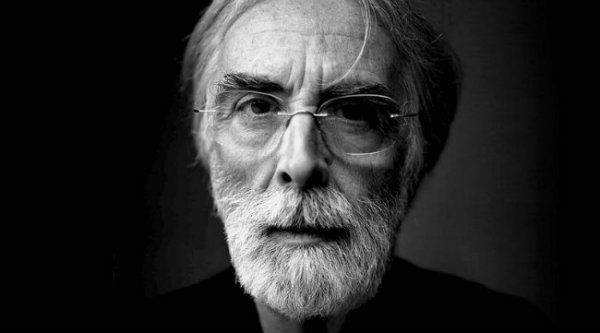

Austrian film director Michael Haneke took home the coveted Palme d'Or at Cannes for the second time after his The White Ribbon in 2009 and swept the year end European film awards with his austere, devastating film Amour. I got a chance to attend a roundtable interview with the director at this year's New York Film Fest. As the interview unfolded in the Executive Room at the Trump International Hotel where myself and six other journalists were served with 'Donald Trump approved bottled water', my expectations were met -- Haneke outright avoided many pointed questions we asked and when he did answer, they were very concise and to the point. But also, there was a lot of laughter to be found in the room. This mild mannered, white bearded old man could be anyone's grandfather, I thought, temporarily suspending the truth that this is the director responsible for Funny Games and The Piano Teacher. But in his answers, I found that his films are not so cut and dry as they often appear to be.

Q: Amour is being called as a very humanist film. I don't argue with that. But I feel there is something more at work here. I feel that the film is pushing the audience to an end point that there is no option but to condone the unconscionable act. Was that your goal, if so where did that desire comes from?

Austrian film director Michael Haneke took home the coveted Palme d'Or at Cannes for the second time after his The White Ribbon in 2009 and swept the year end European film awards with his austere, devastating film Amour. I got a chance to attend a roundtable interview with the director at this year's New York Film Fest. As the interview unfolded in the Executive Room at the Trump International Hotel where myself and six other journalists were served with 'Donald Trump approved bottled water', my expectations were met -- Haneke outright avoided many pointed questions we asked and when he did answer, they were very concise and to the point. But also, there was a lot of laughter to be found in the room. This mild mannered, white bearded old man could be anyone's grandfather, I thought, temporarily suspending the truth that this is the director responsible for Funny Games and The Piano Teacher. But in his answers, I found that his films are not so cut and dry as they often appear to be.

Q: Amour is being called as a very humanist film. I don't argue with that. But I feel there is something more at work here. I feel that the film is pushing the audience to an end point that there is no option but to condone the unconscionable act. Was that your goal, if so where did that desire comes from?

A: That's not my impression at all. My impression is that I'm not trying to condone what I'm showing. I'm trying to present the film in its entirety. This film and that scene in particular, is presented in such a way that it's open to a number of interpretations.

The title of the film is very simple, yet provokingly so. I've heard that it was not your first choice. Why did you go with it?

I chose the title because I couldn't come up with a better one. I had a list of about 20 titles. None of them I was satisfied with. I was having lunch with Jean-Louis (Trintignant) and I read him the list of titles. And Jean-Louis said, the film is about Love, why don't you just call it that? I thought that was a very convincing argument. If I were making a conventional love story I would've never chosen that title because it would've been too obvious.

For Trintignant it must've been very personal approach since he starred in A Man and a Woman and its sequel twenty years later and now Amour, almost 50 years later. Did you talk about this symbolism with him?

You have to ask him about that. We never talked about it. I'm not a fan of

A Man and a Woman.

What was the effect on shooting with Emmanuelle Riva ? You take her to a place where even in films that are that are supposedly looking at the subject, most films usually turn away before you do. Considering the amount of time and her coming back day after day to this role, what was the impact on her?

You have to ask her that. I can't answer that. (everyone laughs). From some of the interviews I've heard of her talking about the film, she had said that it was a pleasure working on this film.

Did you lipserve anything during the filming?

One scene was very difficult for her. Because she was scared to death of that electric wheelchair, the one with the control stick. After we completed shooting for the day, we spent two evenings getting used to the wheelchair. In fact, I had to learn it before she did so I could show her and reassure her that it wasn't that difficult.

Did you do any preparations and research for the film? If so, how extensive were they?

Yes of course. It was a personal story that motivated me to deal with this theme. I have nothing to do with what you see on the screen. So it was necessary for me to do a lot of research. For that I went to hospitals and spent time in old age homes and talked with doctors. I also sat in on number of speech therapy sessions for the stroke victims where they regain their speech. Emmanuelle didn't want to do a research herself and asked me to do it for her and show her what she had to do. She had that trust in me and that's how it worked. I felt that it was important that we have that precision of accuracy in the film.

