Multiplicity in Ceaseless Motion: Black Performativity in Chameleon Street and Suture

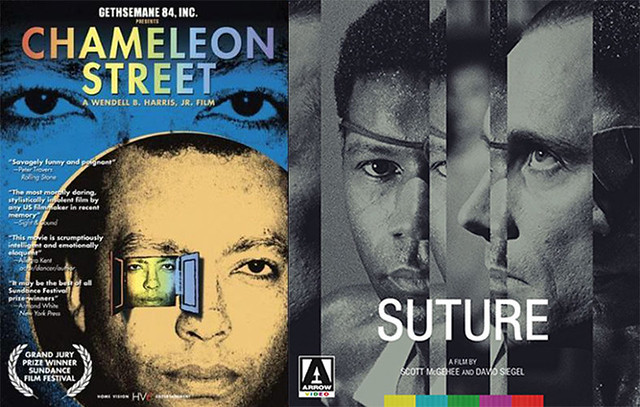

My research project is on Wendell Harris’s Chameleon Street and Scott McGehee & Brian Siegel’s Suture. Both films explore Black performativity in strikingly original ways, contrasting and challenging the typical notion of how African American lives are portrayed in American cinema. They examine how Black identity is viewed and practiced in the confines of the white hegemonic world and conclude that evasiveness and fluidity of blackness are very much a part of what constitutes performative Black identity.

My research project is on Wendell Harris’s Chameleon Street and Scott McGehee & Brian Siegel’s Suture. Both films explore Black performativity in strikingly original ways, contrasting and challenging the typical notion of how African American lives are portrayed in American cinema. They examine how Black identity is viewed and practiced in the confines of the white hegemonic world and conclude that evasiveness and fluidity of blackness are very much a part of what constitutes performative Black identity.

Based on a real life story of William Douglas Street Jr., Chameleon Street is about an African American man who compulsively takes on different identities to satiate the needs of others as well as his. The film explores Black performativity in contemporary American society and how it deviates from many stereotypical, binary notions of blackness. I will make an argument that Chameleon Street demonstrates the constantly shifting Black identity based on performativity- rebellious and non-conforming, makes a truer Black identity.

The film starts with a prison counselling session with Street and a white psychiatrist. The psychiatrist asks what Street is going to do once he is released from prison. Street says no more impersonations. Then the psychiatrist tells him, matter of factly, that he does not believe him. Street retorts, “Would I lie?” The psychiatrist says

that he doesn’t think Street is necessarily lying, but he is not in control of what he does or says that his behavior is complementary. Then he asks Street if he understands what he means by that. Street says no. The psychiatrist then explains that he intuits the needs of others and fills those needs. But at this point, Street’s attention is already elsewhere. After contrasting colors, jump cuts and indecipherable whisperings, Steet’s narration continues, “I think the air is sweet. I know not what I am. I am Chameleon Street.” From the beginning, Street flatly refuses to engage and reveal his true identity if there was one.

W.E.B. Du Bois, a prominent African American author and civil right activist, was the first scholar to invoke the notion of “double consciousness” when talking about Black lives in America. In his article “Strivings of the Negro People,” in 1897, he explained the predicament many African Americans face in post-Civil War American society:

W.E.B. Du Bois, a prominent African American author and civil right activist, was the first scholar to invoke the notion of “double consciousness” when talking about Black lives in America. In his article “Strivings of the Negro People,” in 1897, he explained the predicament many African Americans face in post-Civil War American society:

…born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American World, - a world which yields him no self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One feels his two-ness, - an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, - this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost.

With Du Bois’s invocation of double consciousness and the longing for merging two souls into a better truer self as a framework, I will attempt to define performative Black identity in Chameleon Street.

Doug Street’s con: passing as professionals - a reporter, doctor and lawyer has its roots in racial passing in cinema, made famous by Imitations of Life, (1934 version, directed by John M. Stahl and 1959 version directed by Duglass Sirk) and as well as in literature, Passing. (written by Nella Larson) Racial passing occurs when a person of color or of multiracial ancestry who assimilated into white majority to escape the legal and social conventions of racial segregation and discrimination. Even though the tone of his skin is never discussed in the film, Wendell Harris, who directs and also plays Street is undoubtedly an African American man. The classic passing narrative is replete with the familiar and tragic melodies of passing as betrayal, blackness as self-denial, whiteness as comfort. Chameleon Street deviates from this classic passing and concentrates it on its ‘performance’ side of it. After all, passing is a performance that, like any other, requires an audience.

