In celebration of Abbas Kiarostami Retro at IFC Center starting this weekend, I present you something I wrote about the master a while ago. Please visit IFC website for schedule

Abbas Kiarostami, an Iranian master filmmaker, painter, photographer, and poet, passed away from gastrointestinal cancer in Paris in 2016. As an avid fan of his humanistic, genre transcending films, I can say with a certain conviction that we've lost one of the greatest artists in the world of cinema.

My introduction to Iranian cinema came when a good friend of mine introduced me to Mohsen Makhmalbaf's films (on bootlegged VHS). Soon I was enamored by anything Iranian. It was a spur of the moment decision that led me to check out The Wind Will Carry Us in theaters in 2000, not knowing anything about the film other than it being from Iran. And what an experience it was! Its elegant simplicity and great eye for landscapes impressed me greatly. Seeing Wind Will Carry Us (1990) was also a watershed moment in my cinematic education. I’ve never seen such a truthful observation of human life before and it made me a life long devotee of his work. What's most striking about Kiarostami’s artistry is his effortless, seamless quest for truthful representation of human conditions on film. Whether they are shot on 35mm or with a consumer grade handy-cam, the inquisitive interactions of non-actors with their natural dialogue often imply that there is no real distinction between cinema and reality.

It was Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry, winning the Palme d'Or at Cannes Film Festival in 1997 that introduced his poetic, meta-fictional cinema to the world and put many of his contemporaries on the world cinema map. And yet, when the director first burst onto the world cinema stage, critics didn't know what to make of his films: Roger Ebert gave Taste Of Cherry one star, calling it “excruciatingly boring” (Ebert, Taste of Cherry Review, RogerEbert.com,1998), while Jonathan Rosenbaum desperately tried to find some sort of reference in Western cinema tradition in his films by comparing Godard’s early work to Kiarostami’s in terms of reflecting society in certain periods or suggesting the similarities between Close-Up and John Guare’s play Six Degrees of Separation which later was adapted into a film. (Rosenbaum, 2001, 2) But as Kiarostami himself says in 10 on Ten (2004), a documentary on his reflection on the techniques he used on his 2001 film, Ten, he believes that simply showing austere reality with an open ending can entice audiences to reflect on their own lives. I can't think of a higher compliment to the audience than what Kiarostami bestows upon us with his films.

Kiarostami’s main themes throughout his filmography are Children facing and overcoming harsh reality, Time Passing/Fleeting Nature of Human Existence, and the Perceived Notion of Truth and Reality. His observations of children, for example, date back to 1970s when he helped establish the filmmaking department at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) in Tehran. There he made a series of documentaries and shorts concerning school children. Kiarostami's depiction of children, from his Kanun days (The Bread And The Alley, Break time, The Traveler) to later films (The Koker Trilogy, ABC Africa, Ten) is that of a nondisciplinarian in that he simply observes children being children. Often, these films are about children facing harsh reality (Soltani, The Child Heroes of Abbas Kiarostami’s Films, Movie Mezzanine, 2016). In his feature documentary, Homework (1989), for example, it is obvious that the educational system in Iran is too strict and puts a lot of pressure on children, both in school and at home. It's revealing that all the children interviewed for the film know what “punishment” means but don't know the meaning of the word “praise.” Parents, as well, say that the system is too harsh on the children; that it kills their creativity and ends up producing a generation of mindless drones. The director seems to be agreeing with this sentiment: “I tried to look at the world from a child’s point of view” (Jones, Children of the Revolution, Guardian, 2000).