You started the film with what could be called a 'happy ending' to just reveal everything in the very beginning and the whole film is kind of a continuous flashback. I understand that it was a crucially important structural decision you made. Is it because in order to eliminate any kind of suspense for the viewer?

Yes.

Can you elaborate on that?

No. (everyone laughs)

As you said, I wanted to eliminate any kind of false suspense. It is quite clear quickly in the story how it might be the only possible ending. But what interested me was not how the film ended but rather the events that lead up to it.

What interested me was not the death per se, but how to cope with the suffering of a loved one.

I've read something about the film being advisory for young couples. The quote is, "the film should be shown to any young couples who are considering getting married and committing their life together."

Who said that?

I read it in one of the reviews.

Oh good, that means that it will have larger audience. (laughs)

Many of your films takes place in France and in French. I was wondering where your love of France comes from?

When I was going to school I studied French rather than English. Sorry if I studied English I would be speaking directly to you now. Back when I was at your age, France was the core attraction for young intellectuals, the object of our desire. It was the age of existentialism and Nouvelle Vague. Now everyone's looking to America. But it was a matter of chance collaboration that brought me to France. Juliette Binoche had seen my Austrian films and called me up and suggested to work together and that lead to our first project (

Code Unknown) and the collaboration worked very well since then.

I have a related question about language. When you write a script, do you write it in French or German then translate it?

No I can only write in German. Ever since I started making films in French, I've worked with the same translator. He does the first draft of translation and we revise it together. My French is not good enough to judge in a dialog that that's what I'm looking for.

When you write a script, do you have certain actors in mind?

It is the case for this film. I wrote a script with Trintignant in mind. Similarly, I've done this for certain German or Austrian actors in the past. It's more efficient means of writing a script because you are able to write into the scripts when you know who (the character) it is. But that's not always possible.

In the case of

The White Ribbon, I've written the part of Pastor for Ulich Mühe, one of my favorite actors who played a lead in several of my other films and you may also know him as the lead in

The Lives of Others. Unfortunately he died before I made the film, but I never gave up the challenge to replace him. However I was lucky enough to (the role eventually went to veteran theater actor Burghart Klaußner). So you never know.

Do you think if the story was told in America would it be differerent?

I've never really thought about it because from the very beginning, I wanted to work with Jean-Louis. So right now I can't come up with any American actors who would be able to play the part, certainly not the ones who exude such warmth as he does.

Did you choose to set the majority of the film in the apartment to illustrate the confines of their lives?

Yes. When you are elderly or infirmed, then your life is restricted to the four walls that you live in. That was the external reasons for the choice. In terms of aesthetic reasons for the choice, it occurred to me that when you are dealing with such serious theme as this, you have to find a fitting place like a stage. That's why I went back to a form of classical theater- real time based action seemed appropriate for the reduction of their lives.

Did you attempt to shoot this film in sequence given the limited setting and if not how did you take your actors through the extreme states that they had to go through?

We sought as far as possible to shoot the film chronologically. The one exception was the nightmare sequence, which we left for the end. But we had to tear down the sets and rebuild them. On the second half of the shooting, we had to make changes because Jean-Louis had broken his hand and we couldn't show it in certain scenes because of the scheduling issues.

You do a lot of long takes. I think it's good because it adds depth to the real old couple's rhythm of life. It's very slow and stretched out. But also I was wondering if you sometimes decide not to use long takes, cutting them before the audience to see what you'd like to avoid, for example, the mirror scene or the toilet of this ill woman whose body is unresponsive.

(Immediately after translator has finished translating the question)Yes. (laughter from everyone)

That's cruel. (another round of laughter)

Since the fate of the female character is predetermined as revealed in the opening sequence, and therefore the suspense is gone. I couldn't help focusing on the pigeons. At the press conference after the screening that you said it's up to the viewers to decide the symbolism of the pigeons. The guy next to me joked that if it was the early stages of your career, the pigeons would have been killed. The message is that now you are not into torture and cruelty, but more humane and mild. (again, laughter from everyone)

I'm OK with every interpretation anyway. As long as the film drives many interpretations out from audience, I'm open to them. Perhaps the revision of it will change in my next film.

Is there a script for the next film?

Not yet.

Can you describe an idea for us?

Not at the moment.

If you are OK with whatever the audience takes away from it--

It has to be OK. (laughs) Sorry. Go on.

However, they approach you to get you to endorse their view, say in favor of euthanasia, are you willing to sign on for that?

That's not my task.

If you are writing a film like this in sort of questions rather than themes, like how I deal with the suffering of a loved one rather than death, was there something sparked in your personal life to pursue this?

Yes there was. But I don't want to talk about it. It was a private, personal experience.