The real Doug Street whose life the film is based on is said to have made no more than $4,000 dollars from his shenanigans. So it wasn’t just the financial gain he was after. Street masquerading as a doctor, journalist, Ivy League school student and lawyer is, according to Michael Gillespie, an act of rebellion infiltrating the exclusive zone of elite professional castes kept out of the practical reach, and aspiration of most black men. Being as a raced passer, Street is compelled by a desire to be convincing, successful, and exceptional. Gillespie also states that Street exemplifies what Elaine Ginsberg describes as the dialectical nature of passing: “Passing is about identities: their creation or imposition, their adoption or rejection, their accompanying rewards or penalties. Passing is also about the boundaries established between identity categories and about the individual and cultural anxieties induced by boundary crossing. Finally, passing is about specularity: the visible and the invisible, the seen and the unseen.”

In Passing, Irene, a childhood friend of Clare, the protagonist of the book who ‘race passes’ in white society, observes that it’s not only financial freedom that Clare strives for passing as white. It’s also “stepping always on the edge of danger,” that she revels in the nearness of getting caught. Gillespie notes that Street “thrives as a proficient quarreling with the power, privilege, and regulation of boundary crossing as Chameleon Street depicts the strategic opportunities generated by the discounting of the immanence of identity categories.” Combining this with borrowing Judith Butler’s notion of gender as performativity in her essay, Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory, where she states that gender is performative means that there can be no gender identity before the gendered acts, because the acts are continuously constituting the identity. Substituting gender with race, Chameleon Street gives a new perspective into the performative identity of African American entertainers since the beginning of the moving picture industry, going all the way back to mammy roles and slow-talking, lazy bum roles in often grotesquely negative stereotypes.

When talking about Stepin Fechit, a vaudeville performer who made many ‘show stealing’ appearances in Hollywood films in the 1930s, known for his slurring speech and somnambulistic simpleton behavior, Miriam Petty asserts the phrase, ‘stealing the show,’ as informed by Frederick Douglass and Andrew Levine, and others, to indicate theft as an act of survival and protest. After the grossly racist misrepresentation of an African American male in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, many prominent African American scholars and thinkers at that time, called for the positive representations of Blacks in the uplift movement. The most prominent figure in uplift cinema and race films (films made by and for Black audiences), was Oscar Micheaux, who made more than 40 films in his career. But even his major film Body and Soul, which introduced young Paul Robeson (in a dual role, no less), to cinema, wasn’t immune to criticism over its representation of Black criminality. Micheaux argued that realism, not some false idyll, was the key to progress of the race. In her book Double Negative, Raquelle J. Gates argues that the power of the negative image rests in its ability to shift the dynamics in popular culture. The reverberations of negative texts function as tremors that irrevocably weaken the foundation on which their positive counterparts are constructed. Street went in and out of jail for his shenanigans, ranging from extortion, mail fraud, identity theft and impersonation. In the eyes of the law, he was nothing but a low level criminal. But it’s that negativity - the act of coning, stealing (identity), in the context of strategic essentialism, is to learn from it.

When talking about Stepin Fechit, a vaudeville performer who made many ‘show stealing’ appearances in Hollywood films in the 1930s, known for his slurring speech and somnambulistic simpleton behavior, Miriam Petty asserts the phrase, ‘stealing the show,’ as informed by Frederick Douglass and Andrew Levine, and others, to indicate theft as an act of survival and protest. After the grossly racist misrepresentation of an African American male in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, many prominent African American scholars and thinkers at that time, called for the positive representations of Blacks in the uplift movement. The most prominent figure in uplift cinema and race films (films made by and for Black audiences), was Oscar Micheaux, who made more than 40 films in his career. But even his major film Body and Soul, which introduced young Paul Robeson (in a dual role, no less), to cinema, wasn’t immune to criticism over its representation of Black criminality. Micheaux argued that realism, not some false idyll, was the key to progress of the race. In her book Double Negative, Raquelle J. Gates argues that the power of the negative image rests in its ability to shift the dynamics in popular culture. The reverberations of negative texts function as tremors that irrevocably weaken the foundation on which their positive counterparts are constructed. Street went in and out of jail for his shenanigans, ranging from extortion, mail fraud, identity theft and impersonation. In the eyes of the law, he was nothing but a low level criminal. But it’s that negativity - the act of coning, stealing (identity), in the context of strategic essentialism, is to learn from it.