Children facing harsh reality is the theme of his films, later known as the Koker Trilogy. Kiarostami made three films set in Koker village in Gilan Province, an area of Northern Iran lying along the Caspian Sea. Where is Friend’s Home? (1987) was the first of the three, and is about a boy trying to deliver a notebook that belongs to a friend who lives in the next village. The second one, Life and Nothing More… (1992), was made after the devastating earthquake in 1990. A middle aged man and his young son are on the road to Koker, a northern rural village leveled by the devastating earthquake. They spend most of the film's running time in their car. It is only revealed later on that the man is a film director (a Kiarostami stand-in) who is looking for a child actor who starred in his previous film, Where Is Your Friend's Home? Through The Olive Tree (1994), completes the trilogy. A fictional 'making-of' Life And Nothing More, the film is a beautiful film that shows resilience of children after a life altering disaster.

From the bustling bottleneck traffic of Tehran in The Report (1977) to Ten (2002), Kiarostami’s films remind us that life with its ebbs and flows is never stopping and always changing. This is never as apparent than in his masterpiece, Taste of Cherry. Inquisitive dialog scenes, just like intimate questionnaires in documentaries, are staged usually in moving cars (and after Taste of Cherry, interior driving scenes became synonymous with Kiarostami’s films). The beauty of Taste of Cherry lies in its simplicity: a man drives around looking for someone to assist him in his suicide. They don't have to do the deed; he will take sleeping pills and lie down in an already dug up grave. In the morning, they can put some earth on him if he's dead and they will be rewarded handsomely for doing so. First, a young soldier runs away after finding out what the man is up to. Second, a seminary student from Afghanistan objects because of his religious beliefs and tries to dissuade him. And finally, an old taxidermist agrees to it, because he has a sick child. He tells the suicidal man that he too, contemplated committing suicide. Adding that he abandoned the idea after tasting cherries.

Kiarostami reminds us that we are watching a film throughout Taste of Cherry; for example, he inserts the footage of himself shooting the film into the narrative. The nameless protagonist does not exist in real life, that his moral quandary is an invitation for us to mull over. It’s Kiarostami himself who is asking us these questions directly. What makes him contemplate such thoughts? What would you do if you were asked to help him kill himself? With Louis Armstrong's St. James’s Infirmary Blues, a song usually associated with funerals, playing at the end over the image, he tells us that death is inevitable for all of us, and it makes us contemplate our own mortality. If the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky tried to make us feel the 'passage of time' with his virtuosic creeping camera dolly movements, framing and lighting, Kiarostami succeeds in astounding simplicity, in one hour and forty minutes- Life is a moving car. Done. The impact is still immense. It all fits nicely with his theme of life, death, blurring boundaries of cinema and reality.

Kiarostami draws from many aesthetic sources. His admiration for Japanese culture, for example, can be seen in his haiku style poems and in Like Someone in Love (2014), which was set in Japan with Japanese cast. In an interview he said:

I am certain that my fascination with Japan has been with me forever, even before I got to go to Japan. Even my very first attempt at any kind of artistic expression, which were poems that I wrote when I was 20 years old, resemble haiku. I had no idea at the time, but I wrote poems that are very like haikus. And in my photography work, there are some kind of common forms found in traditional Japanese paintings. There is some sort of resonance in my practice and Japanese art. So there has always been real interests before my first visit there which was confirmed whenever I went back thereafter. I've been visiting Japan periodically over 20 years now. (Chang, We Are All the Same: Abbas Kiarostami Interview,Screen Anarchy 2013)

The influence of Japanese cinema is evident in Five (2003), in which Kiarostami pays homage to Yasujiro Ozu. The film consists of five segments set in a coastal area in Iran without any characters or dialogue. With zen-like simplicity, we are presented with five static shots of various lengths. The camera remains static, but birds, dogs and people are heard and seen, in and out of the frame. With each long take we observe nature and human existence for what they are. In the final part of Five, Kiarostami traces the reflection of the moon on the surface of a pond. We don’t really understand what we are watching for a while. It’s dark, and the black and white image is grainy. We then realize that it’s the reflection of the moon on water as it ripples from time to time. We watch it with the chorus of insects in its nighttime surroundings to the breaking of dawn. This entrancing, collective cinematic experience –of us the audiences staring at the screen silently for 7 minutes, to witness the every day miracle of sun coming up, realizing the smallness of human existence has been one of the most thrilling experience in the cinema of all time for me.

