This is my collection of ever growing Godard viewing log in order of my preferences:

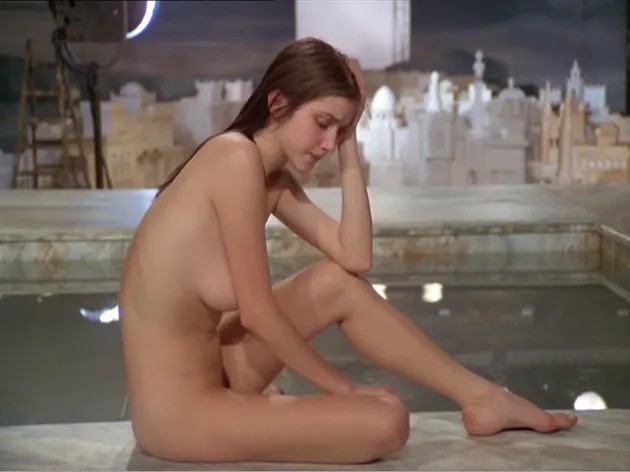

Je Vous Salue, Marie/Hail Mary (1985) - Godard

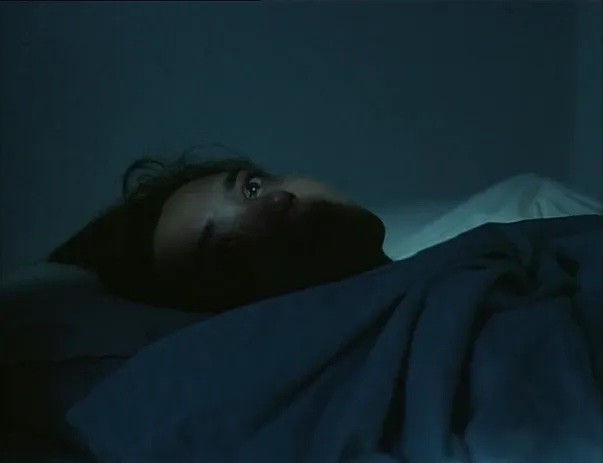

Godard's take on Virgin Mary might have been seen as an assault on Christianity and the idea of Immaculate Conception but it's actually about one of his usual themes- body/soul dichotomy. What's refreshing about Hail Mary is it's also about relationship between two young people being tested: can they love one another without touching? I can see the film's influence on many younger filmmakers whom I once religiously followed, namely Leos Carax and Hal Hartley with their brooding anti-heroic archetypes.

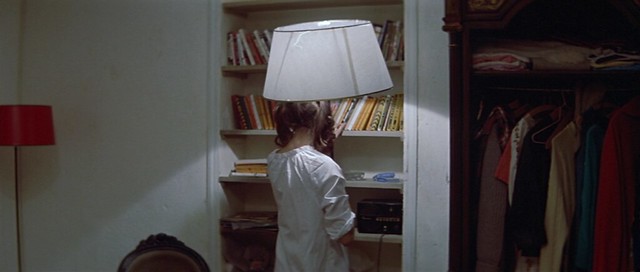

Hail Mary is perhaps the most beautiful color film I've ever seen. Punctuated by amazingly graceful nature photography and anchored by Myriem Roussel's Marie, a high school basketball player and a virgin who finds herself being pregnant. Marie's questioning "what is flesh alone...?" and her struggle to keep herself chaste is touching and deeply felt. It's the presence of Roussel that differentiates Hail Mary from Godard's post-Anna Karina cynicism.

From what I hear, Hail Mary is one of the last films before Godard turned his direction toward visual essays of the 90s which I find dry and uninteresting. Call me old fashioned, but for me ideas are still best conveyed through stories and characters, not in the lecture halls(movie theaters) that Godard still seems to preside over. Cinematically no one can top Godard's playfulness in the 60s, not even Godard himself. But this is a gorgeous stuff. Easily a top ten material for me.

Nouvelle Vague (1990) - Godard

Could Nouvelle Vague be perhaps the most romantic and hopeful Godard film I've seen so far? With stunning visuals and constant, beautiful soundtrack, this new new wave tells a love story between Elena, a rich industrialist (Domiziana Giodarno) and Roger/Richard, a bum (Alain Delon), whom she picks up in her red sports car on the side of the road. She offers him a helping hand. This theme repeats throughout the film. At first, Roger is a quiet fellow and a confused fool who is buried in the background of a giant mansion by the lake filled with the crowd of business people who mostly converse in quotes and business jargons. This scruffy sage becomes an anchor of Elena's hectic life. But when they go boating, Roger falls in the water and Elena refuses to help him. He drowns and comes back as Richard- a business genius overseeing acquiring Warner Bros. Now it's Elena who needs to be saved.

Nouvelle Vague concerns many of Godard's usual themes: masters and servants, rich and poor, dualism, etc. Beautifully realized and impeccably put together (with the forever autumnal Switzerland countryside background and a constant, beautiful soundtrack), the film boasts a lot of stunning images, even for Godard's standard. The rebirth aspect of the film has multiple meanings here- paralleling lives, positive and negative making a whole, repetition of the waves (hence the apt title, not only referring to French New Wave Godard started in the sixties), resurrection of an old icon (Delon, his sharp features and beauty dulled by age), and perhaps the renewal of the First World in the last decade of the century, letting go of its ugly past and prejudices, lending a hand to the world in turmoil. Nouvelle Vague is an engrossing film and certainly is one of the most beautiful Godard films.

*Just found this article about Nouvelle Vague Soundtrack. The soundtrack itself (entire film- sound, dialog in two discs), is put out by ECM. It's a magnificent record.

Click here for the article

Visit ECM Records for ordering CD

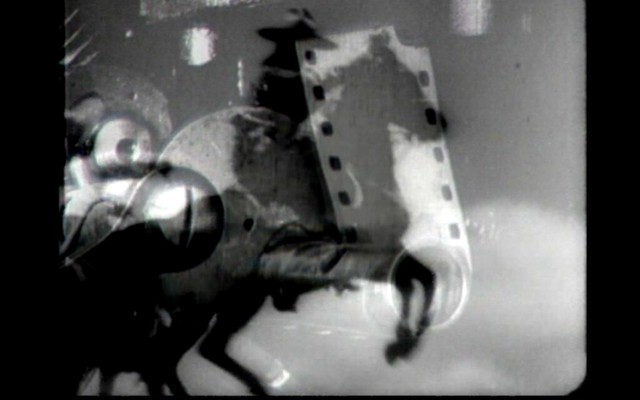

Histoire(s) du cinema (1988-98) - Godard

So one thing I am thankful for this time of world wide pandemic, where we are witnessing our capitalist society slowly collapsing in real time, is it finally shoved me into watching the whole of Histoir(s)du cinema, Godard's monumental reflection on the 20th century and the role of cinema in it. It's been a long overdue, to say the least. Except for Numero Deux which Godard directed with Anne-Marie Miéville (1975), Histoire(s) is the precursor to all his later essayistic films. Clocking at 266 hours, although divided in 8 parts, it marks the longest among his films.

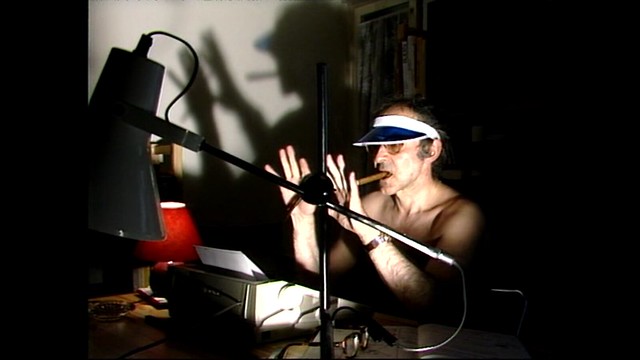

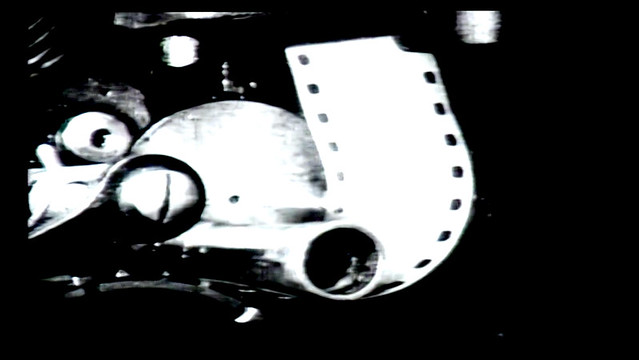

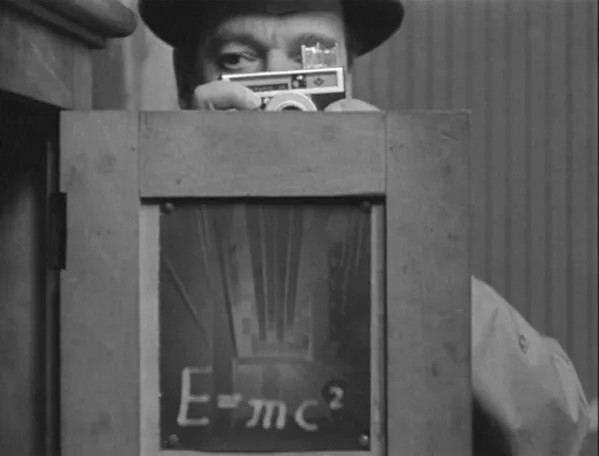

With a cigar permanently fixed in the corner of his mouth, his electric typewriter always roaring its plastic screech in the background and forever blinking images testing us with our persistence of vision, Godard sets out to examine the 20th century riddled with war and destruction and cinema's place within it, or shall we say, our place in cinema. His repetitive themes throughout the whole series is that cinema is neither art nor technique but a mystery. He makes numerous comparison with art and cinema throughout. The difference between film theorist and their books, Godard has been a 'camera-pen' of the auteur theory in practice, churning out these visual essays for almost four decades now.

