Again, Art of the Real is an immensely rewarding cinematic experience both in form and content. Don't miss it!

Art of the Real runs from April 26 through May 6, 2018 at Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York. Please visit FGSC for more info.

Here is preview of six notable films for your pleasure:

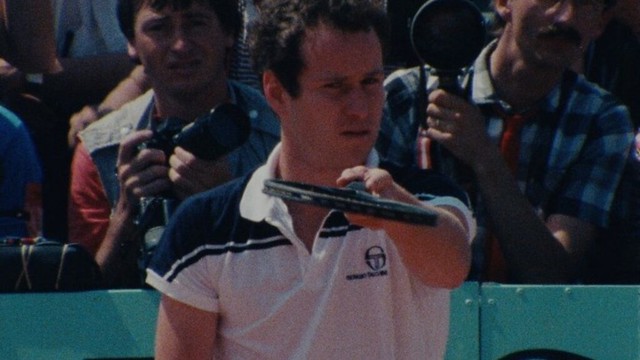

John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection *Opening Night Film

This terrific, archival footage documentary starts with a Godard quote - "Cinema Lies, Sport Doesn't." A French archivist Julien Faraut stumbled upon hours and hours of 16mm shot French Open matches at Roland Garros, initiated by Gil de Kermadec, the first director of French Tennis Federation, to study and make instruction films for aspiring athletes. But what Faraut saw was a compelling, verité style portraits of each players, and especially of McEnroe, who was at the time, the number one player in the world.

It happens that McEnroe wasn't a good model as an athlete who had atypical style for these often rigid, dry instructional films. His form was unusual and his methods were unpredictable, which gave his opponents a hard time. As a perfectionist of the game, he hated incompetency of people in the court and as a result, we've got to know him as who shouted and argued with umpires endlessly. He also hated being filmed or photographed. There are several moments where he stops the game to complain that the rolling cameras were bothering him while looking straight into camera.

Like last year's Dawson City: Frozen Time which uncovered the intersection of Gold Rush and cinema, In the Realm of Perfection finds the intersection of sport and cinema. Drolly narrated by Mathieu Amalric, Faraut creates Chris Marker style film that is both entertaining (thanks largely to McEnroe being himself) and thoughtful. The epic match between McEnroe and his long time nemesis Ivan Lendl in 1984 captured in grainy 16mm is literally, epic.

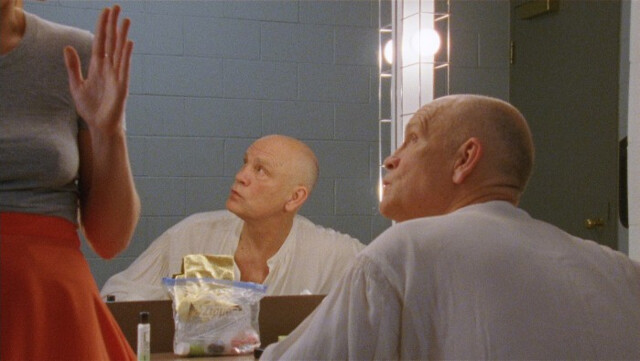

Casanova Gene

German filmmaker Louise Donschen examines desire of all forms in Casanova Gene and it's a fascinating one. In evolutionary biology studying finches in a science lab in the woods, an ornithologist tells us why female finches cheat on their partners - they inherited the Casanova gene from their fathers, as male finches are polygamous. "Is it beneficial to female finches?" the filmmaker asks off the frame and the ornithologist doesn't have an answer. John Malkovich plays Casanova or Malkovich the actor playing one, as he is interviewed by the filmmaker. He simply describes himself as a slave to his senses and explains the difference between character and temperament.

Carnival in Venice is juxtaposed with a church and the clergymen. Kids play in the forest, lights change, illuminating the rooms through the window, a dominatrix in SM studio holds a session, a hypnosis takes a place where a woman experiences intense orgasm. Then there is staged bar scene where transman complains that he misses uterus.

The colors - the red of the roses, orange beak of the finches, grey and red of the clothes- everything surreptitiously intermingles in this seemingly fragmented, yet arresting film that reminds me of the work of Alexander Kluge. A real gem.

Infinite Football

Romanian helmer Corneliu Porumboiu (Police Adjective, 12:08 East of Bucharest) makes a wacky yet poignant documentary about his childhood friend Laurentiu Ginghina, a middle aged bureaucrat who is obsessed with changing the rules of soccer to make the sport safer. At 19, he fractured his right fibula as many players in the opposite team ganged up on him in the corner when he had the ball. Because of the injury, he had to give up hope of going professional. Now he is hell-bent on changing the game - he wants to implement octagonal shaped soccer field with sectioned groups where 5 offensive and 5 defensive players can't cross each other's lines and no offsides. He says this improvement will speed up the game and make it smoother and safer.

