Since the beginning of cinema, music has been an integral part of filmmaking: from silent era films accompanied by live music on stage, to Golden Age of musicals in 1930s- 50s, to orchestral arrangements of individual composers such as Elmer Bernstein, Ennio Morricone and Morris Jarre in the 60s, and jazz and pop composers such as Henry Mancini, Lalo Schifrin, Herbie Hancock. By the late 1960s, even though there were still many music themed films made in Hollywood, the costly musical genre had all but died out. With troubles abroad - the Vietnam War, and at home - anti-war protests, race riots and political assassinations, the new generations of Hollywood filmmakers decided to reflect the mood of the nation not only in their films but in music as well by working with seasoned and popular musicians who were in transition themselves.

Since the beginning of cinema, music has been an integral part of filmmaking: from silent era films accompanied by live music on stage, to Golden Age of musicals in 1930s- 50s, to orchestral arrangements of individual composers such as Elmer Bernstein, Ennio Morricone and Morris Jarre in the 60s, and jazz and pop composers such as Henry Mancini, Lalo Schifrin, Herbie Hancock. By the late 1960s, even though there were still many music themed films made in Hollywood, the costly musical genre had all but died out. With troubles abroad - the Vietnam War, and at home - anti-war protests, race riots and political assassinations, the new generations of Hollywood filmmakers decided to reflect the mood of the nation not only in their films but in music as well by working with seasoned and popular musicians who were in transition themselves.Also, Hollywood was taking notice in the Black audience market, which accounted for 30 percent of all movie-going public at the time. Driven by demographics, economics, and the political realities of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, the studios hired their first black directors, who would redefine the African American image on the big screen. And who would they choose to collaborate for their motion picture soundtrack? Naturally, the biggest and most popular names in music of the era. And these Black filmmakers understood the power and sway of music on general audiences.

One can’t ignore the Blaxploitation phenomenon when discussing African American filmmaking or black representation in the 1970s. The African American community had entered a new phase in the Black Freedom Movement. America was witnessing a political shift from African Americans engagement primarily in non-violent Civil Rights tactics towards their participation in move vociferous Black Power actions. (Acham P.113) Long simmering tensions boiled over across the United States in July 1967, with violent rebellions - labeled “race riots” by the press - exploding in New York, Detroit, Milwaukee, Toledo, Houston, Newark, and other cities. President Lyndon Johnson’s Kerner Commission found systematic racism that Governmental institutions failed to address the poverty, crime, drug addiction, joblessness, inequality, poor housing, and general hopelessness growing in many African American communities. (Ryfle p.12) Sidney Poitier became number one box office drawer in 1967. His success was based on mainstream US acceptance of the roles that he played which were typically sidekick characters who supported white counterparts in obtaining their dreams. Poitier was now seen as an integrationist hero and was considered behind the times. (Acham p.113)

After the success of films such as Sweet Sweet Baadasssss Song (1971), Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970) and Watermelon Man (1970), black themed movies were generally marketed through the iconography of blaxploitation regardless of the narrative content of the film. This meant that films with predominantly black casts and/or themes surrounding race were seen at the time as occupying the same discursive space. At a time when African Americans’ battle with oppression heightened, and worsening city problems were evident, films that celebrated overcoming The Man were empowering and enjoyable. (Acham p.114) While many 1970s black-themed films were using limited black talent, The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1971), not only boasted a black cast, but black director Ivan Dixon and black writer Sam Greenlee. Greenlee, a Chicagoan who experienced racism firsthand while in the military, and while stationed in Iraq, found kinship with the oppressed Iraqis under the British and US backed monarchy, wrote The Spook which he then adapted as a screenplay for Dixon’s film.