Godard makes the convincing case with him being a French New Wave filmmaker and how that puts him in unique position to assess cinema history: Belonging to the Post-War generation, seeing enough films through the cinema's evolution and progression. Born out of the idea of image projection by a feverish Napoleonic soldier in Russian prison, Histoire(s) is also the (hi)story of French cinema.

Godard's wordplay never stops. Besides the word histoire in French having two meanings (history and story), he dissects words and constantly rearranges them also. This project being started during the peak of video technology, he points out the implications of its terms - Master/Slave when describing master tape/file and its copies - the term we still refer in film post-productions and information technology. His assertion of the power of image throughout his filmography also hasn't changed - it seems, in Godard's mind, sequential shots of dead bodies in the atrocities of war and pornography reveals the duplicitous nature of cinema.

In Deleuze's Cinema I & II, the philosopher makes a distinction between Movement-Image period and Time-Image period before/After World War II: and how Movement-Image oriented thinking gave rise to Nazism and propaganda and ended up in the gas chamber. Time-Image concerns aberration of image and sound. And that more or less starts with Italian Neorealism which precedes French New Wave. Obviously well-read, Godard knows this, he praises the films of de Sica, Antonioni and Pasolini because Italian filmmakers, with its long illustrated history and language, didn't remain silent during the war years (1941-45) and right after. Deleuze also makes a point of the power of false; falseness in image, just as impactful but also dangerous. Godard says cinema is not entertainment nor communication device but rather cosmetics, a small industry of lies.

Balkan War in the 90s really affected Godard and its continuation and repetition of atrocities since the war affirmed his cynicism toward humanity greatly and it show in the later part of Histoire(s). He continues to revisit the notion of 'newness of history' and 'history of news'. In the time of fake news, how do we see through all these falseness and dig out the truth? Godard seems to admit that we live in a corrupt state, but like poetry and art, cinema can see us through. And I really hope this is the case.

Notre Musique/Our Music (2004) - Godard

Part essay, part narrative, part lecture, this short elegy to Europe is perhaps the most definitive culmination of all Godard's work I've seen so far. Taking cues from Dante's Divine Comedy, the film is in 3 parts: Hell, Purgatory and Paradise (first and last parts are 10 minutes or so and Purgatory is the longest and the meat of the film).

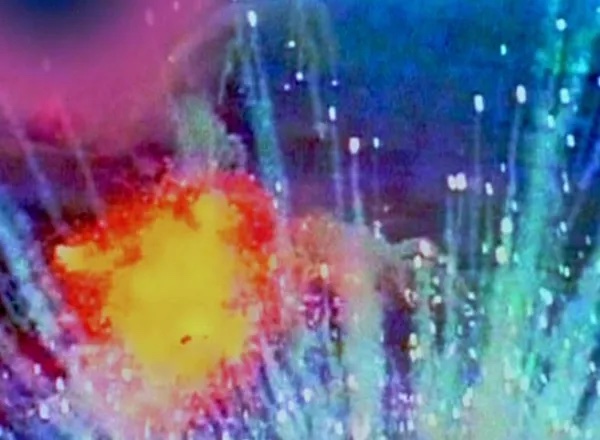

The first ten minutes is rapidly cut reels of horrors of war- both real and imagined (clips from Hollywood movies) and in both black & White and color. Colors are wildly distorted into almost an abstraction.

Set in bullet riddled Sarajevo in winter, Purgatory mainly concerns the Israeli/Palestine conflict. Judith Lerner (Sarah Adler), a journalist from Tel Aviv is in town for a literary conference where Godard (as himself) is set to give a lecture on image/text relationship. Like a tourist in a new city, Judith is constantly visible taking pictures in the war-torn but now reviving city. While interviewing and talking to many people- a Palestinian poet, Spanish architect and so on, who appear as themselves, she is there to be assured/bare witness to, that a reconciliation is possible between bitter enemies somewhere, that the bridge (the famed Mostar bridge, built by the Ottomans in the 15th century and had been standing the test of time until was destroyed in the Bosnian War) can be rebuilt.

Then there is Olga Brodsky (Nade Dieu), a Russian Jew, planning to off herself in a sensational manner in the name of peace. In the Paradise part of the film, Olga walks through the green forest and ends up in water's edge where it is heavily guarded by American GIs.

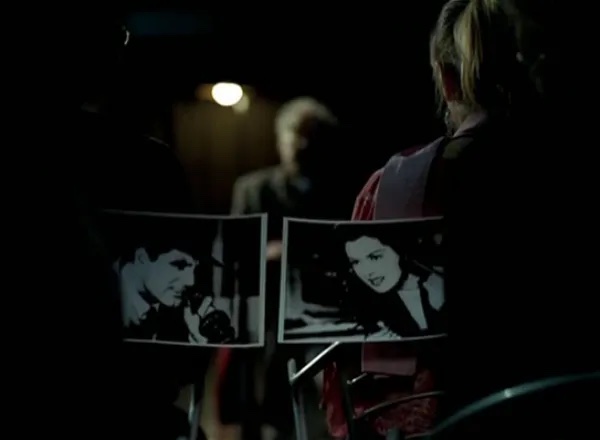

Godard plays with complex ideas through series of images and sound. The film devotes considerable amount of time to Godard's lecture on misinterpretation of images. There is light then there is dark. There is a shot, then there is a reverse shot. As usual, this dichotomic world view that has been consistent throughout his career is pronounced. Similar images can contrast each other side by side but an image without context can be misleading.

The two women- Judith and Olga (both rather plain looking and not particularly noticeable) are mirroring each other. So are damaged, faded fresco of Saint Mary and Olga. The most devastating/hopeful image in Notre Musique is not of a pile of dead bodies or Mostar but close up of Olga's face at the end.

I have to admit that seeing a Godard film requires a bit of effort and get-used-to (visually, since he is not going to give you traditional looking beauty shots). Sometimes his usual heavy Euro-centric references get in the way of viewing. It also feels like a visual literacy class, albeit an exciting one.

Notre Musique is a serious film. His image association games don't feel like tricks. Gone are his youthful glee and silly satiric humor that has been generally perceived as reductive and contradictory, that alienated many filmgoers over the years. The film doesn't give the audience any easy answers. Godard merely suggests that there are things that need to be investigated further: what you can see is not necessarily the truth. Then I realized that Godard has always been paying the highest respect to the audience- to think for themselves. It's also the most non-combative and relatively easy-to-digest Godard film I've encountered so far. Also it's thrilling.

Only misstep (if I call it that) I consider is the appearance of American Indians. The idea of imperialistic America is pretty well pronounced throughout all JLG films. But I find the inclusion of them in the streets of Sarajevo a little more than distracting. Sure they are underrepresented and their stories seldom told. But it feels like harkening back to his old silly self in otherwise somber film.

Élogie de l'amour/In Praise of Love (2001) - Godard

Termed as Godard's third-first film (after Breathless and Sauve qui peut (la vie)), Élogie de l'amour/Ode to Love is an unusually elegant film for his standard. The structure is pretty lean - first hour or so is shot on crisp monochrome 35mm film, the rest is shot on high contrast, saturated video. First part takes place two years after the second. But unlike some of his other films, he avoids his usual diptych sermons. It does concern the usual Godard themes - memories, representation of memories, American hegemony, the war and love. But the film is much more sophisticated and measured than that.

The first part follows a good looking young director Edgar (Bruno Putzulu) as he tries to get things moving on his film about childhood, adulthood and twilight years. He is talking to his art dealer financier M. Forlani and tirelessly pursuing a woman (Cécile Camp) whom he met two years earlier, to star in his film. She in turn refuses repeatedly.

The second part of Élogie concerns largely on Godard's preoccupation with Spielberg's Schindler's List and its representation of Holocaust. His disdain for American culture dominance worldwide hasn't really been a secret, but Schindler's List was such a clutch for him to expound on his hatred fully. There are a pair of arrogant American producers buying off the rights to two old former WWII resistance fighters' stories. The script will be written by a famous American writer (William Styron) and there will be scenes of their younger nude bodies rolling together. But in order to save the historic hotel they own, the old couple cash the check given by Americans in two days.

Love is an interesting subject for Godard since he never dealt with it realistically in his films. It's almost an uncharted territory for him. But I was taken aback by his presentation. It is done so naturally and tenderly without his usual cynicism. The glimpse of the woman's smile on the phone and tender exchanges are the extent of the love story Godard provides- there are no shot/reverse shot for this scene. We only hear one side of the conversation (hers). The woman in question, the grand daughter of the resistance fighters, who later commits suicide, is never fully shown.

Godard's video images are out of this world. It seems Élogie is the culmination of all his interests and obsessions over the years - video technology, Anne-Marie Mieville's influence, Kosovo, the notion of adulthood or lack there of, etc. It's heady, quotation heavy, and spectacularly beautiful.

Helping Hands in Godard's Films: Pierrot le fou

One can argue that human hands represent progress, creativity, guidance, assistance, also destruction and violence. It is then no surprise that hands are a recurring motif in the works of Jean-Luc Godard, one of the key figures of French New Wave, championed the Auteur Theory and who, for the last six decades, labored over making connections between art and life. The connection between the act of creating and the presence of hands has always been present in Godard’s filmography. They represent both a sole authorial voice and steady companionship in many of his late period films. Alexandre Astruc’s article, The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Camera-Stylo, was a basis in defining French New Wave and The Auteur Theory a decade later. In it, Astruc advocates that film directors have the same authorial voice in much the same way that writers would write with a real pen; it was in other words, a call for a new kind of cinema, in which the vision of the ‘author’ – or auteur of the film was central. (Martin 2013). The recurring motif is in many of his 80s and 90s films and most prominently in his epic Histoire(s) du Cinema. What I am trying to suggest here with this article is that not only the act of writing, signifying the authorship is shown but helping hands and companionship, or lack thereof, through hands were presented as early as (if not earlier), in Pierrot le Fou.

