Regarded by many as the best contemporary Japanese filmmaker and spiritual heir to the master filmmaker and humanist, Ozu Yasujiro, Kore-eda Hirokazu has been making quiet, deeply affecting films about childhood, family and death. I told myself not to cry while watching his new film Like Father, Like Son at the New York Festival last fall, but couldn't help tearing up at the end.

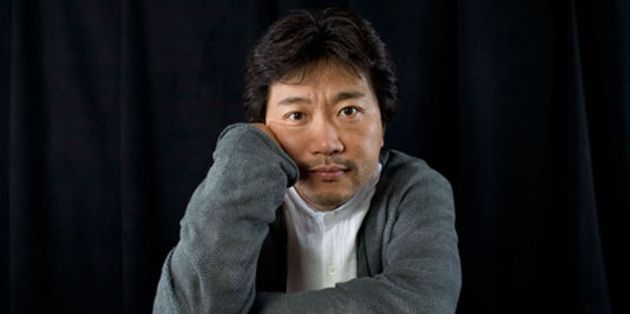

Soft spoken and a with gentle demeanor, Kore-eda was exactly how I imagined him to be when I sat down for an interview, one early October morning.

Many of your films deal with family and childhood and this film is no exception. I'd like to know about the origins of this particular film which involves a 'switched at birth' story.

For the last couple of films I tried to incorporate my life in it as much as possible. I tried to incorporate motifs and things from my life, the subjects that are close to me. In terms of this movie I think the starting point was what happened with my daughter. I actually didn't have very much time to spend with her. While working on my last film, I Wish, I was away for about a month and when I came home after being away for that duration, she recognized me as a father but I could see that there is this 'resetting' in her mind as to who I was. She was three at the time. Then when I was leaving the next day, in the hallway to say good bye, she said, "Please, come again." [laughs]

It was shocking to me. Then it came to me that even though we are connected by blood, a father has a very different existence and relationship, compared to that of a mother to a child. So I actually panicked. I thought, "this is not good." And based on that experience it made me to think about the ties between the parents and the children. Especially time. The time we spend together, compared to just blood ties - all these went into making this film.

So then do you feel closer to Ryota (played by Japanese TV and pop star, Fukuyama Masaharu) more so than Ryudai (Franky Lily)?

That's right. Ryota. And making him the main character, I thought about 'who would be the least appealing character in terms of who you want to raise your child with. And that was the type I'd like the least.

Fukuyama Masaharu, who plays Ryota is a big star in Japan. Did you have him in mind for the role?

I wasn't conscious about him playing the role when I was working on the screenplay. It was Fukuyama who approached me and wanted to work together. This offer from him was the starting point. I thought I'd portray him in a different way than the way he is usually portrayed before. So that was how it happened.

I couldn't help wondering about your method working with child actors. In films like Nobody Knows, I Wish and now Like Father, Like Son, you capture the moments of pure delight in their faces that is too real to be just them acting and being in characters.

It actually starts with an audition process, forming communication with them to see whether they understand what I'm saying and I understand what they are saying- that's where it all starts. Once that communication is formed with the premise (of the film) then we move audition into rehearsals. It's not that I'll pass out the scripts to them or give them lines to say. It's more of doing a particular scene with me or a person who's going to play the father and just to see how to say the words, have them hear through their ears and have them come out of their own. It's a natural process. Out of hundred children, there are maybe five or six who I'll be able to interact in this way, with those I'll bring them to the set. In terms of the lines, I don't feed them lines, I try to incorporate their words and vocabularies into the lines I create. So i consider myself sort of borrowing their words and returning them. They are the inspiration of those lines. I might say something like, 'try to say something like you did last time or say what you told me the other day'. That's how I've been working with children the last ten years or so.

Has the Great Eastern Earthquake that hit Japan and The Fukushima disaster which has been going on since then changed anything for you as a filmmaker?

Yes, it is something that I am conscious of. It's not really about something that has affected how I express myself. That's something I don't really know for sure. There's probably a portion which unconsciously incorporated into my work, but it's not really simple. Of course there are a lot of works regarding the subject and it's important. But I really think that we are not going to be able to digest everything that's happened until, maybe 5 or 10 years down the road, in terms of its impact on Japanese society.

[He pauses for a long time, then continues]

But I think this time, in terms of making this film, there were couple of motivations for it. One was definitely had to be the earthquake. I think it really enforced the idea of bonds in Japan. The idea actually became very trendy. In a way, it wasn't so good in Japan before (in that regard). But the idea of bonds and people supporting each other and all of Japan becoming one has become very common in Japan. I've been thinking about that, about how we can reduce that feeling to a small community that is family. So I think in terms of how I came up with the idea for the movie about a man and his bond with his family, I suppose the earthquake played the role.

There is always a sense of optimism I feel in your movies. Is it your inherent nature as a filmmaker to portray childhood or the next generation in optimistic light? Is it why you always go back to the subject of family?

In Japan, the word optimism doesn't have a positive connotation. It has a tinge of 'escape from reality'. I wouldn't use the word to describe my work. I don't like making films about downcast or pessimistic side of life. That's just not what I do. The thing about making movies about family is that it is a troublesome subject but also essential. Something that you need.

I know that you support the younger generation of filmmakers by producing their films. Nishikawa Miwa (Dear Doctor, Dreams for Sale) is one of them. I'm just wondering how you go about supporting certain projects with younger directors. And can you tell us some young directors you can think of that we need to know about?

Some of them I supported have already been in my crew so there is a connection already there. And when I actually read a script by someone and it seems interesting, I'd support them. That's usually the process. It may not be so in the film world, but in the Japanese TV community where I came from, it is pretty common practice to help younger pupils. And also I don't have any director friends, so it's a good way for me to make friends who are directors. [laughs] Young directors, young directors….

[Thinking really hard… asking others]

Yamashita Nobuhiro (Linda, Linda, Linda) and Nishikawa Miwa, come to think of it they are not that young. they are all in their forties. [we all laugh] Right now, they are the two I can think of…

No comments:

Post a Comment