He wanted to go to Forestry university but it required physical where you had to run which he couldn't do with his leg. His dream of coming to the US twice - first to run the ranch out in the West, then in Florida, gets thwarted by 9/11 and its aftermath with tighter restrictions. He ended up where he is, some desk job which is not that exciting. Ginghina's sad sap story, told in his office where he keeps getting interrupted with his daily tasks- an old lady with her inheritance questions, paperwork, meetings and appearances, brings out chuckles rather than sympathy.

Porumboiu prods his friend's obsession about 'the ball being free' in a sport where beauty is in player's skills and the ball is just an object. Our bureaucrat obviously is self aware, that deep down he equates himself with the ball and trying to escape from tight corners. That he sees himself as a superhero from comic books, like Superman or Spiderman who has a normal boring dayjob. Is his situation a stand-in for the general disillusionment with European Union, felt by majority of its members? Maybe.

After seeing his plan implemented on the indoor soccer field to not so enthusiastic results, he keeps changing his rules and therefore his creation being tagged as Infinite Football by Porumboiu. The film ends with Ginghina's poignant and touching monologue about the world where there is less violence which the director equates for political utopia. There is no fast zoom in/freeze frame or zany music for cheap laughs. Nor the film intentionally demeans our silly bureaucrat. Just like other Romanian new wave compatriots, Porumboiu knows how to justly reflect the lives of ordinary Romanians finding themselves riding along in a rapidly changing world and facing mildly amusing situations.

Braguino

A French visual artist and film director, Clément Cogitore whose supernatural tinged Afgan war thriller, Neither Heaven Nor Earth, made waves at the film scene few years back, travels to remote Eastern Siberia to document the Braguinos, a family living off the environment. The head of the family tells us that they wanted to get away from it all, so they just packed up and left on their boat. Their 6 children were all born in the taiga. It is clear that the Braguino clan is not only dealing with family rivalry with the neighboring Kilins just other side of the river, but dangerous animals - especially bears and also ever expanding human presence in the region.

Cogitore and his cinematographer Sylvain Verdet is there to capture what can only be described as Tarkovsky-an beauty in rather dream-like Siberian taiga. The natural beauty is only accentuated by fair-haired Braguino children in their colorful dresses and clothes. As the helicopters full of heavily equipped newcomers landing on their territory, we all know that the happy days of the Braguinos are numbered. It's a striking non-fiction filmmaking featuring otherworldly beauty.

Milford Graves Full Mantis

Milford Graves, a free-jazz percussionist, records his heartbeat with a self-made EKG machine hooked up to the computer and makes electronic melodies out of it. He is also a martial art enthusiast and practitioner- he learned his moves through studying preying mantis instead of going to a local dojo. His style is Yara, a yerba word for 'Nimble', a mixture of West African dance moves and martial arts. In the labyrinth of books, machines, instruments, artifacts of his house/studio in sunny South Jamaica in Queens, Graves reminds you of your eccentric uncle- a smart person with full of self-taught knowledge who forms a philosophy of life with first-hand experience. And when he plays, it's electrifying.

Relying completely on Graves' words, Jake Meginsky and Neil Young creates a compelling portrait of a modern day sage and a fantastic storyteller who is approachable and very down to earth. As he talks about his music being the conduit of vibrations of cosmos, you listen. He might be the remnants of 60s mind-body-spirit mumbo jumbo, but the way he is so in tune with nature, as he does gardening in his back yard, as he in tune with his body- his world view makes sense, especially now, when the whole world seems to have gone crazy.

All That Passes Through a Window That Doesn't Open

Martin DiCicco's film charts transcaucasian trail on two side of tracks - Azerbaijan and Armenia. Once a vibrant railway system linking Turkey - Georgia - Armenia and Azerbaijan which served as the crossroads of Eastern Europe and West Asia left in ruins by decades of neglect and regional conflict. Without saying much of its very complicated geo-political history, DiCicco elegantly concocts tale of two countries, one with full of hope and looking forward, the other reeling from the ghost of the past.

In the first 2/3rd, it concentrates on Azerbaijani side, where mostly young migrant workers living on the train cars while they travel to upgrade the railways. Voices of some of its workers narrates their days on the rails, how it's lulling affects their bodies own senses and memories. One says he likes railway works because it's measurable against time. That there's sense of accomplishment as he and his co-workers go closer to their destination. There's dancing, drinking and sense of camaraderie and dangers of accidents too.

After the war between two countries and neighboring Turkey supporting the muslim Azerbaijan and closing off its borders in 1993, Armenian side of the tracks which was a lifeline for trade to the west and east, left to rot. The last 1/3rd of the film features an Armenian station agent guarding the one such neglected station, waiting for it to be open again. His words and accompanying visuals are poignantly drawn out.

All That Passes Through... invokes the poignancy of Kiarostami's road films in contemplating on the time passing. DiCicco and his editor Iva Radivojevic draw a evocative picture of the region full of history, longing and hope.

No comments:

Post a Comment