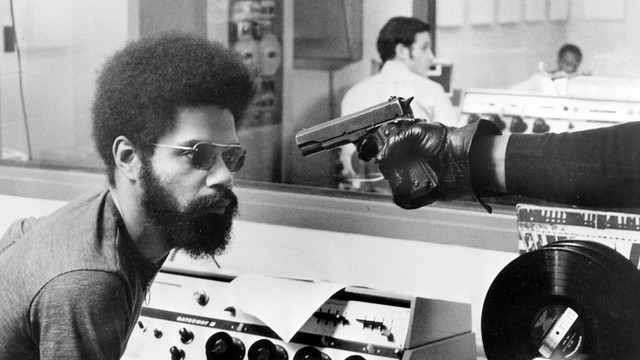

On the surface, The Spook Who Sat by the Door looks like any other blaxploitation film. There’s the man who says things like, “those people make great athletes,” and “This is no place for misplaced cotton pickers.” There’s judo, there is Black militancy, there’s prostitute and there’s that offensive title. “Spook” here has a double meaning, spy, and a derogatory term to address an African American. But the film is much more radical than that. Taking advantage during the integration era, a black man named Don Freeman, patiently works up the ranks as a token black CIA agent, learning everything he could while being a model employee and in turn use all the knowledge, he acquired into an urban armed guerrilla warfare in his native Chicago against authorities. By the end, the film advocates armed uprising by the disenfranchised blacks in every major city in America. Despite the success of the film’s opening gross of half a million dollars in the first three days, the film was pulled from theaters and shelved.

On the surface, The Spook Who Sat by the Door looks like any other blaxploitation film. There’s the man who says things like, “those people make great athletes,” and “This is no place for misplaced cotton pickers.” There’s judo, there is Black militancy, there’s prostitute and there’s that offensive title. “Spook” here has a double meaning, spy, and a derogatory term to address an African American. But the film is much more radical than that. Taking advantage during the integration era, a black man named Don Freeman, patiently works up the ranks as a token black CIA agent, learning everything he could while being a model employee and in turn use all the knowledge, he acquired into an urban armed guerrilla warfare in his native Chicago against authorities. By the end, the film advocates armed uprising by the disenfranchised blacks in every major city in America. Despite the success of the film’s opening gross of half a million dollars in the first three days, the film was pulled from theaters and shelved.

Herbie Hancock, a pianist, keyboardist, and composer extraordinaire, first rising to prominence as a pivotal figure of the post-bop jazz movement of the 1960s, most notably through collaboration with Miles Davis’ incredible Second Quartet, continued to innovate, boldly embracing new technologies and new approaches in music. His keen interests in crossover appeal of jazz with soul, R&B, and funk, went on to become one of the most well-known and popular composers in American music. It was Italian film director Michelangelo Antonioni’s first English language feature film, Blow-Up (1966) that Hancock provided music for its soundtrack for the first time. Antonioni, a big jazz fan, knew Hancock’s music. The film, reflecting the decadence and excess of the decade, was perfectly accompanied by Hancock’s groovy, percussion heavy soundtrack. And like many of his compositions, “Bring Down the Birds” from the Blow-Up soundtrack would be sampled and enjoy a second life in the 90s in Deee Lite’s “Groove is in the Heart (1990).”

His seventh album The Prisoner (1969) was dedicated to the Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. who was assassinated the year before, the album and many of the songs on it reflect African American experience at the time. The most beautiful and delicate composition in the album is the first track I Have a Dream, invoking MLK’s famous speech at the steps of Lincoln Memorial in 1963, featuring a haunting flute by flutist Herbert Laws. This was the last album Hancock made with the legendary jazz label, Blue note. The second film he scored was The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1971). Dixon and Hancock met on the set of Hogan's Heroes (1965-71), an American TV sitcom, where Dixon played Staff Sergeant Kinch. Dixon knew his music and asked him to compose the soundtrack.

