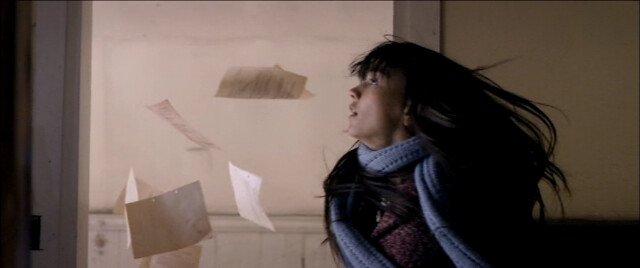

However dismal 2016 has been, I had a privilege to start the year discovering the work of a Welsh/Scottish filmmaker/artist Scott Barley. As it turns out that I also had a privilege to end and start another year with the work of Barley and conduct a second interview on his new work Sleep Has Her House. It's a monumental piece of pure cinema that is hard to describe in words. It was a visceral, immersive experience that I will never forget. Many of the questions I put on Barley here are about "how", since I know a bit of his background and his objectives from the last conversation we had, and mostly because the technician in me was wowed by his craft in SHHH. I was so genuinely invested in the experience, some of my questions came across as naive in hindsight. No matter.

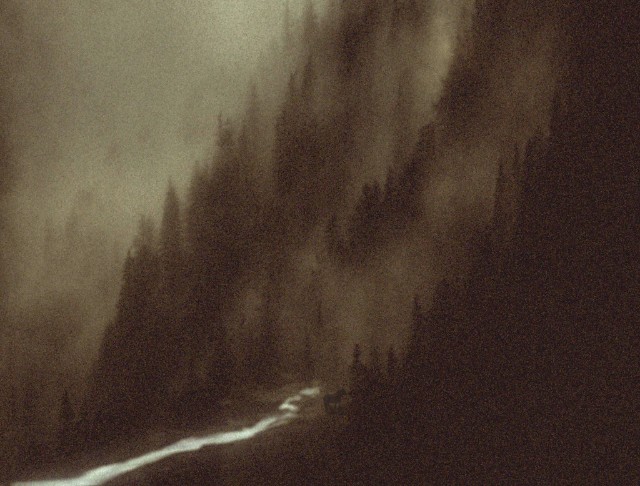

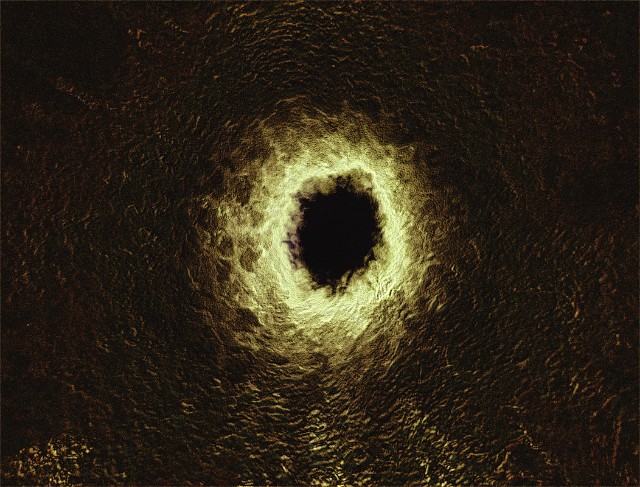

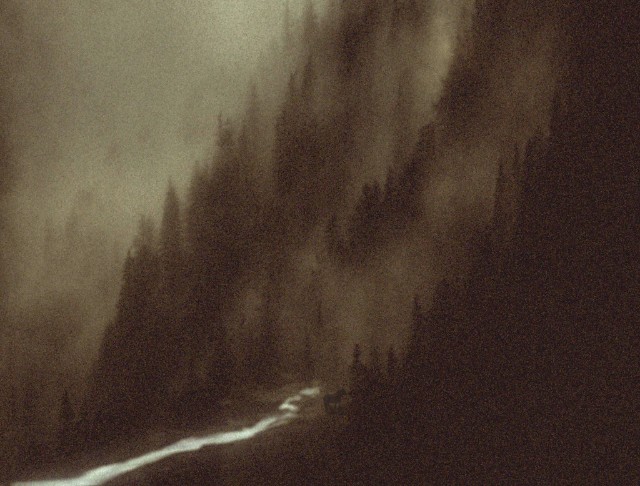

Here is without further ado, my second interview with Scott Barley, accompanied by stills from Sleep Has Her House, courtesy of the filmmaker.

