandemic, where we are witnessing our capitalist society slowly collapsing in real time, is it finally shoved me into watching the whole of Histoir(s)du cinema, Godard's monumental reflection on the 20th century and the role of cinema in it. It's been a long overdue, to say the least. Except for Numero Deux which Godard directed with Anne-Marie Miéville (1975), Histoire(s) is the precursor to all his later essayistic films. Clocking at 266 hours, although divided in 8 parts, it marks the longest among his films.

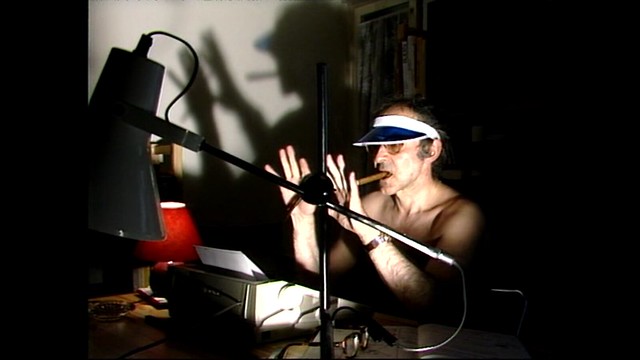

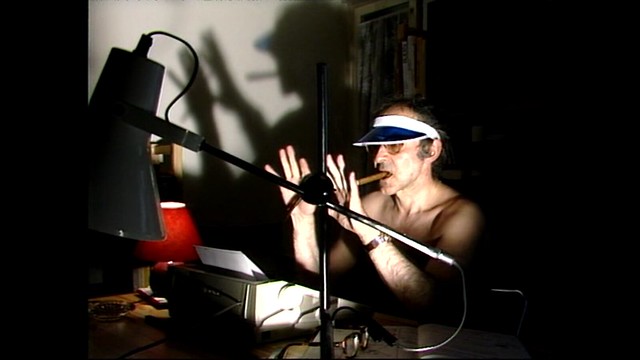

With a cigar permanently fixed in the corner of his mouth, his electric typewriter always roaring its plastic screech in the background and forever blinking images testing us with our persistence of vision, Godard sets out to examine the 20th century riddled with war and destruction and cinema's place within it, or shall we say, our place in cinema. His repetitive themes throughout the whole series is that cinema is neither art nor technique but a mystery. He makes numerous comparison with art and cinema throughout. The difference between film theorist and their books, Godard has been a 'camera-pen' of the auteur theory in practice, churning out these visual essays for almost four decades now.

Godard makes the convincing case with him being a French New Wave filmmaker and how that puts him in unique position to assess cinema history: Belonging to the Post-War generation, seeing enough films through the cinema's evolution and progression. Born out of the idea of image projection by a feverish Napoleonic soldier in Russian prison, Histoire(s) is also the (hi)story of French cinema.

Godard's wordplay never stops. Besides the word histoire in French having two meanings (history and story), he dissects words and constantly rearranges them also. This project being started during the peak of video technology, he points out the implications of its terms - Master/Slave when describing master tape/file and its copies - the term we still refer in film post-productions and information technology. His assertion of the power of image throughout his filmography also hasn't changed - it seems, in Godard's mind, sequential shots of dead bodies in the atrocities of war and pornography reveals the duplicitous nature of cinema.

In Deleuze's Cinema I & II, the philosopher makes a distinction between Movement-Image period and Time-Image period before/After World War II: and how Movement-Image oriented thinking gave rise to nazism and propaganda and ended up in the gas chamber. Time-Image concerns aberration of image and sound. And that more or less starts with Italian Neorealism which precedes French New Wave. Partly because they didn't have any reference point with total destruction of their surroundings, they had to think seeing images differently with sound as an independent partner, not just dialogue track. Obviously well-read, Godard knows this, and praises the films of de Sica, Antonioni and Pasolini because Italian filmmakers, with its long illustrated history and language, didn't remain silent during the war years (1941-45) and right after. In Cinema II, Deleuze also makes a point of the power of false; falseness in image, just as impactful but also dangerous. Godard says cinema is not entertainment nor communication device but rather cosmetics, a small industry of lies.

Balkan War in the 90s really affected Godard and its continuation and repetition of atrocities since the war affirmed his cynicism toward humanity greatly and it show in the later part of Histoire(s). He continues to revisit the notion of 'newness of history' and 'history of news'. In the time of fake news, how do we see through all these falseness and dig out the truth? Godard seems to admit that we live in a corrupt state, but like poetry and art, cinema can see us through. And I really hope this is the case.

With a cigar permanently fixed in the corner of his mouth, his electric typewriter always roaring its plastic screech in the background and forever blinking images testing us with our persistence of vision, Godard sets out to examine the 20th century riddled with war and destruction and cinema's place within it, or shall we say, our place in cinema. His repetitive themes throughout the whole series is that cinema is neither art nor technique but a mystery. He makes numerous comparison with art and cinema throughout. The difference between film theorist and their books, Godard has been a 'camera-pen' of the auteur theory in practice, churning out these visual essays for almost four decades now.

Godard makes the convincing case with him being a French New Wave filmmaker and how that puts him in unique position to assess cinema history: Belonging to the Post-War generation, seeing enough films through the cinema's evolution and progression. Born out of the idea of image projection by a feverish Napoleonic soldier in Russian prison, Histoire(s) is also the (hi)story of French cinema.

Godard's wordplay never stops. Besides the word histoire in French having two meanings (history and story), he dissects words and constantly rearranges them also. This project being started during the peak of video technology, he points out the implications of its terms - Master/Slave when describing master tape/file and its copies - the term we still refer in film post-productions and information technology. His assertion of the power of image throughout his filmography also hasn't changed - it seems, in Godard's mind, sequential shots of dead bodies in the atrocities of war and pornography reveals the duplicitous nature of cinema.

In Deleuze's Cinema I & II, the philosopher makes a distinction between Movement-Image period and Time-Image period before/After World War II: and how Movement-Image oriented thinking gave rise to nazism and propaganda and ended up in the gas chamber. Time-Image concerns aberration of image and sound. And that more or less starts with Italian Neorealism which precedes French New Wave. Partly because they didn't have any reference point with total destruction of their surroundings, they had to think seeing images differently with sound as an independent partner, not just dialogue track. Obviously well-read, Godard knows this, and praises the films of de Sica, Antonioni and Pasolini because Italian filmmakers, with its long illustrated history and language, didn't remain silent during the war years (1941-45) and right after. In Cinema II, Deleuze also makes a point of the power of false; falseness in image, just as impactful but also dangerous. Godard says cinema is not entertainment nor communication device but rather cosmetics, a small industry of lies.

Balkan War in the 90s really affected Godard and its continuation and repetition of atrocities since the war affirmed his cynicism toward humanity greatly and it show in the later part of Histoire(s). He continues to revisit the notion of 'newness of history' and 'history of news'. In the time of fake news, how do we see through all these falseness and dig out the truth? Godard seems to admit that we live in a corrupt state, but like poetry and art, cinema can see us through. And I really hope this is the case.

No comments:

Post a Comment