It's only been the last couple of years that I've been writing about films seriously, realizing that film medium can go much further than just mere entertainment and that freedom from the dominant narrative structure can be exhilarating. Attending Art of the Real series showcasing non-narrative films at Film at Lincoln Center was an eyeopener for me because it exposed me to a current crop of shape-shifting postmodern cinema, which subverts the medium’s traditional narrative structure and characterization and tests the audience’s suspension of disbelief (the works of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Miguel Gomes, José Luis-Guerrin, Lisandro Alonso and others), enticed me and pulled me into the very depth of the cinematic rabbit hole, and left me exhausted and confused and exhilarated at the same time. And this is where Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990) serves as a precursor for these more contemporary filmmakers. In Close-Up, he returns to the idea of an imposter of a film director: a man swindles an upper middle class family by pretending he is a famous Iranian film director, Moshen Makhmalbaf. It’s a story of a movie fanatic who admired Makhmalbaf so much he wanted to be him, but without malicious intent. The film is based on a true court case, and everyone participating in the film are real life characters reenacting their ‘roles’ in Kiarostami’s film under his direction, including the imposter, who is questioned off frame in the courtroom scenes. The result is a touching, moving examination on 'life imitating art imitating life', rather than sensationalistic satire about fame and deception.

There is no doubt Kiarostami’s success in the West has brought a spotlight to the Iranian cinema on the international stage and drawn attention to a second generation of Iranian New Wave with directors, such as Jafar Panahi, Majid Majidi, and Asghar Farhadi. Kiarostami’s influences are quite palpable in younger generation of Iranian directors. Panahi started out as his assistant director, and many of his films take place in a moving car. Majid Majidi’s films usually deal with children’s flight and they owe a lot to Kiarostami’s Kanun films, Where’s Friend’s Home and Life and Nothing More…. and Asghar Fahadi’s elusive narratives and unreliable heroes in About Elly and A Separation owe a lot to Kiarostami’s convention subverting cinema.

Unlike many other Iranian filmmakers who actively make political statements with their work (his former assistant Jafar Panahi being the most vocal one), many of Kiarostami's films can be seen as Iranian sociopolitical fables rather than overt political statements. But the given complexity of his work, the Iranian government has banned the exhibition of his films, fearing that there might be hidden subliminal messages. And unlike many Iranian New Wave filmmakers of his generation who fled the country after the 1979 revolution, Kiarostami stayed and kept making films exclusively in Iran. He accepted that restrictions and censorship were a part of life in a rigid theocratic society, but always had found ways to express himself in changing environs both before and after the revolution. The prime example of this would be The Report (1977). Firouzkoui (Kurosh Afsharpanah), the tax investigator, is perhaps the least likable character in all of Kiarostami's protagonists- he cheats, lies and abuses his position as a government official. After being accused of corruption and short on rent money, he resorts to beating his wife and neglecting his baby daughter. Kiarostami observes all this from a distance. Considering The Report was made before the Iranian Revolution in which the Shah wasoverthrown and The Islamic Republic established, the film is a snapshot of the state of Tehran of that era —women wearing revealing Western clothes, men drinking and gambling, gridlocks in the city streets, etc. The film is a report on petite bourgeoisie, steeped in selfishness and materialism.

Kiarostami made films exclusively in Iran until 2011. I reckon it was exactly that transcending subtle artistry that fooled the censorship for a long time. But during the conservative president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s tenure, he found practicing his craft in Iran increasingly difficult. Thankfully for us, it directly resulted in two international productions, Certified Copy (2011), set in Italy, and Like Someone in Love (2013), set in Japan. Even though the film’s settings are different and have international movie stars, his artistry hasn’t changed. His cinematic playfulness and his usual theme of perceived notion of truth and reality are there, even deepened and more sublime than before.