Could you talk about the music or the theme of the music in your films? I've noticed that you seem to be drawn to musicians or characters who are musicians. In fact, the characters in Amour are both music teachers. I'm wondering if you know how to play any instrument or trained as a musician.

When I was a young man, it was my dream to becoming a musician. If it had been up to me, if I was up there when the talents were bestowed, then I would've liked to have been a musician instead of a director. I would have liked to be a conductor or composer. My stepfather who himself was a conductor and a composer warned me that I was only a mediocre pianist. That stirred me away from becoming a musician. And I count myself lucky to have become a director because there is nothing more depressing that a mediocre concert pianist.

Nevertheless I've maintained my love of music and always enjoyed whenever possible to use it in my films when the occasion arises. But I don't use it the same way as how it's usually done in mainstream cinema where it's applied to cover up the directorial sins and weakness. I love music too greatly to use it for those reasons.

Do you think then other filmmakers use music as crutch?

I don't think so. I'm sure of it. (laughs)

Why do you say that?

It really depends on what kind of films. If it's a genre film, say Spaghetti Westerns, you can separate them with the music of Ennio Morricone. The music in those kind of films has a fiction in them. I have nothing against musicals or genre films for example: films of Fred Estaire or films of Hitchcock. Without Herrman, there would be no Hitchcock. But those aren't realistic films. But for most of the films, the music is there to fill the emotions there otherwise lacking. Most films claim to be realistic. I understand if there is a musician present or radio playing in the scene, but find it problematic to make up for lack of tension or emotions the director failed to create.

The pianist in the film is the real concert pianist (Alexandre Tharaud) isn't he? How did you get him involved? Did you just discover his music?

We did auditions for pianists and actors. And he was the best actor who was also a pianist among them.

As a writer/director with a definite vision, do you find that you are very demanding of your actors or do you have a lot of trust in them?

Both. I have a lot of trust in my actors and I expect a great deal from them.

In this country, it's really hard to have a rational, mature conversation about assisted suicide. There was a case recently in Britain where the High Court struck down the case of Tony Nicklinson, a former athlete who had been suffering from lock-in syndrome and his right to end his own life. I wonder if it's any different in Europe to have a mature discussion about keeping one's austerity and dignity in euthanasia cases.

You'd have to ask someone who are more knowledgeable than I am about that.

Were you at all concerned about avoiding making this film about assisted suicide?

As I said, I wasn't making a film about assisted suicide, I was making a film about how one copes with the death of a loved one. There are any number of related tangential issues and themes that are touched upon because of that question. But I never set out to deal with these themes. That is never my approach. My starting point is always certain feelings that I experienced or witnessed or read about and that emotion leads me want to explore. It's the opposite approach of television where they deal with theme of the day or theme of the week. That's not my approach.

It's always dangerous especially politically when you decide to make a film about a certain theme. In television, you say, 'oh this theme is talked about a lot. It's a hot topic, let's make a film about it'. In Austrian film history I can only think about a handful of films that dealt with themes successfully. The results are usually quite terrible. And when I say successfully, I mean not from the box office point of view but artistic point of view.

You say political dangers. Yet many of your films you deal with topics that eventually step on some potent political landmines. Are you not afraid of doing that?

If you are a film director who is making films today and you are dealing with our contemporary reality, then you are automatically expected to talk seriously about the society you are living in. And you are automatically going to touch upon raw points which you can't cover up or alter. You can't avoid that. But the point is that you are not seeking to exploit those but sticking to what you are interested in, your vision.

In many of my films I talked about the role of the media in our society not because it seemed to be important theoretically but rather because I am part of that media landscape: it touches me and part of it angers me and that's why I want to deal with it. Theoretical films are terribly boring and well-intentioned films are even more boring.

Talking about actors. The two leads are magnificent. But Isabelle Huppert is in your film again who has a brief role as the daughter. What sets her apart from her generation of actors?

I've worked with her before and we have a great working relationship. It would be foolish to change that and use some other actors I've never worked with. I asked her for the role and she did it for a personal favor. She is used to playing the leading roles and here I was asking her for a supporting role and she accepted without a moment's hesitation.

I don't know if you might not want to answer this question but I wonder since it's such a personal film and personal subject, you might consider it to be your most personal film that you've made? And thus far, I wonder if you discussed the content of your film with your family prior to making the film and what their reaction was to it?

First of all, both of my parents are dead. And the second of all, as I said in my acceptance speech at Cannes, my wife and I promised to each other that we will do everything in our power to avoid the other person being shunned off to the old age home or hospital at the end of our lives. And that's all I have to say about the question.

Just in time for Christmas, Haneke's harrowing film Amour opens in NY and LA on Dec. 19. Please visit Sony Pictures Classic's website for more information.

My Amour Review