A pun on Cathasian sense of being, Street famously says “I think, therefore I scam.” in his narration. Gillespie notes , “Mercurial, unstable, and improvisational, Street as intuitionist encounters the Cartesian ideal with a black consciousness devoted to self-evident truth as performative.” The statement shares an affinity with another subterranean utterance, “I am an invisible man.” Ralph Ellison’s novel, The Invisible Man, is about an unnamed black narrator experiencing racism and being an outcast through a tumultuous period of American history, and ends up a shaded trickster to adapt to white society at the cost of his own identity. It is the story of a black man in America who doesn’t need a disfigured face or one hidden behind bandages to be spurned and treated as less than a man. “That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact,” explains Ellison’s nameless narrator, “a matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality.” The color of his skin renders him unseen in the mind’s eye of the somnambulist whites who have been taught to categorize him as outside of importance, to discount not just his equality but his humanity. In it, the shape-shifting saboteur Reinhart, more of an idea than a real character, whom unnamed narrator is often mistaken for, is the perfect foil for Gillespie to illustrate the effects of Street’s performance:

A pun on Cathasian sense of being, Street famously says “I think, therefore I scam.” in his narration. Gillespie notes , “Mercurial, unstable, and improvisational, Street as intuitionist encounters the Cartesian ideal with a black consciousness devoted to self-evident truth as performative.” The statement shares an affinity with another subterranean utterance, “I am an invisible man.” Ralph Ellison’s novel, The Invisible Man, is about an unnamed black narrator experiencing racism and being an outcast through a tumultuous period of American history, and ends up a shaded trickster to adapt to white society at the cost of his own identity. It is the story of a black man in America who doesn’t need a disfigured face or one hidden behind bandages to be spurned and treated as less than a man. “That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact,” explains Ellison’s nameless narrator, “a matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality.” The color of his skin renders him unseen in the mind’s eye of the somnambulist whites who have been taught to categorize him as outside of importance, to discount not just his equality but his humanity. In it, the shape-shifting saboteur Reinhart, more of an idea than a real character, whom unnamed narrator is often mistaken for, is the perfect foil for Gillespie to illustrate the effects of Street’s performance:

Like Rinehart, Street embodies multiplicity in ceaseless motion, undermining every certitude, destabilizing every authority, concealing the ‘truth’ of his character by performing its proliferation in public. Thus the skilled racings or stagnings of race by Street as a black cipher of “myth and dash, being and non-being,” exceed allegiances or determinacy. Charmeleon Street executes Rinehartism in a cinematic key as it is crucially guided by an immaculate abandon and liquidity exemplified by Street’s exploits.

Far from not knowing what he is, Street knows exactly what he is doing in subsequent talk with the same psychiatrist in the later part of the film- conning white people. He lets whites believe in correctly analyzing this complex, exotic, “notorious negro”. He goes on to say that when he meets somebody, he knows in the first few minutes who they want him to be and he just cut the emotional cloth of his personality to fit the emotional clothing of whoever he is...conning. Raced functions as a term for Street’s modulating acts of identity as a measured motion or rhythm that is affectively attuned to place, race and being. This is because Chameleon Street insists on a shift from racial fidelity to identitarian disloyalty, racial passing to racial performativity. In other words, Chameleon Street as an enactment of film blackness demonstrates process rather than the idle cataloguing of lack or pathology.

Scott McGehee and Brian Siegel’s Suture is another prime example in examining class, Black identity & Black performativity in noir thriller setting.. In a clever word play, suture, in film terms, is an editing technique to make the audience forget the presence of the camera and situate them inside a film. In the film, the disfigured amnesiac protagonist, who survives a car bomb blast which was made like suicide in an attempt to evade a murder charge, goes through multiple reconstructive surgery on his face (hence the need for suture), only to look exactly the same as before, except for an eye patch. The main conceit of Suture is that the brothers Vincent and Clay, who are supposed to be similar in appearance (similar enough for one to plot the murder of the other and take over his brother’s identity), are played by one white (Michael Harris) and one black (Dennis Haysbert) actor. The filmmakers and audience are in on the joke, but not the people who inhabit the world within the film. They see two white men. Unlike Chameleon Street, here, the embodied black experience is artificially accentuated. The black body, played by the statuesque Haysbert, is highlighted in his otherwise all white environment. His visible invisibility is an obvious metaphor for Blackness. The amnesiac who only remembers his past only in flashes and symbolic dreams - a former life as a poor construction worker in the rural south. He ultimately recovers his memories when confronted with his doppelganger Vincent, who came back to finish the job of killing him. After the confrontation and ending up killing Vincent, he decides to renounce his past and choose to continue to live in his relatively newfound opulence and privilege in performative identity.