The texts in the beginning that starts with “The shadows of screams climb beyond the hills…” Can you tell me the origin of that poem?

Despite not consciously thinking of it at the time that I wrote the opening, I think that Thomas Pynchon’s, Gravity’s Rainbow was a big influence. It’s the opening line. Ever since reading it, it has remained with me like a scar – “A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.”

I also work in a stream of consciousness way, and don’t overthink what surfaces in my mind. I go with what feels right, always.

In our previous conversation, you talked about being lost in your work and only later you understand the meaning of a particular work that you’ve done. You talked about the importance of polysemy. I am wondering if there was any difference in your approach doing Sleep Has Her House, a feature that has to sustain a greater length and structure than your previous work.

In our previous conversation, you talked about being lost in your work and only later you understand the meaning of a particular work that you’ve done. You talked about the importance of polysemy. I am wondering if there was any difference in your approach doing Sleep Has Her House, a feature that has to sustain a greater length and structure than your previous work.

I was conscious of that, and it frightened me for a long time whilst making the film. But it came to a point where I just decided to no longer be guided, or rather, to be anchored by this fear. Ultimately, I made Sleep Has Her House exactly the same way as I have made my previous, shorter works. I feel my way in the dark. I feel what feels right, and never question it, and never deviate from it. I feel, and feel alone. I love not being fully in control when making. I want the film itself to have its own autonomy as it is being made, and for it to always be a few steps ahead of me. I want it to give birth to itself. For me, making a film is largely the same as watching one. You must not resist. Once you let go, you are no longer a captive. Just let it wash over you like an ocean. Swim with it. Drown in it.

I think that my approach is more visible in Sleep Has Her House than any of my previous works, partly due to the longer running time, but also because of the stronger presence of the liminal, the mystic, and the unknown, which I feel took root with my short film, Hunter (2015), but is also there much earlier, in works like Nightwalk (2013) for example. All I am doing is going deeper, darker, and narrower.

Guessing from your images, those locations in Scotland you filmed have otherworldly beauty. What is your relationship as an artist with these places?

Guessing from your images, those locations in Scotland you filmed have otherworldly beauty. What is your relationship as an artist with these places?

My heart is, and always has been in the Highlands. I have family there, and it’s where I feel most at home of any where I have been. Working in these landscapes and tenebrousness is a way of articulating and sharing my biophilia and nyctophilia. It’s also about sharing an aloneness with others. As Nathaniel Dorsky said, ”Sharing aloneness with other people is a great answer to loneliness.”

We must remember the difference. And in another sense, it’s about re-establishing a relationship with what we as a species have lost; what we have ignored, taken for granted, or destroyed, and how our attempts to control nature is a folly. We are guests in Her house.

How many days and nights have you spent filming up there? Do you usually travel and film alone?

How many days and nights have you spent filming up there? Do you usually travel and film alone?

For Sleep Has Has Her House, it was shot over the course of 4 separate days throughout 2015 and 2016; one day in the Brecon Beacons of Wales, and 3 days of traveling around West Scotland, with around 16 months of post-production in between. It seems ridiculous, seeing that in print, but that's how it goes.

I have traveled with others on occasion, but I always work alone, apart from some university projects, where having a crew was mandatory, i.e. Shadows (2015), Ille Lacrimas (2014). I am not against working with others, but as my work becomes more personal, I have found that my own process which I have developed does not easily permit communication and collaboration with others, as I don’t always know myself why I choose to do something a certain way. As I said before, I always go with my feeling, and trust that. I traveled with a friend and colleague whilst shooting some of Sleep Has Her House, but I worked completely alone. Every part of the process, whether that is concept, shooting, editing, or sound-design is performed by me alone. I think filmmaking, genuine art-making, regardless of whether you're working alone or with a crew is always a solitary endeavour – you are pouring your soul into something. It can be lonesome. And it can hurt.