Juliette Binoche, an internationally renowned French actress, stars in Certified Copy. It starts out with an Englishman James (William Shimel) giving a talk on his new book about the legitimacy of copies compared originals in art in picturesque Florence. As infatuated antique dealer (Binoche) picks James up and drives him around town as a guide, the film becomes something else: deconstruction of a relationship. Even though it's the first film set outside Iran, there are Kiarostami touches everywhere- long driving shots, actors talking while looking at you straight in the eyes, blurring the lines of what's real and what's not. As the couple discuss the legitimacy of a copy of a master painting, mirroring their relationship, as we witness the copy of the real married couple breaking apart. Is it any less humanistic because we are watching a film with big movie stars? Do our emotions feel false when we watch Binoche’s character suffering? Deceptively simple, yet as much complex as Close-Up and Taste of Cherry, Certified Copy doesn’t disappoint.

Like his other films about acting and being and perceived notion of truth and reality plays heavily on Like Someone in Love. The premise of the film is pretty simple: Akiko (Rin Takanashi), a pretty young Japanese college student doubling as a call girl meets an elderly professor Takashi (Tadashi Okuno) who takes a protective role in her life. But like Kiarostami’s other films, it ends in quite a different place than where it starts. Many scenes in the film are seen through the windows and the dialog spoken off frame or on the phone. Just like the technology being a hindrance to human connections in Wind Will Carry Us, the abundance of cell phones here sets people apart. The film’s three protagonists – Akiko, Takashi and Akiko’s overjealous boyfriend Noriaki (Ryo Kase) act and behave like they don’t know how to behave in each other’s company. Yet they are more frank about their secrets with total strangers than with their own families. And there are many clues that suggest the cyclical nature of love that we can chew over for a long time. It’s a harder puzzle than usual in Kiarostami’s oeuvre and more complex. Although the film is less optimistic than his previous films, one can tell that the master filmmaker is adventurously expanding uncharted territories both physically and culturally.

Kiarostami's passing in 2016 was very unexpected. Among all the cultural luminaries who passed on recently, his death really saddened me in a very personal way. When I heard the news of 24 Frames, the film he's been working for three years and unfinished at the time of his death, was going to be released with the help of his son Ahmad, I was more than eager to see the late master's final work. The film is, in large part, a collaboration of Kiarostami and visual effects artist Ali Kamali. Based on Kiarostami's photographs and videos, Kamali was responsible for digitally creating multilayered images that (provide description here). Kiarostami's idea for 24 Frames is simple—try to bridge the gap between painting, photograph and moving pictures. That instant is frozen in time forever, but what about just before and after that moment? They are usually easily discarded from and forgotten in our memories. Cinema as we know it, can prolong that moment for a little longer, to help us in imagining the narrative, in contextualizing the content within the frame a little more. Comprised of 24 4-1/2 minute static shots, the film most resembles Five, where he held his camera to five static scenes in various length. And it's the same minimalistic approach without human presence(except for two scenes) he applies here.

In order to demonstrate the landscape frozen in time, 24 Frames’s opening frame is the famous winter landscape painting, The Hunters in the Snow, by Pieter Brueghel. Accompanied by the sound of hounds, wind, footsteps, and people playing on the frozen lake below, we see subtle animated movements - smoke billowing out of chimneys from down below, birds flying across the frame, one of the hounds coming alive and trots and pees on the tree, while certain elements stay frozen, like the hunters themselves and the pheasant flying across the sky. In this moment, Kiarostami offers us the chance to contemplate on various things—the power of our imagination, fleeting nature of time, immortality of art—.all in one frame. Kiarostami's love of nature and landscapes comes to the fore - deer, cows, various birds, dogs, horses, cats, snow, rain, wind, ocean, forests, and mountains.