Scott McGehee and Brian Siegel’s Suture is another prime example in examining class, Black identity & Black performativity in noir thriller setting.. In a clever word play, suture, in film terms, is an editing technique to make the audience forget the presence of the camera and situate them inside a film. In the film, the disfigured amnesiac protagonist, who survives a car bomb blast which was made like suicide in an attempt to evade a murder charge, goes through multiple reconstructive surgery on his face (hence the need for suture), only to look exactly the same as before, except for an eye patch. The main conceit of Suture is that the brothers Vincent and Clay, who are supposed to be similar in appearance (similar enough for one to plot the murder of the other and take over his brother’s identity), are played by one white (Michael Harris) and one black (Dennis Haysbert) actor. The filmmakers and audience are in on the joke, but not the people who inhabit the world within the film. They see two white men. Unlike Chameleon Street, here, the embodied black experience is artificially accentuated. The black body, played by the statuesque Haysbert, is highlighted in his otherwise all white environment. His visible invisibility is an obvious metaphor for Blackness. The amnesiac who only remembers his past only in flashes and symbolic dreams - a former life as a poor construction worker in the rural south. He ultimately recovers his memories when confronted with his doppelganger Vincent, who came back to finish the job of killing him. After the confrontation and ending up killing Vincent, he decides to renounce his past and choose to continue to live in his relatively newfound opulence and privilege in performative identity.

A psychiatrist, Dr. Yoshida (who is non-white, non-black therefore neutral) who narrates Suture, concludes that the amnesiac chose to erase the wrong past. That he will never be happy because he is a pretender. He won’t? What if the performances themselves are true identities? Although Suture is subservient to typical good/bad dichotomy at the end, the film demonstrates the performativity of the black body alone in the eyes of others.

The driving tenor of both Chameleon Street and Suture obviously considers the substance of blackness in ways not dependent on self dispossession because Street and Clay as film protagonists don’t exhibit any interest in the disavowal of blackness for the lure of whiteness. There is an underlying contempt for whitness in Street and Clay’s performative impulse and their sense of cool detachment in their performances. But both films highlight the black desire in attaining white privilege through performances. They distinctly amplify the way racial passing potentially displaces the relationship between inside and outside, truth and appearance, identity and identity politics.

As it is demonstrated in both Chameleon Street and Suture, the process of Black performativity defies and disrupts the society’s compulsive need for identity while refusing to be pinned down. For both films, Ellison’s concept, “To be invisible is to be seen, instantly and fascinatingly recognized as the unrecognizable, as the abject, as the absence of individual self-consciousness, as a transparent vessel of meanings wholly independent of any influence of the vessel itself.” is figuratively and literally presented. The last image of Chameleon Street is Street standing against the jail cell bars, back lit and his face obscured by cigarette smoke - like a smoke screen, remaining indisciperable and unknowable, only leaving trails of his shenanigans in his performative false identities. In Suture, Clay, free in the eyes of white society presented in the film, conceals his blackness with an invisible wink, willfully assuming that false identity as his own.

The act of performing multiple roles continuously in the white hegemonic society as an African American, is a series of delicate socio-political, cultural negotiation. It’s the process rather than the idle cataloguing of lack or pathology. It’s an act of defiance and survival.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Du Bois, W.E.B. “Strivings of the Negro People.” The Atlantic Monthly, August 1897 https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1897/08/strivings-of-the-negro-people/305446/

Butler, Judith. "Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory." Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988): 519-31.

Field, Allison Nadia. Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity. Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2015.

Gates, Raquelle J. Double Negative: The Black Image and Popular Culture. Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2018.

Gillespie, Michael Boyce. Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film. DURHAM; LONDON: Duke University Press, 2016.

Hahn, Andrew. “Color-Blind in Black and White: How Suture Wants Us to Ignore Race.” Bright Lights Film Journal, July 2020 https://brightlightsfilm.com/color-blind-in-black-and-white-how-suture-wants-us-to-ignore-race/#.YKMiFpNKjUp

Petty. Miriam J. Stealing the Show: African American Performers and Audiences in 1930s Hollywood. University of California Press, 2016. Rottenberg, Catherine. ""Passing": Race, Identification, and Desire." Criticism 45, no. 4 (2003): 435-52.