After winning Grand Jury Prize at Berlin early this year, Alain Gomis's Félicité played as part of the slim but always robust Main Slate at New York Film Festival. Featuring great Véro Tshanda Beya Mputu as the title role, a single mother and a singer struggling to survive in the bustling streets of Kinshasa while trying to find love, Félicité is a structurally daring, vibrant, sensual and hopeful African film that you don't get to experience often. For me it was one of the highlights of the festival.

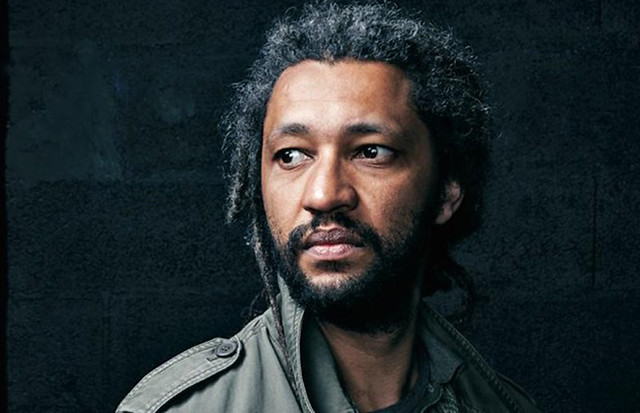

Gomis, a Senegalese director, was in town for the festival and I was lucky enough to have a chat with him about doing a film in Congo for the first time, the state of African cinema, his relationship with his generous and talented collaborators and on his method/non method- letting things take its own course. Even though suffering from a cold, Gomis was very generous and open with his answers.

And I am very happy that the film was announced Senegal's official entry for the Oscars and is getting a theatrical run here in the States starting 10/26 at Quad Cinema in NY.

The music seems to be the heart of the film. I heard that you are a big fan of The Kasai All-stars and the whole project began with them in mind. So if you can tell me about that a bit?

I’ve heard their music a few years before, introduced by a girl I know. It was through their album called Congotronics- several music groups from Kinshasa, playing the music called ‘Tradi-moderne’ in French, a mix of traditional Congolese music and modern stuff. Most of it is traditional music but the fact it’s played in the city of Kinshasa, it’s mixed with electric guitars and… they made this music that is perfect embodiment of life in a big African city. It’s really connected to cosmogony and transcendental music, so it’s steeped in tradition but mixing with the urban way of life. So it was perfect for me to start the project with this music to portray the urban African life.

With your previous films, it was Dakar and now it's Kinshasa. These cities themselves become very important characters in your films.

It’s always interesting to see the effect of the city on its people, and conversely, how they change it. How we are played by the city and how we influence it. Africa has a very small cinema industry. And there is this need for the symbiotic relationship with cinema and the society itself to present the life on the street.

Most of the time the films are coming from the outside which is a big problem because you identify yourself with the culture that is not yours. Of course it’s cool to have relationship with the rest of the world but you also need to have access to yourself. So it’s also important to me to try to portray what it’s like there. It is part of my mission in a way.

I talked with Ousmane Cisse when he was here presenting Timbuktu. And he told me how hard it was for him to finance his films. Is it the same way with you? How did the funding for Félicité come about?

It is not easy, but it’s getting better. This film if very concretely funded by Senegalese Production Fund which was set up in 2013. We had a French production company and post-production is done in Belgium. We had some Lebanese co-production too, German, Gabonese…

Wow.

So yes, we try to get money from here and there and everywhere. But the good part of it is that I had total freedom. Because if you had one financial partner, they have much more influence on you and what you are doing. (laughs) Having little here and there, you have more freedom.

It was really interesting to see the film in distinctly two parts. The first part is like a social docu-drama in terms of pacing and everything. And the second half, the tempo slows down a lot and it’s a love story between Tabu and Félicité. I liked that a lot. Is the pacing of the film connected to the music?

Yes. First I wanted to have easy entrance to the movie. I wanted to have a simple drama structure for everybody to be able to get into it easily. And then coming in to the heart of the movie which is Félicité’s journey of falling flat on her face then coming back up. But that part of the film is not something to tell but something to live, something to experience.

So yes, its inspired by musical structure. I think that’s the relationship that I have with music and I assume everybody else too. You listen to music and you start to cry and you don’t know why. Just like a concert, like a space between the stage and the listeners, I wanted to build a relationship between the screen and the audience.

I really appreciate the handheld photography by the great Celine Bozon in the streets of Kinshasa. How was the working relationship with her?

It was a first time working with her for me. It was like love at first sight! It was an incredible relationship. She was so devoted to the film and the filmmaking. She has no fear. She is completely into creating sensations I was looking for.

It was also my first time having relationship through books. Just last week, she sent me this book and I was reading it on the plane on the way here. It’s a book about the art of archery. This relationship is like not to interfere with your sensation with your gesture in a way. We’d have incredible conversations – not about the frame or contrast, just trying to be more direct as possible. She suggested using the headphones, so she had a headphone set and I had a microphone. We had dialog during the takes, to find a good angle or sometime she would be just proposing something and I just try to say few words and she answers. sometimes it would be contrary…. The film was a true collaboration.

We have built a crew to shoot on the streets and interact with people. So we come several weeks before, talking to people. Some of them became part of the crew also while shooting. We had no boundaries. Someone was getting in the frame and it was possible. It wasn't like a traditional 'film set'.

Somewhere you mentioned that you were influenced by Yasujiro ozu. Can you elaborate on that?

I remember I was watching this film, it was a shock. I can't remember the English title of it.... It was... I Was Born But... Taking place in Tokyo about these two kids. The thing is, these kids were really me. They are trying to fit in their new surroundings, trying to fit in. I especially loved the relationship between them and their fathers. It was really shocking to me because it was an old film, black and white and a silent film at that. But it was me! That’s what cinema is for me. You can find that intimacy in a film that is made long ago on the otherside of the world. Cinema is creating that common space. The film really had a big influence on me.

I can see that in your films. Just watched Aujourd'hui. It’s very contemplative and very quiet, compared with other contemporary African cinema I’ve seen. You have a very distinctive style and approach. You possess this quiet sensitivity I admire.

Thank you.

How did you find the main actress, Véro Tshanda Beya Mputu?

She came in the audition. I’ve seen a lot of actors in theater and other auditions and so on. But this was an open casting- it was open to everybody. She came to it by chance because her friend told her to try it. She came in and I see her and I had the character in mind and she was quite different from Félicité I imagined. So OK, 'let’s try her in the part of the nurse', I thought. But she was so powerful in her performance and presence. So concrete, even when she remain silent, she had this energy that kept going through her. So I asked her to come back.

So we had these interactions for 6 months, I wanted her to come back and forth and we continued to build a character together during that time. At the end, I had to accept her as the character which meant I had to follow her. All these things- Vero, the language I didn’t speak, the fact that I didn’t know Kinshasa- what I had to do was to…just let the film happen. It was me just trying to hear, not dictate, not “this is the story I want to tell!” I had to accept the fact that it’s not about me.

It’s telling that the film has its own flow that I really like. It feels organic and natural to me.

Is it common to have kind of an open relationship between Tabu and Félicité in modern African city?

For sure. I mean, in this time of economic pressure, the traditional sense of family is blown. We have young girls with children and everything like that is absolutely new. The film was my interrogation on what it means to be a couple. It was about accepting the freedom of the other person and of yourself. 'What part of the freedom am I giving up to be a couple?' I wanted to show these kind of new situations in urban African life and ask the audiences what would they give up.