At the time of their collaboration, Hancock’s was moving on to something different. He signed with Warner Brothers Music and made forays into popular music including composing many jingles for TV commercials and Bill Cosby’s animated TV special Hey, Hey, Hey, It’s Fat Albert (1969). Musically, Hancock was going through his Mwandishi phase. It was his first departure from the traditional idioms of jazz, as well as the beginning of original and creative style which eventually appealed to a wider audience. Mwandishi means composer in Swahili, the name he chose for himself in the late 1960s to early 70s. Mwandishi (1971) happens to be the name of his 9th studio album. Albums he produced between 1969 - 1973 are now known as the work of Hancock’s Mwandishi period. Deeply influenced by Miles Davis’ foray into electronic music and working on In a Silent Way (1969) and Bitches Brew (1970) with the master trumpeter, he began to experiment with combining electronic with acoustic instruments during this period. Along with his Mwandishi albums, the soundtrack of The Spook marks the jazz pianist’s move from a straighter jazz sound to funk and a transition that would reach its apex with 1983’s “Rock It!” A hit single featured in his album Future Shock (1983) using scratching, drum machines and synthesizers, confounded jazz critics, set the blueprint for rap and much of the pop music for the coming years. Including dialog and sound from the film, the soundtrack is an important precursor to modern film soundtracks. Hancock worked on about ten soundtracks since then, most notably, Death Wish (1974), A Soldier’s Story (1984), Around Midnight (1986), Colors (1988) and Harlem Nights (1989). As an educator, Hancock influenced countless young talents over the years as a chair and an artistic director of Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz at USC.

Unlike Ivan Dixon’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door which fell into obscurity after it opened and only to be rediscovered with the proliferation of home videos and streaming much later on, Gordon Parks Jr.’s Super Fly (1972) was a bona fide hit, grossing more than 4 million dollars at the box office. A film about a suave cocaine dealer, Super Fly has many of the negative stereotypes the blaxploitation genre was accused of perpetuating - pimps, hustlers, degradation of women, violence, and drug use. Youngblood Priest (Ron O’Neal), a tall, handsome black man with long flowing black hair and hyper fashionable attire with a big car and beautiful white and black girlfriends, lives a luxurious lifestyle in Harlem. He is a man of action and a ruthless boss. No one rips him off and everyone has to pay. But with all the money he is generating selling drugs, he still yearns to go straight. With his partner Eddie, he is trying to score big one last time before he retires from the drug business. The plan is, with $300,000 he and Eddie have, to buy 30 kilos of high-quality cocaine and turn it around for one million, split between them and get out of business. Eddie, although going along with the plan, is unsure. For him, dealing drugs is the only option left to them by “the Man”. After their goon, Freddie, gets killed by the police, they find out that it is the deputy police commissioner Reardon’s intention to keep them in the game and in his pocket. Although Eddie likes the idea of police protection and continuing being the drug dealer, Priest is his own man and no one else can have power over his life. After his mentor, Scatter, who helped him start the business, feeds him the information on the Reardon before he gets killed by the police, Priest devises a plan to escape the drug underworld clean with a big middle finger to the corrupt system.