Windows figure heavily in the film as well, constantly framing the frame. If it's not windows, it is fences or columns. He wrote in 2009 about his photography:

I've often noticed that we are not able to look at what we have in front of us unless it's inside a frame. (Kiarostami, Interview with Abbas Kiarostami, Guardian, 2009)

As he championed shooting from the moving car throughout his films, he uses car windows to frame images. One scene, for example, is dedicated to the snowy landscape outside the car window—a couple of horses run parallel to the moving car, we lose the sight of the horse as it lags behind. The car stops, the automatic window rolls down, the horses reappear. Now we are presented with two horses playing around in the blizzard through the car window. After a while, the car moves on. Humans are not in the frame most of the time. Kiarostami doesn’t necessarily makes a nuisance out of humans nor does he present them as a threat to nature. He seems to say that this is the life as is, with us in it. But as always the case with Kiarostami's films, 24 Frames is only deceptively simple.

One moment in the film exemplifies this complexity. It consists of a group of Iranian family looking at the Eiffel Tower from a distance, with their backs toward the audience. At first we don't know if this frame is a photograph or not. The voices from the crowd, then people working by in the foreground follow. It's another intoxicating concoction by the master: mixing the idea of 'the window to Paris' and current climate of immigration in the first world since it's hard to determine where this scene takes place.

Accompanied by Andrew Lloyd Weber's "Love Never Dies," the last 'frame' is strikingly beautiful. We are presented with a frame within a frame – of a window. A girl, back to us had fallen asleep with her headphones at her desk in her room. Her laptop is playing some unidentifiable Hollywood movie where a couple slowly kisses. We see tall trees blowing in the wind through the window. With Weber’s lyrics tell ‘love conquers all, even death”, it’s a fitting send off to the culmination of Kiarostami’s artistry. It's even more sublime than the last scene of his film Taste of Cherry that ends with Louis Armstrong's "St. James Infirmary blues". His son Ahmad did an admirable job choosing these 24 out of 30 'frames' or so Kiarostami considered using in the film.

Nothing is comparable to his artistry. As Asghar Fahadi told me last year about his death:

This was the bitterest occurrence that happened in the cinema past year, because he was one and only. There is no one like him. Many people tried to be like him or copy him but because their personalities are different from his, their films didn’t come out the way his films did. (Chang, Interview: Asghar Fahadi on His New Film Salesman, Screen Anarchy, 2017)

Kiarostami was a true polymath. For those who are familiar with his artistry - his haiku inspired poetry, his minimalist landscape photography as well as his enigmatic films, 24 Frames represents the culmination of all his artistic practices. What make it so sad to me at least, is that there is no finality to the film. It's as if it can go on forever, completely consistent with what he had been doing all his artistic life. 24 Frames is a great testament to his being as an artist and as a person.