One can argue that human hands represent progress, creativity, guidance, assistance, also destruction and violence. It is then no surprise that hands are a recurring motif in the works of Jean-Luc Godard, one of the key figures of French New Wave, championed the Auteur Theory and who, for the last six decades, labored over making connections between art and life. The connection between the act of creating and the presence of hands has always been present in Godard’s filmography. They represent both a sole authorial voice and steady companionship in many of his late period films. Alexandre Astruc’s article, The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Camera-Stylo, was a basis in defining French New Wave and The Auteur Theory a decade later. In it, Astruc advocates that film directors have the same authorial voice in much the same way that writers would write with a real pen; it was in other words, a call for a new kind of cinema, in which the vision of the ‘author’ – or auteur of the film was central. (Martin 2013). The recurring motif is in many of his 80s and 90s films and most prominently in his epic Histoire(s) du Cinema. What I am trying to suggest here with this article is that not only the act of writing, signifying the authorship is shown but helping hands and companionship, or lack thereof, through hands were presented as early as (if not earlier), in Pierrot le Fou.

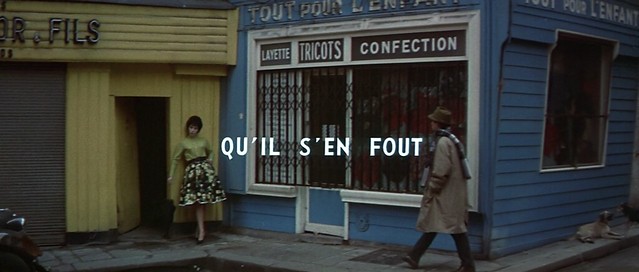

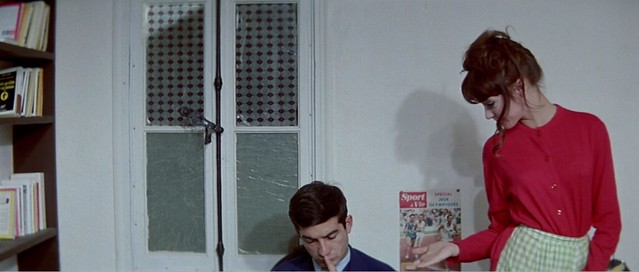

Pierrot le Fou was Godard’s tenth feature, shot in Techniscope for widescreen presentation, based on a crime novel Obsession by Lionel White. It is a road movie with a political intrigue, starring Anna Karina and Jean-Paul Belmondo. Godard had established himself as a formidable director by then, having a string of successes after Breathless; A Woman is a Woman, Vivre sa vie, Contempt, Band of Outsiders, etc. No doubt the success was due, in large part, to Karina’s on-screen presence. But their real-life relationship was tumultuous, and their marriage was dissolved after 5 years in 1965, with Pierrot being their first and last post-divorce era collaboration. Things were dicey in France during and after the Algerian War, 1954 - 1962. Even the north African country won its independence from France through armed struggle. Both in France and abroad, OAS, the extreme Right Wing militant group, carried out a series of violent attacks against those who advocated Algerian independence. The Vietnam War was still raging, and national protest was mounting, and all these sentiments would accumulate to May 68’ three years later. American culture and material goods were flooding in. So were sense disillusionment and escapism in rapidly changing society. This climate is all presented in Pierrot.

The story concerns Ferdinand (Belmondo) who flees his Parisian bourgeois family life with his former lover and family’s sometime babysitter Marianne (Karina), who has ties with dangerous illegal arms dealers. After finding a corpse with scissors stuck in his neck in Marianne’s apartment, the pair escape armed OAS goons and head for the south in the dead man’s car. After a crime spree and ditching two cars- one burned and the other willfully plunged into the water, they settle themselves on an island for simpler life. But the couple soon find out that they are very different from each other - while Ferdinand/Pierrot buries himself in books and writing, Marianne gets bored and longs for civilization and consumerist comforts. After getting caught by the criminals and tortured, they are separated. They find each other again at a marina in Toulon where Ferdinand works as a cabin boy for a woman who claims to be a Lebanese princess in exile. Marianne convinces him to swindle a briefcase full of cash and promises to run away with him afterwards. But she double crosses him with her real boyfriend gunrunner Fred and sails to an island where Fred has a mansion. Ferdinand/Pierrot pursues them and shoots them down. He then paints his face blue and wraps red and yellow dynamite around his head and blows himself up.

The story concerns Ferdinand (Belmondo) who flees his Parisian bourgeois family life with his former lover and family’s sometime babysitter Marianne (Karina), who has ties with dangerous illegal arms dealers. After finding a corpse with scissors stuck in his neck in Marianne’s apartment, the pair escape armed OAS goons and head for the south in the dead man’s car. After a crime spree and ditching two cars- one burned and the other willfully plunged into the water, they settle themselves on an island for simpler life. But the couple soon find out that they are very different from each other - while Ferdinand/Pierrot buries himself in books and writing, Marianne gets bored and longs for civilization and consumerist comforts. After getting caught by the criminals and tortured, they are separated. They find each other again at a marina in Toulon where Ferdinand works as a cabin boy for a woman who claims to be a Lebanese princess in exile. Marianne convinces him to swindle a briefcase full of cash and promises to run away with him afterwards. But she double crosses him with her real boyfriend gunrunner Fred and sails to an island where Fred has a mansion. Ferdinand/Pierrot pursues them and shoots them down. He then paints his face blue and wraps red and yellow dynamite around his head and blows himself up.

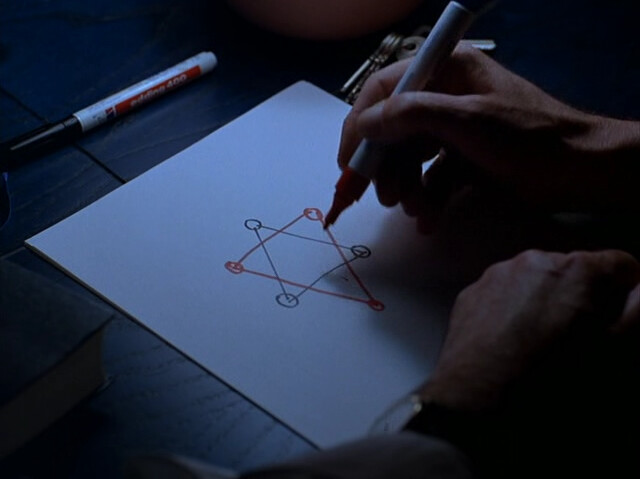

I found a referential detour in Pierrot le Fou in two places. The film shows Ferdinand keeping a journal and constantly writing on graph paper. The act of writing is not new to Godard films; as early as Une Femme Coquette, his first fiction short from 1955 and Karina composing a letter in Vivre sa vie are examples. In Pierrot, it’s his own cursive being written in that journal. Godard’s monumental epic on history and story of cinema, Histoire(s) du Cinema is also ripe with visual motifs of hands. It starts with Godard furiously typing away on his electronic typewriter with that unmistakable screeching of an electronic machine from the 80s. Godard snarls in his throaty voice, “Man’s true condition: to think with hands,” borrowing from the Swiss writer Denis de Rougemont. (Vishnevetsky 2018) The presence of hands particularly stands out in those embodiments of his thoughts, because the essay film is practically a filmed writing process. (Kim 2018)

I found a referential detour in Pierrot le Fou in two places. The film shows Ferdinand keeping a journal and constantly writing on graph paper. The act of writing is not new to Godard films; as early as Une Femme Coquette, his first fiction short from 1955 and Karina composing a letter in Vivre sa vie are examples. In Pierrot, it’s his own cursive being written in that journal. Godard’s monumental epic on history and story of cinema, Histoire(s) du Cinema is also ripe with visual motifs of hands. It starts with Godard furiously typing away on his electronic typewriter with that unmistakable screeching of an electronic machine from the 80s. Godard snarls in his throaty voice, “Man’s true condition: to think with hands,” borrowing from the Swiss writer Denis de Rougemont. (Vishnevetsky 2018) The presence of hands particularly stands out in those embodiments of his thoughts, because the essay film is practically a filmed writing process. (Kim 2018)

About two-third way into Pierrot, the second detour to hands appears with Raymond Devos, a well-known comedian of that time period, who plays a nostalgic man striking up a conversation with Ferdinand/Pierrot at the dock, a place where betrayed Ferdinand/Pierrot embarks for his revenge. The man proceeds to tell a long and convoluted story, with wild gesticulations, about his lost loves. He says he hears music in his head all the time and keeps asking Ferdinand if he hears it too. “Est-que vous m’aimez…?” He keeps singing the song and we hear the music that is in his head, identifying with the man. He says he was wooing a woman by holding and stroking her hand. The story goes that he asked if she loved him, and she said no. The second woman said yes but he didn’t. The third woman said yes, and he held on to her hand for ten years. “You don’t hear the music? You can come right out and tell me if you think I am crazy!” Ferdinand replies, “You are crazy” and hops on a boat to go to the island to kill the double-crossing Marianne and Fred. There are many comedic moments in Pierrot - at a gas station where the fugitive couple steal Ford Galaxie convertible (Godard’s own) off the pneumatic machine, the couple’s reenactment of Vietnam War at a pier for money where Ferdinand and Marianne play grotesque caricature of an American GI and a literal yellowface Vietcong are some of the prime examples. But five minutes of uncut reverie of Devos’s lovelorn loser routine is such an anomaly and comes out of left field at a pivotal, somber moment. Yet it comfortably fits into Godard’s antics- narrative dissonance that he cultivated both visually and aurally through the edits over the years.