Unlike Ivan Dixon’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door which fell into obscurity after it opened and only to be rediscovered with the proliferation of home videos and streaming much later on, Gordon Parks Jr.’s Super Fly (1972) was a bona fide hit, grossing more than 4 million dollars at the box office. A film about a suave cocaine dealer, Super Fly has many of the negative stereotypes the blaxploitation genre was accused of perpetuating - pimps, hustlers, degradation of women, violence, and drug use. Youngblood Priest (Ron O’Neal), a tall, handsome black man with long flowing black hair and hyper fashionable attire with a big car and beautiful white and black girlfriends, lives a luxurious lifestyle in Harlem. He is a man of action and a ruthless boss. No one rips him off and everyone has to pay. But with all the money he is generating selling drugs, he still yearns to go straight. With his partner Eddie, he is trying to score big one last time before he retires from the drug business. The plan is, with $300,000 he and Eddie have, to buy 30 kilos of high-quality cocaine and turn it around for one million, split between them and get out of business. Eddie, although going along with the plan, is unsure. For him, dealing drugs is the only option left to them by “the Man”. After their goon, Freddie, gets killed by the police, they find out that it is the deputy police commissioner Reardon’s intention to keep them in the game and in his pocket. Although Eddie likes the idea of police protection and continuing being the drug dealer, Priest is his own man and no one else can have power over his life. After his mentor, Scatter, who helped him start the business, feeds him the information on the Reardon before he gets killed by the police, Priest devises a plan to escape the drug underworld clean with a big middle finger to the corrupt system.  The film struck a core with black youth film goers and became a cultural phenomenon. It also resonated with the post-Civil Rights Movement generation of African Americans, who saw Youngblood as a new example of how to rise in the American class system. Super Fly’s focus on black underground wealth generation was energized by its rejection of the two classic protest strategies of integration and transformation- the film spoke to disillusionment with both racially ameliorative civil rights politics and radical black nationalism. (Quinn, p.88) Classic civil rights mobilization was based upon those who worked hard at honest callings, whatever their origins, could better themselves and lift their children’s prospects. By romanticizing black criminal life, Super Fly was detrimental to their cause. In one pivotal scene, three “black militants” approach Priest and Eddie and challenge them to give something back to the community. “It is time for you to pay some dues!” Priest responds, “Unless you start killing some whitey, go sing your marching songs somewhere else.” In its staging of business dynamism outside of mainstream white structures, Super Fly proved extremely attractive in a hardening sociopolitical climate. Priest can be seen as a self-made African American outlaw entrepreneur, determined to transcend the endless cycle of crime and danger to which “the Man” has conscribed him, and smart and tough enough to succeed.

Curtis Mayfield was a singer, lyricist and record producer who started his career in a vocal group The Impressions. It was his socially conscious lyrics that made such songs as “Keep on Pushing (1964)” and “People Get Ready (1965)” being embraced by the Civil Rights leaders and utilized during the decades’ many freedom rides, that elevated Mayfield from soul group member to poet/artist/activist.

The film struck a core with black youth film goers and became a cultural phenomenon. It also resonated with the post-Civil Rights Movement generation of African Americans, who saw Youngblood as a new example of how to rise in the American class system. Super Fly’s focus on black underground wealth generation was energized by its rejection of the two classic protest strategies of integration and transformation- the film spoke to disillusionment with both racially ameliorative civil rights politics and radical black nationalism. (Quinn, p.88) Classic civil rights mobilization was based upon those who worked hard at honest callings, whatever their origins, could better themselves and lift their children’s prospects. By romanticizing black criminal life, Super Fly was detrimental to their cause. In one pivotal scene, three “black militants” approach Priest and Eddie and challenge them to give something back to the community. “It is time for you to pay some dues!” Priest responds, “Unless you start killing some whitey, go sing your marching songs somewhere else.” In its staging of business dynamism outside of mainstream white structures, Super Fly proved extremely attractive in a hardening sociopolitical climate. Priest can be seen as a self-made African American outlaw entrepreneur, determined to transcend the endless cycle of crime and danger to which “the Man” has conscribed him, and smart and tough enough to succeed.

Curtis Mayfield was a singer, lyricist and record producer who started his career in a vocal group The Impressions. It was his socially conscious lyrics that made such songs as “Keep on Pushing (1964)” and “People Get Ready (1965)” being embraced by the Civil Rights leaders and utilized during the decades’ many freedom rides, that elevated Mayfield from soul group member to poet/artist/activist.

In 1970 Mayfield went solo and released Curtis (1970) and Roots (1971). With songs such as “The Other Side of Town,” “We the People Who are Darker than Blue,” and “Move on Up," he continued to show that he was acutely aware of America’s racial, and class divide and was not afraid to discuss it.