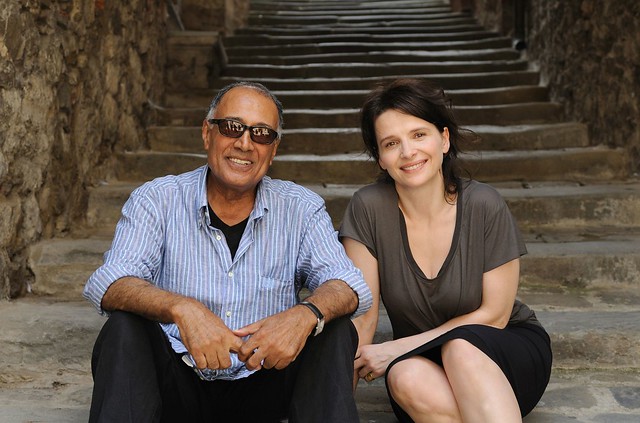

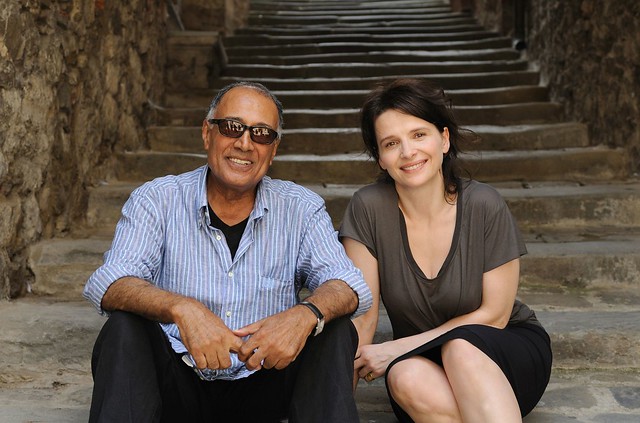

I had an honor and pleasure to interview Abbas Kiarostami in 2013 when his film Like Someone in Love played at the New York Film Festival. As expected, he was the warmest, wisest, humblest, most thoughtful artist I've ever encountered in my short career as a film critic. This was his answer when asked about the universality of his films:

I think it's a lifetime practice, or habit or way of seeing things. I remember for a long time as a young man I wouldn't take what I see on TV for granted. I would never accept generalizing 'that's how Americans are,' or 'that's how Japanese are.' I was always much more interested in individuals rather than a culture or a country in general sense. This collective judgment or agreement on certain culture has always annoyed me. I deeply believe, excluding ideological positions, that we are the same. In details we can have our differences but in the main aspects of our lives -- our sufferings, joy and pain -- no matter if we are Japanese, American or Iranian, we are the same human beings. So if you have this as the principle of life and relationship, then it shows in your work.

When I think about Kiarostami’s films, it’s not his style that strikes me the most. I think of his search for genuine human connections within the film medium, both among his characters and us the audiences and him the filmmaker. I think of his effortlessness in doing so. I think of his generosity and warmth when I got to meet him. As one critic said, postmodern need not mean post-human (Ebri, Post Modern Need Not Mean Post-Human: Abbas Kiarostami and the Paradox of Cinema, Village Voice, 2016). Everything he pursued in his paintings, poems, photographs, films, he found common ground in us as humans. Instead of spoon-feeding us in a didactic manner, the open-endedness of his work made us contemplate on our childhood, fleeting human life and the nature of reality. It’s that participatory aspect of his work I respond to the most and appreciate. He was really one of a kind. And I will miss him greatly.

….

Works Cited

Kiarostami, Abbas. Beard, Michael. (Translator)“Walking with the Wind” Harvard

University press, February 28, 2002

Chang, Dustin. “We Are All The Same: Abbas Kiarostami Interview.”

Screenanarchy.com, 14 Feb. 2013, https://screenanarchy.com/2013/02/abbaskiarostami-

interview.html

Chang, Dustin. “Interview: Asghar Farhadi on His New Film, THE SALESMAN.”

Screenanarchy.com, 25, Jan.2017,

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. “ABBAS KIAROSTAMI: A Dialogue Between the Authors

(Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa & Jonathan Rosenbaum).” Jonathan Rosenbaum.net, 7

Nov. 2001, https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2001/11/40847/

Kiarostami, Abbas. “Interview Abbas Kiarostami’s best shot.” Theguardian.net, 29 Jul.

2009, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jul/29/photography-abbaskiarostami-

best-shot

Ebert, Roger. “Taste of Cherry.” 27, Feb.1998,

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/taste-of-cherry-1998

Chang 15

Bilge Ebri, Post Modern Need Not Mean Post-Human: Abbas Kiarostami and the

Paradox of Cinema, Village Voice, 2016

Jones, Jonathan. Children of the Revolution, Guardian, 2000

Soltani, Amir. The Child Heroes of Abbas Kiarostami’s Films, Movie Mezzanine, 2016

References

Wikipedia contributors. “Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 15 Jan. 2019