About two-third way into Pierrot, the second detour to hands appears with Raymond Devos, a well-known comedian of that time period, who plays a nostalgic man striking up a conversation with Ferdinand/Pierrot at the dock, a place where betrayed Ferdinand/Pierrot embarks for his revenge. The man proceeds to tell a long and convoluted story, with wild gesticulations, about his lost loves. He says he hears music in his head all the time and keeps asking Ferdinand if he hears it too. “Est-que vous m’aimez…?” He keeps singing the song and we hear the music that is in his head, identifying with the man. He says he was wooing a woman by holding and stroking her hand. The story goes that he asked if she loved him, and she said no. The second woman said yes but he didn’t. The third woman said yes, and he held on to her hand for ten years. “You don’t hear the music? You can come right out and tell me if you think I am crazy!” Ferdinand replies, “You are crazy” and hops on a boat to go to the island to kill the double-crossing Marianne and Fred. There are many comedic moments in Pierrot - at a gas station where the fugitive couple steal Ford Galaxie convertible (Godard’s own) off the pneumatic machine, the couple’s reenactment of Vietnam War at a pier for money where Ferdinand and Marianne play grotesque caricature of an American GI and a literal yellowface Vietcong are some of the prime examples. But five minutes of uncut reverie of Devos’s lovelorn loser routine is such an anomaly and comes out of left field at a pivotal, somber moment. Yet it comfortably fits into Godard’s antics- narrative dissonance that he cultivated both visually and aurally through the edits over the years. The Devos scene reveals a lot about the fraught relationship between Godard and Karina. “With the end of his marriage to Anna Karina came the end of his quest for a form in which to represent and reinforce it; his new formless way of filmmaking mirrored a frantic state of mind that left no illusion of balance, finish, or grace.” (Brody 2009, 237) When Godard was visiting Serge Rezvani, a musician who contributed two songs that Marianne sings in the film, he was apparently struck by the harmonious relationship Rezvani had with his wife Danielle. “Gazing at the Rezvanis, Godard beheld, to his amazement, an artistic couple that was thriving. Godard’s subsequent contact with the couple, Resvani noted, showed how consumed he was by the problem - by his failure and their success.” (Brody 2009, 242) It makes sense, given Godard's personal, reflexive filmmaking, that he saw himself as the sad philosophizing clown who was betrayed. And underneath Devos’s funny antics hid the longing for the lost love and fantasy of that perfect union of artistic minds and unwavering support that he did not find in Karina. Therefore, through a glass darkly, Pierrot can be seen as a self-damaging, violent, dark fantasy reflecting on his real-life relationship.

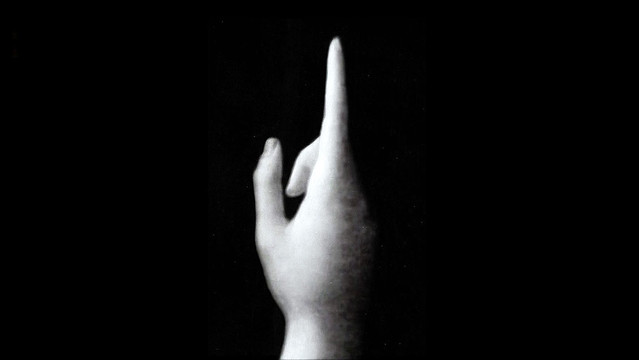

The visual and thematic motif of helping hand dominates Nouvelle Vague, Godard’s renewal of the new wave spirit in 1990. Not only the repeated close-up of hands that are shown in the film but thematically, from helping hands to a bum on the side of the road, pulling a drowning woman out of water, to lending a hand to the world in turmoil, the film is riddled with the metaphor of helping hands. Then there’s the pointing hand of Leonardo da Vinci’s St. John The Baptist in The Image Book, a hand over a naked young woman’s abdomen in Hail Mary, connecting the motifs with creation and divinity. In First Name: Carmen, an open hand covers the TV snow as if embracing the technology. In Film Socialisme, Patti Smith’s outstretched hands, trying to reach or caress the other side of the port, as the European Union tries to reconcile its colonial past. Thinking about all the visual motifs of hands in Godard’s filmography, I would say that this scene in Pierrot is perhaps the beginning where he incorporates the idea of helping hands.

The visual and thematic motif of helping hand dominates Nouvelle Vague, Godard’s renewal of the new wave spirit in 1990. Not only the repeated close-up of hands that are shown in the film but thematically, from helping hands to a bum on the side of the road, pulling a drowning woman out of water, to lending a hand to the world in turmoil, the film is riddled with the metaphor of helping hands. Then there’s the pointing hand of Leonardo da Vinci’s St. John The Baptist in The Image Book, a hand over a naked young woman’s abdomen in Hail Mary, connecting the motifs with creation and divinity. In First Name: Carmen, an open hand covers the TV snow as if embracing the technology. In Film Socialisme, Patti Smith’s outstretched hands, trying to reach or caress the other side of the port, as the European Union tries to reconcile its colonial past. Thinking about all the visual motifs of hands in Godard’s filmography, I would say that this scene in Pierrot is perhaps the beginning where he incorporates the idea of helping hands.

Pierrot le Fou reflects on a lot of social and political upheavals, as well as cultural trends of its time: The extreme right-wing violence, The Vietnam War, widely popular crime novels, rampant consumerism, yearning for simpler life and disillusionment of love. Every film needs to be seen and examined with a proper context. As reference heavy as Godard's films usually are, the visual motif of hands in Pierrot gives a great deal of insights to not only the filmmaker’s creativity and control over his craft, but outside the frame and his life in general. It all makes sense with Ferdinand constantly writing, in Godard’s own cursive and own words. Marianne, whom he thought he was in love with, turns out to be a double-crossing, morally lacking, consumerist manipulator. She’s not the like-minded sister-in-arms toward the artistic struggle. He tells her to “Shut up, I’m writing!” Twenty-five years old when they were filming Pierrot, Karina wanted to be free. Pierrot was the last collaboration between them and in his depressive state, he was able to exercise his dark fantasies one last time.

Pierrot le Fou reflects on a lot of social and political upheavals, as well as cultural trends of its time: The extreme right-wing violence, The Vietnam War, widely popular crime novels, rampant consumerism, yearning for simpler life and disillusionment of love. Every film needs to be seen and examined with a proper context. As reference heavy as Godard's films usually are, the visual motif of hands in Pierrot gives a great deal of insights to not only the filmmaker’s creativity and control over his craft, but outside the frame and his life in general. It all makes sense with Ferdinand constantly writing, in Godard’s own cursive and own words. Marianne, whom he thought he was in love with, turns out to be a double-crossing, morally lacking, consumerist manipulator. She’s not the like-minded sister-in-arms toward the artistic struggle. He tells her to “Shut up, I’m writing!” Twenty-five years old when they were filming Pierrot, Karina wanted to be free. Pierrot was the last collaboration between them and in his depressive state, he was able to exercise his dark fantasies one last time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brody, Richard. “Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard.” Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt & Co., New York, 2009

Kim, Jihoon. “Video, the Cinematic, and the Post-Cinematic: On Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinema.” Journal of Film and Video 70.2, Summer 2018

Martin, Sean. “New Waves in Cinema.” Oldcastle Books, 2013

Vishnevetsky, Ignatiy. “The Hand of Jean-Luc Godard.” Mubi Notebook Feature, December 25, 2018 https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/the-hands-of-jean-luc-godard

Une femme est une femme (1961) - Godard

Playful and vibrant, Godard's take on musical after massive success of Breathless is a pure joy. It vastly relies on the charm of Anna Karina who ignites the cinemascope technicolor screen. Paris is never more beautiful as Karina, Belmondo and Brialy roam around Raoul Cotard lensed, busy city, mostly unaware of their filmmaking shenanigans. It's good to see Godard celebrating youth and youthful optimism about the cinema before his cynicism and grumpiness took over. It liberating it must've felt. So many great moments. So exuberant! So lovely.

Détective (1985) - Godard

This all-star cast hard hitting noir riff is perhaps Godard's most playful film from the 80s. It concerns monsieur Jim (Johnny Holliday), a two-bit boxing promoter who owes money around town and a lonely wife, Françoise/Geneviéve (Natalie Baye) of a sad faced pilot (Claude Brasseur) of whom Jim owes money to. They are closely monitored 'with the shitty little Japanese video camera' by a gang of amateur inspectors - uncle Prospero, Neveu (Jean-Pierre Leaud) with the help of a perky little thing/would be Neveu's fiancée after she takes the school exam, Arielle (Aurelle Doazan). Jim has his posse of his own - Tiger Jones, a young boxer whose worst enemy is himself, princess of Barbados (Emmanuelle Seigner) and a young botticelli beauty (Julie Delpy) and an accountant who literally asks computer for solutions to every problem.

Jim not only owes money to the couple but also to a mafioso boss called Prince (Alain Cuny) who happens to be staying at the same opulent Paris hotel where everybody seems to be staying in. Actually, the whole film takes place in and around the hotel. The plot is way too discombobulating to follow along. There are some slight comments on technology and porn, but it's all about characters interactions, funny lines ('Damn Italian legs!'), mad slapstick energy (thanks to Leaud) and beauty of youth. Détective is an unabashedly silly, fun film reminiscent of Breathless.