Recorded in just three days, the soundtrack made an indelible mark on pop consciousness. Blaxploitation films had opened an ancillary market for black musicians. Earth Wind and Fire perform the music for Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Isaac Hayes did Shaft (1971) and Marvin Gaye did Trouble Man (1972). Now it was Mayfield’s turn.

In Super Fly soundtrack, Mayfield continued to offer his social commentary. For James Stewart in his article Message in the Music, it was a deliberate attempt to neutralize the thematic content and visual imagery by producing audio commentaries challenging the glorification of the underground economy. “In effect, these cultural warriors engaged in a type of guerrilla campaign against external cultural manipulation. (Stewart p.211)

The first single from the soundtrack, which was released just before the film hit the theaters, “Freddie’s Dead,” was a massive hit and sold more than a million copies. Freddie, a good-hearted yet weak willed man caught up in the life of a pusher, is killed unceremoniously in the film. Mayfield eulogizes this side character this way:

Everybody's misused him, ripped him up and abused him. Another junkie plan, pushin' dope for the man. A terrible blow, but that's how it goes. If you don’t try, you’re gonna die. Why can’t we brothers protect one another? No one’s serious, and it makes me furious, Don’t be misled, just think of Fred.

Mayfield was by far the best-remunerated African American on the project. Earnings from performance rights and royalties feld back to Mayfield because he owned his own publishing company and independent record label, Curtom Records, founded in 1963. The hit singles “Super Fly'' and “Freddie’s Dead” both sold more than one million copies, and the crossover soundtrack album went on to shift a colossal twelve million units. Mayfield ultimately earned more than $5 million for his soundtrack. (Quinn p.89)

After the critical and financial success of Super Fly,” Mayfield went on to score several more blaxploitation soundtrack albums: Claudine (1974), Let’s Do It Again (1975), Sparkle (1976), Short Eyes (1977) and A Piece of Action (1977).

Riding the tide of blaxploitation boon in the early to mid 70s, many of the prominent African American musicians from different genres and backgrounds were given the opportunity to collaborate and explore their craft and artistry to not only reflect the changing society but to help shape and sway African American youth to let themselves heard and protest the Civil Rights Movement’s unkept promises. Herbie Hancock lend his name and music to a radical, revolutionary black film while continuing his exploration of electronic music and found his way to a wider audience, working with different musicians and filmmakers. For Mayfield, while making a cultural milestone with a blaxploitation film soundtrack, he was afforded to counterbalance the negative reaction to the film with his activist lyrics.

Bibliography

Guest, Hayden. “Soundtrack by Herbie Hancock. Harvard Film Archive.” (February 2014). https://harvardfilmarchive.org/programs/soundtrack-by-herbie-hancock

Quinn, Eithne. “‘Tryin’ to Get Over’: ‘Super Fly’, Black Politics, and Post—Civil Rights Film Enterprise.” Cinema Journal 49, no. 2 (2010): 86–105.

Telotte, J.P. “The New Hollywood Musical: From Saturday Night Fever to Footloose.” In Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, ed. Stephen Neale, London: Bloomsbury (2001): 48-61.

Ryfle, Steve. “The Politics of Super Fly: The Blaxploitation Classic That Defined an African-American Battle for Self-Determination on Screen.” Cinéaste 44, no. 2 (2019): 12–16.

Stafford, James. “From the Stacks: Herbie Hancock- The Spook Who Sat by the Door.” Why It Matters. (August 25, 2015). https://wimwords.com/2015/08/23/from-the-stacks-herbie-hancock-the-spook-who-sat-by-the-door/

Stewart, James B. “Message in the Music: Political Commentary in Black Popular Music from Rhythm and Blues to Early Hip Hop.” The Journal of African American History 90, no. 3 (2005): 196–225.

Yaquinto, Marilyn. “Cinema as Political Activism: Contemporary Meanings in The Spook Who Sat by the Door.” Black Camera 6, no. 1 (2014): 5–33. https://doi.org/10.2979/blackcamera.6.1.5.