As Emil Cioran said, ”Write books only if you are going to say in them the things you would never dare confide to anyone.” The same applies to filmmaking. And I would add, you put into your work what you would never even dare to confide to oneself, or even wish to understand. It is not a reveal, or a "pouring" of logic, it is nothing but a deluge of pure, unadulterated feeling; feeling alone. And pure feeling cannot and should not be translated into rational thought.

I am astonished by the fact that it was all shot on iPhone. Can you tell me the process from capturing those images and how it morphs into the final piece?

I am astonished by the fact that it was all shot on iPhone. Can you tell me the process from capturing those images and how it morphs into the final piece?

Firstly, I should probably mention that I always begin a film almost like one would keep a diary. I have no idea, or agenda to make a film. I simply document. I shoot what attracts me, random things, animals, variances in light, the water, the stars; simply what draws me in on different days, different nights, in different places. Once I have built up a body of footage, I start to see connections. These pieces of footage could be taken months or even years apart – and miles apart too. Just like in Hunter (2015) there are sequences in Sleep Has Her House which are comprised of shots filmed in two separate countries that are then invisibly stitched together. But these connections between different pieces of footage all happen organically. I never force these connections. I never force a film when it doesn’t come. The films find me – not the other way round. When they come alive and start to writhe, I simply hold on. All my films have been made this way. Some happen quicker than others. Once these connections are established, a narrative - through images - begins to germinate.

Sleep Has Her House was roughly 90% shot on my iPhone, the rest being made up of some drawings I did about 5 years ago whilst studying fine art, and some more recent DSLR footage. All of that was then superimposed together. Some shots, such as the 12 minute take of the sun setting in real-time, followed by the darkness, and finally the storm corrupting the night is comprised of nearly 60 layers of footage in 2K resolution. It took two months for that shot to render.

One mesmerizing shot after another, Sleep Has Her House is a truly hypnotic experience. But the techie in me was wondering as to how you accomplished the look of those images. For instance, those incredibly long waterfall sequences where we very slowly pull out to reveal the full extent of the landscape in the darkness. Or the scene of mist rolling over the forest and the trees change their colors.

One mesmerizing shot after another, Sleep Has Her House is a truly hypnotic experience. But the techie in me was wondering as to how you accomplished the look of those images. For instance, those incredibly long waterfall sequences where we very slowly pull out to reveal the full extent of the landscape in the darkness. Or the scene of mist rolling over the forest and the trees change their colors.

Thank you. I hope you don't mind me saying, but just like the films themselves, I think it is best to be kept in the dark. Once we objectify, once we understand – we kill.

There was one visceral moment when the rainstorm passes through and from complete darkness comes the frightening (yet beautiful) forest fire which made me jump out of my seat! Even though the film is finished and obviously you are alive to tell me that it’s done, at that moment, stupidly on my part, I was very concerned about your safety and well being. Can you tell me about that experience?

As Michael Haneke said, “Film is 24 lies per second at the service of truth, or at the service of the attempt to find the truth.”

The fire is complete fakery, something that I composited, but I’m very happy - from your response - that it seemed genuine.

What do you think about in the middle of the night alone in the forest?

What do you think about in the middle of the night alone in the forest?

I think about the weight of the dark. Rather, I feel it. The heaviness. Sometimes you can feel the heaviness of the night. The dark - on different nights - has different colours. I feel its heaviness most when it is red or green. I do not mean that the colour of the night is red, or green, but I feel a colour around me. It absorbs me. It goes from the air into my core. Sometimes, the night has a hunger. It devours everything. In these moments, everything is unknown to me again. I listen. I hear. I feel the air. I feel the earth. The only thing I know is the earth under my feet. Everything is elsewhere. I am a child. I think about the same things that I try to show in my films. I think about all the things that are beyond me. I sense things dancing within the dark, out of reach. They disarm us. They seduce us.

I remain quiet. I remain still. Sometimes, I close my eyes, and I try to dance with them.

Sleep Has Her House has world premiere on streaming flatform, Tao Films, please visit

their website

My 1st interview with Barley in February 2016