Oh, Woe is Me/Hellas Pour Moi (1993) - Godard

I can't decide which Godard films have more beautiful images, as I go through his catalog. Oh, Woe is Me is certainly stunning, but proves to be one of the most inscrutable. Godard seems to suggest that there are limits to the image/film portraying the truth (and faith in god). As one character says, "I'm still touched by words." The film is in book chapters, its characters constantly talking about the existence of god in the modern world and representation of the truth. He ties the idea of faithlessness in the modern world with the limits of the imagery (now I think I understand better about nature images in his films). Then there is light/darkness dichotomy. In a stunning sequence, he closes the lens iris on a portrait shot of a beautiful model from overly exposed to complete black gradually, against undulating lake backdrop. The body gets easily overshadowed by darkness, but our spirit? "The night is for everyone, therefore more democratic," one character says in the beginning of the film. For everyone because they can hide their sins in darkness. God switches bodies with Simon (Gerard Depardieu) to be with Simon's beautiful, redhead school teacher wife, Rachel (Laurence Masliah). Is he pretending to be god or is it all her dream? Contemplative, invigorating, enthralling...just what the doctor ordered. This needs a definite rewatch or two.

For Ever Mozart (1997) - Godard

An old director Vicky (Vicky Messica) is about to direct a film called Fatal Bolero, about a war and suffering. It is largely financed by a seedy old gambling mogul who makes his girlfriend transcribe anal porn, word by word for his pleasure. Vicky holds a large audition for roles and rejects every one of them before they even finish one word from the line they were given. He doesn't want acting, he wants reality. In the mean time, his idealistic daughter Camile (Madeleine Assas), a philosophy professor, decides to go to war torn Sarajevo and put up some romantic play. Her lovelorn cousin Jérome (Frédéric Pierrot) and her Arab maid Rose (Ghalia Lacroix) follow her to her journey. Before they even get to Sarajevo, they are captured by Serb forces and anally raped and forced to dig their own grave and die during heavy bombardment. Rose escapes with one of the fighters who takes a shine to.

After getting the exhausted "Oui" from the actress (Bérangère Allaux of whom Godard was infatuated at the time) the non-acting acting he wanted, Vicky finishes Fatal Bolero with a huge boxy ancient film camera. The words get around that the film is shot on black and white and it's about war and suffering, the movie goers who lined up outside the theater peters out saying, "Let's go see Terminator 4 instead!"

It ends with a Mozart concert by a young orchestra. The audience take their seat, softly debating the weightiness of Wagner and light-heartedness of Mozart, having too many notes, etc. They are all waiting for a pianist to arrive. And he happens to be an effete young man with a long hair, playing beautifully. One of Vicky's overwhelmed (by the pianist's beauty) crewmember unwittingly becomes a page turner for the pianist. Exhausted Vicky listens to the concert at the top of the stair case he just reached.

Godard's condemns the passivity of France and Europe in general about another genocide taking place in their backyard, Bosnia-Herzegovina. He also plays with the theme of differences experiencing existence through body and spirit, representation of real events with a movie camera being nothing but a shadow, a generation (grand children of WWII generation) not purified but corrupted by suffering and guilt of their fathers weighing on them (Camile, a granddaughter of Camus). For Ever Mozart is not a heartless all out satire of Weekend. Camile & Co.'s action doesn't play out like a farce and characters drawn sympathetically. But Godard admits the limit to the power of art- that in the face of horror, even art is not enough to save the day. There is overwhelming sense of sadness and defeatism throughout the film.

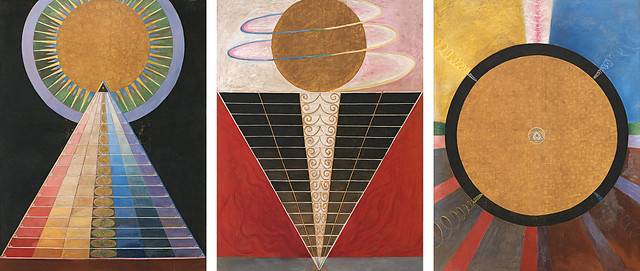

Passion (1982) - Godard

Film financing is a bitch. After reading Richard Brody's book on Godard, funding seems especially messy and difficult every time Godard have made his films. And many of his films are about, in some ways or another, making films. Passion is also one. Jerzy the Polish film director (played by Polish actor in exile, Jerzy Radziwilowicz) is trying to make a film in the West. Taking cues from the masters of western art- Rembrandt, Goya, Delacroix in a TV studio setting, he is trying to conjure up the opening scene. The production is stalled because of some unknown lighting problems and already 4 million over budget. With civil unrest in Poland in mind and under pressure by the film's Italian financiers while keeping his German wife Hanna (luminous Hanna Schygulla) happy and entertaining the possibility of getting involved with a beguiling, Wałęsa inspired factory worker Isabelle (Isabelle Huppert), Jerzy's struggling to keep everything under control. There are talks of censorship, public appeasement and subversiveness in art, in relations to those masters work and film. Is going to the USA, just like his producer and only friend (László Szabó)'s suggestion, the end of all problems or end of creative freedom?

As usual, Godard mixes up current political affairs with his lifelong examination of film medium, the rise of video technology, beauty, representation of truth in art. The usual slapstick comedy is there along with discordant soundtrack and out of sync dialog. The other Godard regulars include Michel Piccoli as the ruthless and greedy factory boss, Miriem Roussel as deaf-mute ingenue. Again, Raoul Coutard provides some beautiful images and there are so many babes/boobs in this movie. Another delicious concoction.

Prénom Carmen/First Name: Carmen (1983) - Godard

Godard himself stars as uncle Jean, a burnt out movie director in a mental asylum and the uncle of a beautiful girl named Carmen (Maruschka Detmers), just like the femme fatale in Bizet's opera. Here Godard equates filmmaking to armed robbery and playing a piece of music. During a bank job, Carmen falls in love with the security guard Joseph (Jacques Bonnaffé) and they run away to the coast and lay low before the gang reunites. There is parallel storyline simultaneously happening- a quartet is rehearsing a Beethoven. They constantly stop and readjust because they make mistakes, are not playing violent enough, too slow, inaudible, etc,. It's the usual Godard stuff- fragmented, playful narrative with the mesh up soundtrack of tides, trains, Beethoven and Tom Waits.

It's Godard's reflection on filmmaking in the 80s where video ruled -there are constant references to videotapes and video cameras. It's not quite successful as his later attempts looking at art, film, the world. Here he tries many different things. It has a lot of physical slapstick comedy in it. Too bad I'm not really a big fan of that. But Godard is funny here in a similar way Woody Allen is in his films. All in all, Carmen plays out like a rehearsal for better things to come.

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991) - Godard

The film is Godard's contemplation of Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The aged Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine) from Alphaville, slated as the last spy, marooned in East Germany, wanders across grey landscapes asking in French, "Which way is the west?" to equally confused bystanders. There are no similarities between the two films. Godard merely re-appropriates Caution as the archetype of cold war (in itself a parody) whose stone carved face stood on a solid ground and even more solid philosophy. Some thirty years later, he is nothing more than a relic and out of his element.

Godard is as critical of the failure of communism in the East as the Germany's Fascist past and rampant capitalism of the West. With jarring grey old film clips playing constantly sped up or slowed down and the classical music soundtrack by the greats- Liszt, Mozart, Bach, 90 Nine Zero is also contemplates the decline of culture and art. It works better in the last third when Caution finally reaches the West. He notices an East German girl he saw before, working as a maid in a fancy hotel he is staying in. He asks, "So you wanted to be free, huh?" and she answers, "Work makes you free (Arbeit macht frei)," which was the trademark of the concentration camp slogan. It is fitting even in the opulent west. With the soundtrack by Mozart, Liszt and Bach, 90 Nine Zero is yet another beautiful, biting one by Godard.

Sauve Qui Peut/Every Man for Himself (1980) - Godard

While his usual themes- capitalism/prostitution/filmmaking are still present, this film is a giant leap forward from his sixties stuff which are filled with grand, in your face metaphors and loud political ideology that I constantly find prolonged and boring (but I still have soft spot for Week End). Every Man for Himself, with its 87 minute running time is more concise and extremely watchable (whether it was Godard's intention or not). It concerns a tv producer Paul Godard (Jacques Dutronc) and a prostitute, Isabelle (Isabelle Hupert). Paul is juggling with his ex-wife and daughter, girlfriend (Natalie Baye) and work. He is a pretty typical modern male in Godardian universe - an asshole who can't express love and when he does, it only comes out violently (to be fair, he gets his hair pulled, slapped in public and meets a grisly death).

Godard's sardonic tendencies are still very much pronounced, especially in a frank and graphic voice-over conversation between two fathers about their daughters over the image of a pre-adolescent girl (Paul's daughter). Isabelle and her younger sister's 'getting into business' talk is also effectively disgusting. Then there is 'aye-ah-hey' human Rube Goldberg sex contraption- the visualization of capitalism and commerce, which is hilarious and sickening at the same time (sicker than Human Centipede).

Godard's use of the slow motion is intentionally abrupt and disjointed. Rather than using it to smooth the action or show time passing, he accentuates the violence. Soundtrack is used in the same way, whenever characters are trying to draw conclusions or about to say something meaningful to each other, they are interrupted by phone calls, sudden music, train, etc. Endlessly amusing and very watchable, Every Man for Himself is a good introduction for me to get in to more 80s Godard.

Film Socialisme (2010) - Godard

Intentional or not, Film Socialisme coming out just before the Arab Spring and the collapse of the Greek economy (the ship sails from Egypt to Greece along various ports) is a hearty validation of Godard's acute observations of Europe and its colonial past over his long career. Here Godard sees a giant cruise ship as a metaphor for Europe- decadent, crass, greedy people enjoying luxury largely serviced by non-European workers, sailing an uncharted territory surrounded by ominous, choppy water. But like always, everything is double edged sword in JLG world. Like the British leaving Palestine and Quo Vadis. But the film is much more than that. Incorporating 35mm, grainy videophone, HD stills and youtube videos, he envisions the filmmaking as a democratic medium, hence the title. Does it always work? No. But it's still darn interesting.

Typical Godard techniques are present. But he puts even more emphasis on visual storytelling by putting fractured Navaho English subtitle. One might see this as just another Godard snub against English speaking viewers, but when one watches a Godard film, most of the dialog goes over his head anyway. I thought this was brilliant and a vast improvement from the irritating presence of actual American Indians in Notre Musique. The next text after above screenshot is ...killing Blacks. When watching a JLG film, one can't take his loaded images and texts at face value, for that is not his actual opinions. They are archetypes in a movie, like Gary Cooper in High Noon.

Strangely, a token American featured is singer/poet Patti Smith. Why would she be on a cruise ship? He's just a big fan?

My classical music knowledge is very limited and I don't really know when people talk about symphony in three movements and Film Socialisme. Yes the film is in three parts (but not your typical, concise three act structure). After the first act at sea on a cruise ship, we are introduced to a family in a remote gas station. TV reporters armed with a small video camera hounds every movement of the family. This thinly disguised as Reality TV parody segment features some of the most visually stimulating and perhaps most hopeful scenes.

Always at the dead center of the frame, youth- always epitomized by beautiful teenage girls in his films, are curious, smart, funny and willing companions in discussions who are not 'corrupted by suffering and humiliated by liberty' while acknowledging the past.

The third part of the film starts with montages of war atrocities. There are still much I don't really get- his notion of Nazi gold and Soviets and Odessa Steps are lost on me. Film Socialisme starts out strongly but kind of fizzles at the end. But as always, watching JLG films is always an invigorating experience.

Adieu au Langage (2014) - Godard

3D seems like it is here to stay, for now. It was a gimmick to win back the audiences the film industry lost to the emergence of TV in the 50s', now it is revived as a last ditch effort to save the ailing industry, probably until TV starts broadcasting its contents in 3D (as we all know, it's only a matter of time that we'd be enjoying our football games and movies at home with silly glasses on). But can this new/old technology be elevated onto an art form, rather than being used exclusively to show us a mangled hunk of metal/asteroid as it hurtles toward us? If Herzog's awe inspiring Cave of Forgotten Dreams and now Godard's Goodbye to Language were any indications, the answer is yes. Yes it can.

Always on the forefront of visual experiment and testing the limits of cinema, 3D seems to be a logical next step for Jean-Luc Godard to sink his teeth in. After his test run with the technology in a short Three disasters (his contribution to an omnibus project, 3X3D), JLG, at 83, is fully committing to the 3D technology with Goodbye to Language.

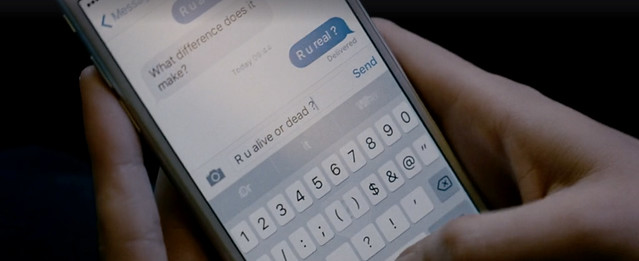

The film starts with a quote, "Those lacking imagination take refuge in reality." With that, there is a slight narrative, concerning a couple (or two) as they bicker and contemplate murder. Women in the film are very much alike (a typical Godard heroine archetype- brunette with dark eyes) and tend to shed their clothes often. An outdoor book market becomes the flash point for the old and new. While browsing for books by Dostoevsky, Solzhenitsyn, people furiously text and exchange their mobile devices. The bookseller shouts from his chair, "Don't bother googling Solzhenitsyn!"

"One day everyone will need an interpreter for what he says." One of the characters utters in the film. Its biblical implication of the world in chaos aside, the film is packed to the brim with visuals. Divided in 2 parts or at least in that Godard's typical chapter headings - Nature and Metaphor, the film grimly/comically announces the death of language.

The most vivid character is perhaps a dog named Roxy (Godard's beloved mutt), who graces the screen with his adorable face in about half of the 70 minute feature, playing around in nature, in all four seasons - near lake Geneva I'm assuming, generally having a good time. Godard's contemplation of war is there, but this time, not as specific or pointy as in his earlier films. Still, playing cinema's enfant terrible, he includes shots of burning bodies, and even graphic sex images. The sporadic, jumbled subtitles and dialog appear and repeat, accompanied by equally disjointed soundtrack - Beethoven and Tchaikovsky.

Layering clear HD, pixelated DV, and other grainy archival footage as thick as Dostoevsky novel, Goodbye is denser, more uncompromising, more impenetrable and less coherent than Godard's last outing, Film Socialisme (which I adored). But it's still a marvelous trip. OK. let's talk about the 3D aspect of the film. There is the usual JLG droll word games with his trademark bold titles-- Adieu (in Adieu au Langage) becomes AH, DIEU (Oh, God). Only this time, it's in 3D! People's everyday actions and nature scenes, like drinking from outdoor water faucet or a sunset or sunflower field on a windy day, become cinematic events.

Imagine some of the most visually sumptuous JLG films from his later period. Nouvelle Vague (1990) or Hellas Pour Moi (1993) for example - the ship sailing by in the background, the foggy field, swinging light bulb overhead, a long dolly shot looking through the window. Now picture them in 3D. This is what Goodbye to Langauge is like. It's a thrilling visual experience and I thank god for JLG embracing the gimmicky technology and using it in his tireless exploration of the boundaries of cinema. Ah-Dieu indeed. It's certainly one of the year's best.

Goodbye to Language made its debut at this year's Cannes Film Fest, then TIFF. It is playing at NYFF on 9/27 and 10/1. Please visit FSLC's website for more info.

JLG JLG: autoportrait de décembre (1994) - Godard

This is my initial thoughts on JLG JLG (will have to rewatch very soon):

With Anna Wiazemsky passing this year, it hit me that Godard, who just turned 87 today, outlived most of his contemporaries. Even though lately he hasn't been as prolific as past several decades, he is still at it. With JLG JLG, which came out more than 20 years ago now, in his 60s, I think his carrier gave him a chance to look back to see what he had gained, what he had lost. He looks mighty lonely at the empty shore of Lake Geneva.

Godard tells that JLG JLG is not a autobiography, but autoportrait near the end of the film. The year is 1993- The Bosnian War is still raging, Israel/Palestine conflict saw the signing of the uneasy Oslo Accord after much bloodshed and injustices, European Union was formed to compete economically with America. The film reflects Godard's contemplation on these matters and mortality, art and culture, and of course, cinema.

Dark empty corridors contrasts wintry landscape of Lake Geneva, as Godard narrates in his usual intentionally distorted, gravelly voice. The scenes are accompanied by hollow footsteps and nature. But usually the shots are mostly devoid of humans. He appears on screen, scribbling and reading, conversing with nubile housekeepers. There are a peach fuzzed studio exec who looks like 19, a blind assistant editor and an old woman who's sitting in the snow ominously speaking in Latin.

Godard's seemingly abstract connections through politics, history and art are not without fangs. Like light and darkness, there's two sides always competing, but what if there is only one side but the other is just an reflection of one's self? "JLG by JLG," he says at one point. It's only you who can truly represent yourself and on the same token, truly judge yourself. "I am legend." He declares on the pages of his note book- he is thoroughly aware of his past. The past is never dead. He's the director of Breathless and Pierrot le fou among others. But over the years, his persona (his name) has taken over a center stage rather than his films. How do you reconcile the two? He also has to live up to his name. With everything that was going wrong in the world at the time, speaks of love, as if there is a chance in the rotten world that gives us meaning to all of this. He will be remembered in art history. He is legend. He has been tirelessly exploring and in turn, elevated cinema as an art form. Happy Birthday Monsieur Jean-Luc.

Livre d'image/Image Book (2018) - Godard

With Image Book, Jean-Luc Godard is still at it at age 87. With his presence strongly felt at Cannes this year with its poster of Belmondo and Karina kissing from Pierrot le fou (purely out of their nostalgia trip and other superficial reasons) and Cate Blanchet led Jury ironically awarding him 'the Special Palm d'or', whatever that means. But in stark contrast to youthful exuberance and liberty of his earlier films, Image Book is in large part and as expected, dark, brooding and more inscrutable than ever and indirect condemnation of the cheap spectacle the festival has become. Completely consists of existing footage - from Hollywood, European and Soviet films, war atrocities, news footage of ISIS and films from the Middle East in later part, Godard grimly goes on about the power, or lack thereof, of images in his raspy, groveling voice over.

Like most of his essay films since the monumental Histoire du cinema, his fragmented, loosely connected images have been, if not anything, reminder of the terrible history of humankind. Image Book is no exception. With Bertolt Brecht's quote, "Only a fragment carries a mark of authenticity," he somewhat frees us from dwelling over his use of edits - how he cuts two images together, how he stops and drags an image, his discontinuous soundtrack, spastic English subtitles and digital manipulation where colors bleed and image become almost abstract. Truth is in the images themselves. And as far as collages go, it's an assault on your eyeballs, very much like that famous shot from Un Chien Andalou which he references to in the film.

His thin image thread is there with the picture of hand pointing up, renaissance paintings where gestures have hidden meanings to recognizable movie clips include Vertigo, Kiss Me Deadly, Ivan the Terrible, Dr. Mabuse, Johnny Guitar, many from his own filmography and countless others I don't recognize. Train shots from various films invariably ends up in Auswitz footage. With Godard saying, "I have the courage to imagine. I take the train of history and I think of people who take the train for a job and who do not have courage to imagine." With images of 35mm film going through a projector, its thick and hammy celluloid strip jittering through the loop like a convulsing snake or slap of meat going through a tenderizer, Godard puts emphasis on the physicality of communication, the visual language, rather than spoken one.

The second half of the film settles into West's notion of Middle East as it was chastised by Edward Said in Orientalism. With barrage of film clips from old Egyptian films and other Middle Eastern nations, Godard examines An Ambition in the Desert, a book by Albert Cossery, an Egyptian born French writer. The book tells a story of a imagined Middle Eastern emirate of Dofa, a non-oil producing state therefore escaped from the Western colonialists' influence. It's deemed as paradise in the Middle East. Series of explosions rocks Dofa and Samantar, the main character of the story, would find out the attacks are planned by machiavellian Prime Minister of the emirate, Sheik Ben Kadem, who welcomes the influence from the west for his own political gain. Godard delves deeply into the subject, juxtaposing old Egyptian movie clips, surveillance ISIS footage and everyday street footage digitally manipulated to abstraction.

Godard's latest offerings are hard nut to crack, even more so than usual. Image Book is also the ones that needs to be mulled over after viewing. I didn't know about Cossery's book. I had to look it up. Even as an avid fan of his filmography, most of the stuff he talks about go over my head. But with Image Book, there seems to be a concerted effort for Godard to point us in the direction where he sees a corner of the world that is underexposed, underseen and misrepresented by the western world. He references his 1987 film King Lear a lot in Image Book, especially a shot of Cordelia (Molly Ringwald)'s dead body lying on the rock - as if telling us that Cordelia, the righteous, virtuos one, is dead and there is no good one left in the world. He also leaves in his coughing fit during the middle of voice over. Godard knows his time is almost up. There is a sense of urgency in his gravelly voice. Say what you will about cranky attitude, his stubbornness all these years not to conform, his perceived snobbiness. Yes, the representation and how you tell the story matters. But I'd rather get dictation from Godard and have him point me to the right direction than from anybody else. I sincerely hope Image Book is not his farewell message to the world.

Les Trois Désastres (2013) - Godard

Before Goodbye to Language (2014), where Godard embraced 3D as another art form, he participated in 3X3D, omnibus project commissioned by EU. I won’t even mention the other two shorts by other directors because they were terrible. But The Three Disasters, is a continuation of Godard’s contemplation on art and cinema. His wordplays are strong here: des =dice, astres=stars… as if predicting Hollywood’s short romance with the medium (again) as a gamble. “Writing was necessary. Printing was gratification. Digital will be dictatorship.” He drawls in his gravelly voice. He also observes the invention of perspectives in Western art ruined having any depth in content, correlating it to 2D and 3D in cinema. It’s Invigorating 20 minutes as any of his other films.

Before Goodbye to Language (2014), where Godard embraced 3D as another art form, he participated in 3X3D, omnibus project commissioned by EU. I won’t even mention the other two shorts by other directors because they were terrible. But The Three Disasters, is a continuation of Godard’s contemplation on art and cinema. His wordplays are strong here: des =dice, astres=stars… as if predicting Hollywood’s short romance with the medium (again) as a gamble. “Writing was necessary. Printing was gratification. Digital will be dictatorship.” He drawls in his gravelly voice. He also observes the invention of perspectives in Western art ruined having any depth in content, correlating it to 2D and 3D in cinema. It’s Invigorating 20 minutes as any of his other films.

Two or Three Things I Know about Her (1967) - Godard

Not as angry as Weekend, but as cynical as Godard can be, Two or Three Things attacks American style consumerism relentlessly in Paris projects background. In Godard's eyes, Paris of 1966 is one whole construction site not dissimilar to Antonioni's world.

In order to afford all the comfort of modern living, or name brand dress, a low-class housewife and mother of two, Juliette Jesen (Marina Vlady) resorts to prostitution. Raoul Cotard's cinematography (in anamorphic format and technicolor) here is all pop.

It seems Godard is not really interested in actors despite Vlady's lovely hot mama. It probably had to do with Godard's breakup with Anna Karina and Vlady's rejection of his marriage proposal still fresh right before shooting of this film. But objects in this film, as he narrates in hushed whispers about objects and subjects and objects and people, has more importance. At one points he whispers that 'objects are more alive and people are already dead'. With that, a cup of black coffee becomes our galaxy.

Godard's idea of language vs images is strong in this film. He plays with iconic posters, brand names and signs to illustrate the easily malleable nature of words.

With Vietnam War still raging, Godard has a lot to say about American Imperialism and rampant capitalism it represents. 'America über alles' as one of the characters says.

19-year old Juliette Berto is a stand in for Anna Karina in an extended cafe dialog scene as she flirts with the intellectual garage worker husband of Jesen (Vlady).

Trapped in crude capitalist system, everyone has to prostitute himself to live. Vlady's Juliette remains distant as she addresses directly to the camera, emotionlessly. She is not a hapless victim but a willing collaborator in the monstrous system and therefore deserves Godard's contempt.

Alphaville (1965) - Godard

Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine), a hard-boiled spy from outland arrives in the Orwellian city of Alphaville, where people are controlled by a super computer named Alpha 60. The all the girls have numbers tattooed on their body and have no emotions. Words are disappearing every day and people get executed if they behave 'illogically'. Caution meets his predecessor Henry (Akim Tamiroff) who dies mysteriously after feeding him a bit of information on Prof. Von Braun (Howard Vernon) who invented the Death X-ray. Then he meets enchanting Natasha Von Braun (Anna Karina) who gets intrigued by the unpredictable outlander.

The setting is minimal. The 60s Paris doubles as the modern megalopolis. Godard's mash-up of noir and B-grade sci-fi films has its moments, especially the pool execution scene with the knife wielding synchronized swimmers. For a Godard film, it's surprisingly accessible, thanks in parts to constant narration by the gravelly voiced supercomputer. Yet it's a complex film. It's a satire on the advanced, soulless capitalist society and mainstream movies. It also examines the question 'what makes us human?' Caution is not your regular straight-up 'good' man. He says gold and women when asked about his desire at the interrogation. But he also reads surrealist poetry, so.... I didn't care for the 'love conquers all' ending (has a lot of similarities with Blade Runner) but it's an interesting little film nonetheless.

Keep Your Right Up/Soigne ta droite (1987) - Godard

Godard presents himself as Prince Mishkin in Keep Your Right Up. He is a director who needs to deliver a finished film in a breakneck pace to some philosopher quoting industrialist who will pay top dollars for it. The director is seen as a bumbling idiot who doesn't know which way is up or down or east or west. But as always, he deals with grander themes - mortality, nature vs technology and of course, cinema.

The film has three distinctive narratives running concurrently, cutting back and forth. One is with the Buster Keaton-ish idiot's journey on the road, the other one is about musicians, the 80s French pop band Les Rita Mitsouko (Fred Chichin and Catherine Ringer) as they compose and rehearse their musical numbers and lastly people going somewhere by car, plane and train, immobile and mobile at the same time.

Music is great. Les Rita Mitsouko's synth, rhythm box heavy pop is very catchy and Ringer's deep, sexy voice is infectious. Godard manipulates the sound like he does with images, using Mitsouko's recording sessions- playing with layers of studio recording. It's the creative process he is equating with music, as he had done since the beginning of his career, albeit crudely arranging two tracks of optical audio (as you remember dialog cutting off abruptly and replaced by music and vice versa). The later more sophisticated examples are Forever Mozart, Nouvelle Vague. This film would be a more polished/improved version of that experimentation. Bright primary colors are there, so as madcap slapstick, clusterfuck comedies of yesteryears. Keep Your Right Up feels freer and even more energetic than Godard's other films in the 80s- playing a fool and not taking himself seriously probably helped. It might be minor Godard, but no less fun.

King Lear (1987) - Godard

"Instead of King Lear having three daughters, Cordelia has three fathers - a writer, writer playing the role of the writer and myself, the director" quips Godard in a gravelly voice. The writer in this case is Norman Mailer. He says he can only do King Lear as a gangster film. Thus Lear becomes Don Learo. Learo is sniveling Burgess Meredith and Cordelia is Molly Ringwald. The setting is Nyon, a lakeside Swiss town. Chernobyl happened and wiped out the whole civilization. Movies and art are lost. The 'image' needs to be reinvented. A Shakespeare's descendent (theater director Peter Sellars), is trying to rediscover all the great plays of his ancestor and he finds an inspiration from the old man (Meredith) and his young daughter (Ringwald). In the meantime Prof. Pluggy (videowire dreadlocked Godard, gruffing in English from the side of his mouth and sounds like as if Meredith had a stroke, plays basically a cultural shaman) with his young minions, Edgar (Leos Carax) and Virginia (Julie Delpy), is trying to create the image with the help of sound (multiple voiceovers, waves, seagulls overlapping and interrupting dialog). Sound is important because it relates to the silence of Cordelia. There is a parallel rediscovering 'movie' and 'art'.

Godard juxtaposes old men's penchant for young beautiful girls, from Renoir the painter to Renoir the director with King Lear, the powerful, dying, demented and Cordelia, the young, virtuous but untender and a bloody bedsheet, suggesting incest (hence the appearance of Woody Allen at the end or pure coincidence?). The words are cheap and Cordelia doesn't wear her heart on her tongue. He also comments on the doomsday scenarios (Chernobyl just a year before) and dominant video technology vs film - there is a scene where a reel of film discarded in the forest being rescued by Carax. It's less cinematic and messier than his other 80s films and a little jarring to hear everyone speaking English in this Godard's first and only English feature, but his playfulness is there and the choice of 80s teenqueen Ringwald as Cordelia makes a lot of sense here.

Une femme mariée (1964) - Godard

Macha Méril's Charlotte is a coquettish married woman vacillating between two men: a brutish plane obsessed husband (Philippe Leroy) and a narcissistic actor lover (Bernard Noël). It starts out with the static shot of each body part of Charlotte. Her days are spent on shopping, going to the cafes and the movies. She finds out that she is pregnant but doesn't know who the father is.

Macha Méril's Charlotte is a coquettish married woman vacillating between two men: a brutish plane obsessed husband (Philippe Leroy) and a narcissistic actor lover (Bernard Noël). It starts out with the static shot of each body part of Charlotte. Her days are spent on shopping, going to the cafes and the movies. She finds out that she is pregnant but doesn't know who the father is.

Godard's take on women being objectified in the consumerist 60s is on full display here. Also the talk of holocaust hangs like a cloud. Charlotte doesn't know what Auschwitz is as the men talk about it on the way back from the nazi trials in Hamburg. Biting and provocative.

Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars (2023) - Godard

It's hard to believe that it's been a year since Jean-Luc Godard left us forever in his own volition. His last moving picture, a twenty-minute preview of his contemplation on the state of the world we live right now, Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars, is a testament to his legacy as the most unique film director ever lived in cinema history. Originally wanting to adapt a communist Belgian writer, Charles Plisnier's Faux Passport in 2020, Godard began to create a book of collages based on the book's six chapters. But the project stalled because of Covid pandemic. So, he decided to make a trailer for the project, a snapshot of a film to come, according to Godard's close collaborator Fabrice Argano.

It's hard to believe that it's been a year since Jean-Luc Godard left us forever in his own volition. His last moving picture, a twenty-minute preview of his contemplation on the state of the world we live right now, Trailer of the Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars, is a testament to his legacy as the most unique film director ever lived in cinema history. Originally wanting to adapt a communist Belgian writer, Charles Plisnier's Faux Passport in 2020, Godard began to create a book of collages based on the book's six chapters. But the project stalled because of Covid pandemic. So, he decided to make a trailer for the project, a snapshot of a film to come, according to Godard's close collaborator Fabrice Argano.

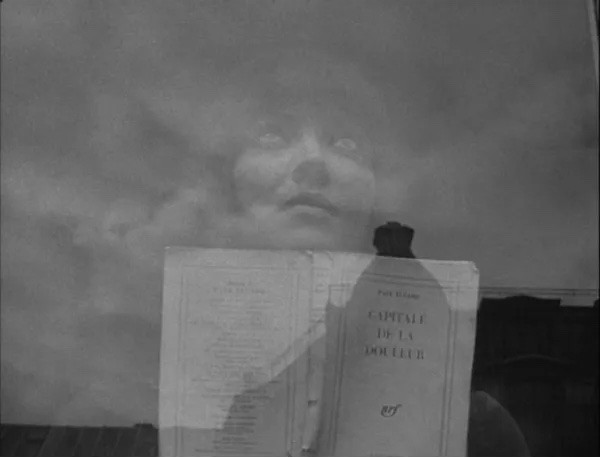

It's a series of his hand made collages on A5 Canon glossy printing paper with sporadic sound. With no sound for first five minutes, I was yearning to hear his gravelly voice one last time and was relieved to hear it again when he narrates about Carlotta, a heroine of short story by Plisnier, which he wanted to adapt. He says that the writer made portraits and it intercuts with the Olga Brodsky's face in the scene from his 2004 masterpiece, Notre Musique. And it turns out that that's the only 'moving image' we see in this short preliminary image book for a film that will never be made. It's also a rare glance into Godard's process in constructing his films. It's hand-made images - with pens, markers and underlined words and instructions, with photos, paintings glued on. And with sound, film, video clips and music combined, building/constructing thoughts for his essay films. And it's fascinating.

Plisnier turned his back on communism and Stalinism and became a Roman Catholic in his later years. Through the sound clips from Notre Musique, you hear the character replying to a Russian soldier, "I don't understand what you are saying, I do not trust that language." And I can't help him connecting it to the current situation in Ukraine. Godard had always been a keen observer, an oracle, and an ardent critic of the aggressors of the world. He knew which side he was standing on. It would have been great to see what his take on the whole situation with more elaboration.

Because he always charted his own course from the very beginning, Godard had no disciples or imitators. Each of his films were borne out of his unique method and technique and there's no substitute for his filmmaking. As the twenty-minute Trailer ends, realizing that this is the final official release of his moving-picture (even though I know for a fact that there is wealth of materials he left behind), that this is indeed the end of it, filled me with great sadness. No more Godard. This is it.

Grandeur et décadence d'un petit commerce de cinéma/Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company (1986) - Godard

Godard was commissioned to make a TV film as a part of Série noire, a monthly film noir series, based on pulp fictions. His was supposed to be based on James Hadley Chase's Soft Centre. But it being adapted by Godard, obviously, wildly went off the rail. With the little success and financial stability from Hail Mary (thanks to Nicolas Seydoux, the head of French film studio Gaumont, who hired Godard on salary for his future film rights), Godard had established a small film company, dabbled in mini-industrial film production. But because of this little business venture, he had to deal with tax collectors scrutinizing every receipt and every financial record keeping for his highly unorthodox filmmaking activities. So instead of making an adaptation, Godard made Grandeur et décadence into, yet again, a deeply personal reflection on his filmmaking process and art. This video shot production is about a film producer Jean Almereyda (Jean Pierre Mocky, assuming Jean Vigo's real name), trying to keep his production company afloat, while dodging the German mob whom he owes huge amount of deutschmarks to, and a film director Gaspard Bazin, yes, Bazin (Jean Pierre-Léaud), embarking on a noir project based on Chase's novel with 'authentic' actors.

Godard was commissioned to make a TV film as a part of Série noire, a monthly film noir series, based on pulp fictions. His was supposed to be based on James Hadley Chase's Soft Centre. But it being adapted by Godard, obviously, wildly went off the rail. With the little success and financial stability from Hail Mary (thanks to Nicolas Seydoux, the head of French film studio Gaumont, who hired Godard on salary for his future film rights), Godard had established a small film company, dabbled in mini-industrial film production. But because of this little business venture, he had to deal with tax collectors scrutinizing every receipt and every financial record keeping for his highly unorthodox filmmaking activities. So instead of making an adaptation, Godard made Grandeur et décadence into, yet again, a deeply personal reflection on his filmmaking process and art. This video shot production is about a film producer Jean Almereyda (Jean Pierre Mocky, assuming Jean Vigo's real name), trying to keep his production company afloat, while dodging the German mob whom he owes huge amount of deutschmarks to, and a film director Gaspard Bazin, yes, Bazin (Jean Pierre-Léaud), embarking on a noir project based on Chase's novel with 'authentic' actors.

You can trace Godard's standard preoccupations - word play: "You know where the word secretary originates? 'Secret'," "Original...origin," and so forth. - experiments with video technology: rewinding and slowing down images, the glitches, etc. - beauty and authenticity of actors: revolving door of a screen test, an accidental actress, fame. - Cinema's place in the age of television and nostalgia: "Everything is going backwards today- fashion, politics, and whatnot. The cinema is going backwards too... So maybe since she (Eurydice, played by Marie Valera) is old-fashioned, she has a chance. To each his own freedom, after all. But you have to land in the right place. It's not a question of time or of era, it's a question of tempo." - classics: Western culture and Greek mythology.

In the end, Eurydice looks back and Jean meets his untimely end despite his disguise as a babushka to ward off the mobsters. Léaud, donning a dirty moustache, does his utmost best as an arrogant auteur whose casting antics - where auditioning each actor says the snippet of the words from Faulkner like an assembly line of word generators, get comeuppanced by auditioning for fashionable group of young people who took over Jean's office after his untimely death.

Again, as the title suggests, Godard bites the hand that feeds him. His plunge into Histoire(s) du Cinema only 4 years away, Grandeur et décadence shows him and his new cinematographer Caroline Champentier (who is in the film also as the wife of the director) experiment with video - slow zoom in, multi-layered dissolves, playing the defects of tape-based technology on images. It's a fun film.

Phantoms in the capitalist system in Vagabond, Germany Year 90 Nine Zero & Personal Shopper

A phantom, a specter, a ghost, a spirit, or what Heidegger termed as “ontological obscurity, (Derrida, p461)” is closely linked with cinema. Seeing flickering moving images projected on the screen, one must connect the question of technicity with that of faith. A phenomenon of belief, of “pretend as if,” is an inherent quality of the narrative film. The spectral dimension is neither the living nor the dead, neither hallucination nor perception. According to Jacques Derrida, “Cinema is the image grafted from the past, a spectral memory, a magnificent mourning. (Baeque, Thierry, and Kamuf, p27)”

It’s that mourning part of Derrida’s discussion that I want to examine and draw the correlations to the idea of phantoms in the capitalist society in which we live in, in three different films, Germany Year 90 Nine zero (Godard), Vagabond (Varda) and Personal Shopper (Assayas). Each director has a vastly different approach to cinema. But they have some common threads running through all their films; changes in society, advancement of technology and its effects and the exploration of cinema/personal history. But moreover, I believe there are sharp critiques of capitalism in these three films and similarities in their calls for the need of spirituality in our society.

A phantom, a specter, a ghost, a spirit, or what Heidegger termed as “ontological obscurity, (Derrida, p461)” is closely linked with cinema. Seeing flickering moving images projected on the screen, one must connect the question of technicity with that of faith. A phenomenon of belief, of “pretend as if,” is an inherent quality of the narrative film. The spectral dimension is neither the living nor the dead, neither hallucination nor perception. According to Jacques Derrida, “Cinema is the image grafted from the past, a spectral memory, a magnificent mourning. (Baeque, Thierry, and Kamuf, p27)”

It’s that mourning part of Derrida’s discussion that I want to examine and draw the correlations to the idea of phantoms in the capitalist society in which we live in, in three different films, Germany Year 90 Nine zero (Godard), Vagabond (Varda) and Personal Shopper (Assayas). Each director has a vastly different approach to cinema. But they have some common threads running through all their films; changes in society, advancement of technology and its effects and the exploration of cinema/personal history. But moreover, I believe there are sharp critiques of capitalism in these three films and similarities in their calls for the need of spirituality in our society.